This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tamerlane and the Jews

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book provides a general introduction to the history of Jewish life in 14th century Asia at the time of the conqueror Tamerlane (Timur). The author defines who are the Central Asian Jews, and describes the attitudes towards the Jews, and the historical consequences of this relationship with Tamerlane. Left alone to live within a stable empire, the Jews prospered under Tamerlane. In founding an empire, Tamerlane had delivered Central Asia from the last Mongols, and brought the nations of Transoxonia within the orbit of Persian civilisation. The Central Asian Jews accepted this spirit and preserved it until modern times in their language and culture.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Tamerlane and the Jews by Michael Shterenshis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Jewish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

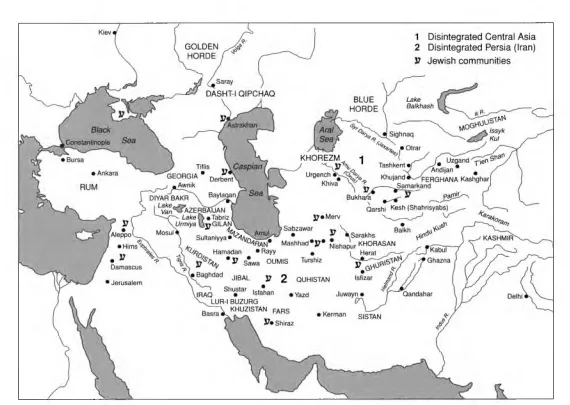

Map 1 Asia in the fourteenth century before Timur

1

THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY IN ASIA

Think, in this batter’d Caravanserai

Whose Doorways are alternate Night and Day,

How Sultan after Sultan with his Pomp

Abode his Hour or two, and went his way.

(Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, rendered into English verse by Edward Fitzgerald)

The fourteenth century is a dim, indistinct and obscure word combination for each of us who has no special historical knowledge of that period. When we read phrases like ‘it had happened in the fourteenth century’ or ‘he lived in the fourteenth century’ each of us creates a distinct and somewhat different picture about that era.

We could not do without dates but unless we are very careful, dates play tricks on us. They are apt to make history too precise. During the fourteenth century Europeans did not relate to dates in terms of BC and AD so there was no conscious notion of that century either in Europe or in Asia; in Europe the book of Joseph Justus Scaliger, Opus de emendatione temporum, a foundation of modem chronology, was only published in 1583. At the same time, the Muslim world did not live according to the Christian calendar, and dated itself by the years and centuries of the Hijra, or Mohammed’s ‘emigration’ from Mecca to Medina; the Muslim era begins in AD 622. Eastern Christians in Arab lands used the so-called ‘Greek chronology’. Following these chronologies the year of AD 1400 was the year of 803 of Hijra and the year of 1711 of the Greek Era. If we recall that Dante composed his Divina Commedia in 1307, that Petrarch was crowned a poet on the Roman Capitol in 1341, that Boccaccio wrote the Decameron in 1348, we may assume that the fourteenth century was indeed a pleasant century to have been bom into. But there is a need to be aware of the differences in human psychology of the peoples who lived then.

First of all, the people of the Middle Ages, both Europeans and Orientals, never thought of themselves as free-born citizens, who could come and go at will and shape their fate according to their ability, energy or luck. On the contrary, they considered themselves part of the general scheme of things, which included emperors and serfs, popes and heretics, sultans and dervishes, heroes and swashbucklers, rich men, poor men, beggar men and thieves. They accepted this divine ordinance and asked no questions. The exceptions were some solitary philosophers such as Jean Buridan (1300–58). In this, of course, medieval people differed radically from modem people, who accept nothing and who are forever trying to improve their own personal financial and political situation.

To the average man and woman of the fourteenth century, whether Christian, Muslim, or Jew, the world hereafter – a Heaven of wonderful delights and a Hell of brimstone and suffering – meant something more than just empty words or vague theological phrases. They accepted this as reality and the medieval dervishes and knights spent the greater part of their lives in preparation for it.

Contemporary people regard a noble death after a well-spent life with the quiet calm of the ancient Greeks and Romans. After three score years of work and effort, we go to sleep with the feeling that all will be well. But during the Middle Ages, the King of Terrors with his grinning skull and rattling bones was man’s steady companion. He woke his victims up to terrible tunes on his scratchy fiddle, he sat down with them at dinner, he smiled at them from behind trees and shrubs when they took a girl out for a walk. If you had heard nothing but hair-raising yams about cemeteries, coffins and fearful diseases when you were very young, instead of having listened to the fairy stories of Andersen and Grimm, you, too, would have lived all your days in dread of the final hour and the gruesome Day of Judgement.

Alas, the fourteenth century contributed heavily to peoples’ fears. In 1299 pestilence struck Persia and thousands died. In 1316 England and Ireland were devastated by pestilence. In 1332 the bubonic plague erupted in India. Due to the limited contact between Asia and Europe there was little trade and tourism to the Orient and for the next fifteen years the plague was confined within Asia. We have no precise figures of the human loss in Asia but in China alone millions were said to have died. The Black Death finally devastated Europe in 1347 and by 1349 a third of the population had been killed in England. This Black Death became history’s greatest disaster with an estimated seventy-five million dead. After that, repeated outbreaks of plague decimated Egypt, the British Isles, Persia and France from 1358 to 1370. Finally, from 1382 to 1385 the pestilence called the ‘Fourth’ gripped Ireland and once again thousands died.

Sometimes, fear of the future filled peoples’ souls with humility and piety, but more often it influenced them in opposite ways and made them cruel, unsentimental and overtly religious. First, they would murder all the Jews in a ghetto, or all the women and children of a captured city, then they would devoutly march to a holy spot – it did not matter if it were a Christian church or Muslim mazar – and with their hand gory with the blood of innocent victims, they would pray that the merciful heaven or Allah forgive them their sins.

In general, fourteenth-century Europe was in a bad state both politically and economically. The crusaders’ zest had dispersed a hundred years previously and the great wanderlust was still a hundred years ahead. Russia was in a bad state too. Divided into several small principalities, which were under either Mongol or Lithuanian domination, Russia was still at the very beginning of her future centralisation. From the time when the long-lasting Christian-Muslim West-East controversy began, the overland route to the profitable Orient was gradually being closed. For several centuries following the great Arab conquest, a permanent state of war existed between the two cultures. However, the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries helped to partially overcome these sad circumstances.

Asia, during the same period, was better off. It was richer than Europe, had bigger states, and more goods to offer. Also, all three major powers of the Orient of that time, the Mamluks of Egypt, the Ottoman Turks and the Mongols, were much stronger militarily than the European states.

Marco Polo is usually mentioned as the first European to have visited Asia, but there had been others before him. As so often happens in the realm of geography, it was another war rather than peace that widened Europe’s knowledge of the Asiatic map. Although historians have generally regarded the Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century into Central Asia and countries further west as an unmitigated disaster, it may also be seen as having been partially beneficial. The Mongol armies may have been motivated solely by lust for conquest and destruction, but out of this evil sprang a positive development when they rent asunder the veil which had for so long shut off Central Asia, Persia and other Islamic countries from the West. A result of the Mongol invasion was the establishment of new contacts between the East and the West, which were slow at first and encumbered with all the handicaps of ignorance on both sides.

The Eastern traveller was said to have left home and gone on the road for religious, political and (or) commercial reasons, or just to quench his thirst for adventure. The same held true for the Western traveller. The horror that was created in Europe by the Mongol conquest and attacks on Eastern Europe in the middle of the thirteenth century led the Pope and the kings of France and England, to send missionaries and emissaries to the court of the Great Khan. They hoped to put an end to the Mongols’ aggression in Europe, of converting them to Christianity, and establishing trade routes between the East and the West. Thus, in 1245 Pope Innocent IV sent a delegation headed by a Franciscan friar, John Pian de Carpini, to the Great Khan. A few years later another friar-traveller, William of Rubruck, was sent out as the representative of Louis IX, King of France.1 Yet these friars were not the first Europeans to visit Central and Middle Asia in the Middle Ages. The Jewish merchant, Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, whose period of travels extended from AD 1160 to 73 also visited about 300 different cities in Europe, Asia and Northern Africa. His diary, written in Hebrew, was edited after his death and given an introduction by Eliezer Gershon. However, it was first printed only in 1543 in Istanbul, entitled Massaot shel Rabbi Binjamin.2

Within a very short period of time, Benjamin of Tudela was followed by Rabbi Petachia of Ratisbon who, like his predecessor, was a highly motivated merchant and who visited his Jewish brothers living in other parts of the world in order to acquaint himself with their condition. His objective was to write down what he saw and heard in order to inform his people, the house of Israel.3

After Carpini and Rubruck, the Latin mission, which had started in the late thirteenth century, continued to head toward the East until the mid-fourteenth century.4 But ‘although the best travel books belonging to this period were written by missionaries, the real impetus to travel was the lure of trade, and the most frequent journeys to Persia, India and Cathay were made by merchants’.5 The greatest of them all was Marco Polo, whose two journeys through Persia and Central Asia, occurred between the years 1271 and 1294.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century all these expeditions finally made Europe ‘Asia-conscious’. The East was no longer a closed book to the West, but as yet was still an unknown quantity. It must be borne in mind when studying the medieval history of Asia that the ‘traffic’ was not merely from West to East; there were also travellers in the opposite direction, including Jewish merchants. On the whole, a good deal less has been heard of these visitors from the Orient partly because they were fewer in number, and partly because their accounts did not, in the majority of cases, become widely known, if at all, in Europe.

Often the background or interest of a traveller differed from the purpose of travel, or the travel itself was of a multipurpose nature. Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela provides the best example; his primary object was to visit the synagogues of the principal cities through which he passed, and to describe the number and condition of the Jews whom he found in them.6 As a merchant he was interested in acquiring commercial information. On the other hand, the friars who were sent to Inner Asia in the Middle Ages, besides having missionary purposes, were also bearers of political messages or acted as emissaries sent to establish trade relationships. This combination and diversity of purposes and interests widened the scope of information gathered by the travellers.

Visitors who came to Central Asia on religious missions or those with religious backgrounds, focused more on the spiritual beliefs of the people, searching for similarities and differences between Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Sometimes Buddhism, Shamanism and Zoroastrianism were also taken into account. These travellers were more interested in assessing facts about the religious minorities of the country, how they lived, population statistics, areas of concentration, their religious activity, and how all of the above affected the authorities. Alas, there are significant time gaps concerning these journeys and several periods are not covered at all.

The Middle Ages were ‘internationally minded’. Europeans of the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries rarely talked of themselves as Germans or Frenchmen or Italians. Indeed, there were several German states, French principalities and Italian independent cities. They said, ‘I am a citizen of Munich or Bordeaux or Genoa’, and belonging to one and the same church, they felt a certain bond of brotherhood.

The history of Central Asia also centred on empires and tribes, and the concept of nation and nation-state to denote triangular relationship between territory, ethno-cultural identity and political authority is very recent in this region. Indeed, Timur (Tamerlane) created an international empire but at the same time he counted himself as a descendant of the Barlas tribe.

Going back to the time of Timur, the major events of human history were moving from Europe to Asia. Europe was divided and weak. The best days of chivalry and crusading had gone. Attacked by the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt, by Ottoman Turks and by Mongols, Europe had become an armed camp by the time Timur appeared on the scene.

In his well-known book Tamerlane Harold Lamb wrote about this:

There is today near a junction of the Trans-Siberian railway a stone obelisk bearing on one side the word Europa and on the other Asia. In Tamerlane’s day this stone would have been placed some fifty degrees of longitude farther west, about in the suburbs of Venice. Europe proper would have been no more than a province of Asia. A province of barons and serfs where the cities as a rule were no more than hamlets ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Content

- List of maps and illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- A note on spelling and transliteration

- Introduction

- Prologue: legends

- PART I Historical background

- PART II The Jews and the mighty Muslim ruler

- Conclusion

- Chronological table

- Notes

- Glossary

- Select bibliography

- Index