![]()

PART I

From Earliest Times to the Creation

of the Sultanate

![]()

1

The Earliest Kingdoms

THE origins of the present state of Brunei are lost in the mists of time and legend. It is not known when a kingdom which might be linked with present-day Brunei first appeared on the north-west coast of Borneo. Nor is it known when the ruler who founded the present dynasty emerged. History suggests tenuous links between kingdoms culminating in a state called P’o-ni by the Chinese, which emerged in the tenth century and from which a more reliable trace may be made. History also suggests a link between the ruling family of an early South-East Asian mainland kingdom known as Funan and the present ruler of Brunei. If the latter were substantiated, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah would belong to one of the oldest dynasties in the world. Brunei myth and legend also suggest a distant pre-Islamic past for the state, but these stories have been modified since the conversion to Islam so that the founder of the state and the dynasty is identified with the first Muslim ruler and centuries of pre-Islamic history are blotted out. Yet Brunei Malay culture, like Malay culture in Malaysia and Indonesia, has pre-Islamic elements deeply imbedded in it. One needs to consider how the earliest South-East Asian states emerged so that reasonable conjectures about how the Brunei state evolved may be made.

Our knowledge of early South-East Asia is fragmentary and subject to scholarly speculation and dispute. Not only are local sources sparse and of later date than the events they describe, but they either serve to glorify a dynasty or have acquired the texture of folk-myth and legend. Foreign sources are little better. Although the religions and culture of India profoundly influenced the emerging states of South-East Asia, Indian sources have remarkably little to say about the region. More revealing are the Chinese records, based upon the reports of Chinese envoys to South-East Asia and of South-East Asian embassies to the Chinese court as well as upon compilations prepared by scholars using information obtained by merchants and travellers. Here, however, as with the Indian and the later Arabic sources, one faces the problem of transliteration. A place-name may have been heard by a Chinese, transcribed into Chinese characters, and then transcribed again, centuries later, from the Chinese into English. One has only to consider the recent confusion over the transcribing of Chinese into English after the changes introduced during the 1970s, when Pinyin replaced the Wade–Giles system of transliteration and Peking became Beijing, Sian became Xian, and Canton, Guangzhou; or reflect that the names Ong, Wong, Wang, and Hwang, not to mention others, which grace the shop signs on a Malaysian street, may have the same Chinese ideogram. There is also the possibility that in making copies of documents over time, scribes have introduced minor transcription errors. No wonder scholars argue interminably over what places were meant. Confusion is only increased when sailing directions are taken into account, for not only do distances have to be converted from one form of measurement into another, but also measurements of time—all this assuming that the navigators were accurate. How far, exactly, was a day’s sailing? Therefore, in addition to place-names, scholars look for geographical details, items of trade, and references to gods, idols, forms of worship, types of dwelling, food, drink, and clothing—anything which might substantiate the choice of a particular location. As we try to locate the early Brunei kingdoms, examples of these problems will come to light.

Scholars have reached a consensus on the general outline of early South-East Asian history. There was a general long, slow migration of peoples south from mainland Asia, through the Malay Peninsula and the archipelago. Some branches came from the Indian subcontinent, others through China from central Asia. As people moved in, so others were pushed out or assimilated, while yet others remained in isolated pockets in more inaccessible regions; hence the confused ethnographic map of South-East Asia. By the beginning of the Christian era, a South-East Asian culture had evolved which, despite local variations and the continued existence of older tribal cultures, had common characteristics. One cannot do better here than quote the conclusions of the French scholar George Coedès (1968: 9), who said that these characteristics were

with regard to material culture, the cultivation of irrigated rice, domestication of cattle and buffalo, rudimentary use of metals, knowledge of navigation; with regard to the social system, the importance of the role conferred on women and of relations in the maternal line, and an organization resulting from the requirements of irrigated agriculture; with regard to religion, belief in animism, the worship of ancestors and of the god of the soil, the building of shrines in high places, burial of the dead in jars and dolmens …

He also mentioned similarities in mythology and linguistics.

This culture was influenced greatly by that of India. The coastal peoples of South-East Asia were capable seamen and established trade links with India across the Bay of Bengal. Indian merchants in their turn traded in South-East Asia. As trading links developed and merchant communities became established, influences spread. Hinduism and Buddhism were to exert great influence in the different states that adopted one or the other. Politically, the South-East Asian ruler, himself a merchant king, was attracted to the Indian ideal of the deva-raja, the god-king, which both Hinduism and Buddhism could accommodate and which bolstered the ruler’s prestige and authority and made possible the organization of a larger state. At South-East Asian courts, Indian Brahmans found positions as religious and political advisers, Indian merchants acquired positions of confidence, and ambitious Indian princelings could find wives and access to power. Thus began the ‘Indianization’ of South-East Asia. It was not brought about by a mass movement of peoples, but by the conversion of the ruling classes. At the local level, the old culture continued to survive with some modification, except that the great Hindu epics of the new High Culture percolated to the masses and became the basis for stories and shadow plays. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata continue to hold sway over the imaginations of many in South-East Asia to this day.

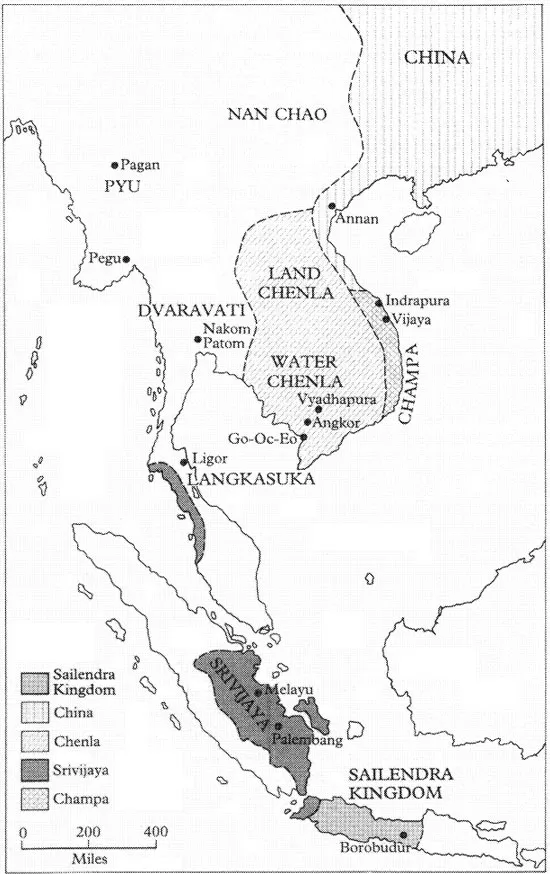

The first Indianized state of South-East Asia to impinge on history was Funan, centred on the lower Mekong Delta (see Map 1). Although it is called Funan, that name is really the modern Chinese pronunciation of two characters once pronounced ‘B’iu-nam’ which were attempts to transcribe the title of the ruler. As D. G. E. Hall points out, it is the modern Khmer word phnom, meaning ‘mountain’, in Old Khmer bnam. Thus the full title in the vernacular was kurung bnam or ‘King of the Mountain’, which was equivalent to the Sanskrit sailaraja (Hall, 1964: 24–5). The title has significance, for the mountain referred to was Mount Meru, the home of the gods in Hindu mythology. The Indianized South-East Asian state was based on a concept of Hindu cosmology in which the god-king was at the centre of his kingdom surrounded and served by levels of officials increasing in geometrical progression from four to eight to sixteen to thirty-two and beyond. The king was identified with a god, perhaps Siva or Vishnu. In Buddhist regions, he might be identified with a Bodhisattva, one who has achieved enlightenment. In both cases, the temporal authority of the king was buttressed by the belief that he was a god or was godlike. Loyalty, obedience, and service became acts of worship. The great temples at Angkor, at Pagan, and the Borobudur in central Java express this concept in architectural terms. The concept was expressed in spatial terms in the design of cities, with the king’s apartments lying at the centre of widening circles of palace, city, state, empire, and universe. The organizational structures of government reflected this concentration upon the centre and upon the person of the king. Of course, the hierarchical concept was not unknown to the West, and the European concept of the divine right of kings has parallels with the god-king. Nor was there uniformity throughout South-East Asia and over periods of time. However, the idea of a ruler’s sacredness if not divinity survived the coming of Islam to influence the Malay Sultanates of the Malay Peninsula and island South-East Asia, included among which was Brunei.

MAP 1

Early South-East Asian Kingdoms, AD 750

Funan was founded, so legend has it, by a prince named Kaun-dinya, who, following a dream, voyaged to Funan from either India or the Malay Peninsula. In a Chinese version, the queen of that country, ‘Willow Leaf, attempted to seize his vessel, was defeated, and married him. In another version, Kaundinya was a Brahman and married a daughter of the King of the Nagas. The Naga serpent was the traditional Hindu god of the soil. Whatever the true facts, Indian influence was introduced into the court of Funan and a line of kings descended from the union of the foreigner and the indigenous princess.

This was in about the first century AD. In the succeeding century, Funan extended its territories and in AD 243 sent its first embassy to China. At its greatest extent, Funan encompassed much of what is now Cambodia, southern Thailand and the northern part of the Malay Peninsula. Its capital, Vyadhapura (City of Hunters), was some 192 kilometres up the Mekong River and its port, Go-Oc-Eo, was a large metropolis on the Mekong Delta facing the Gulf of Thailand. The site has been excavated and shows trading contacts with China, Malaya, Indonesia, India, ancient Persia (now Iran), and even the Mediterranean. By the end of the second century AD, other Indianized states had emerged. Some, like those on the Malay Peninsula, had become vassals of Funan, but on the coast of central Vietnam, the kingdom of Champa maintained its independence. Like the Funanese, the Chams were a Malayo-Polynesian people. North of Funan was the Khmer kingdom of Chenla. All of these states made contact with China.

Funan reached a peak of power and influence under Kaundinya Jayavarman, who reigned from about AD 480 to AD 514. In AD 503, an imperial order of the Emperor of China highly praised Jayavar-man and bestowed upon him the title of ‘General of the Pacified South’ (Coedes, 1968: 59, quoting Pelliot). However, Jayavarman’s death ushered in a dynastic dispute which ended with the dismemberment of Funan and the emergence of Chenla as its successor. It is not necessary to go into details here. Briefly, one Bhavavarman, related to the Funanese royal family, had married a princess of Chenla and had become King of Chenla. Coedes believes that on the death of Rudravarman (the last King of Funan, who had been a usurper), Bhavavarman, a grandson of Rudravarman, intervened to prevent the legitimate line regaining the throne. Chenla conquered the northern part of Funan, which lingered on in the south until its final conquest by the Khmer king Isanavarman at the beginning of the seventh century AD.

Funan passed from history, but its influence did not. As the first powerful kingdom in the region, it had acquired an aura similar to that of ancient Greece or Rome in the West. Later rulers of kingdoms legitimized their power and burnished their prestige by proclaiming links with Funan. The Khmer kings of Angkor regarded themselves as successors to Funan and adopted the cults of the Naga princess and the sacred mountain. The Sailendra dynasty of Java in the eighth century consciously adopted the title ‘King of the Mountain’, and, as will be seen, there is a claim made for Brunei that its ruling dynasty is descended from the Funanese royal family.

Funan had been conquered by Chenla, which soon divided into a northern Land Chenla and a southern Water Chenla, a country of coastal plains and waterways, the old centre of Funan. Meanwhile, the Chams had extended their control further south in the eastern part of the Mekong Delta, and the territories on the Malay Peninsula, including the important trans-peninsular state of Langkasuka, had reasserted their independence. Water Chenla was further fragmented and at least part of it fell under the control of the Sailendra dynasty of Java. That this occurred supports the view that the Sailendras were descended from Funanese royalty who had escaped to Java. Their interest in Water Chenla might well have been an attempt to regain their inheritance. The connection did not last long, however, and in about AD 800 a united Khmer kingdom was created by Jayavarman II, who drove out the Sailendras and imposed Khmer control over the former Funanese states on the Gulf of Thailand and the Malay Peninsula. Jayavarman II then turned inland and extended his control as far as the great inland lake, the Tonle Sap, and the environs of Angkor. His successors continued his conquests and began building the cities and temples associated with their civilization. Indravarman I, who succeeded in AD 877, undertook the first irrigation works and built the Bakong, the first Khmer stone pyramid temple. Over the following centuries, a succession of kings—Hindu like Suryavarman II (1113–50), builder of Angkor Wat, and later Buddhist, like Jayavarman VII (1181-C.1215), builder of the city of Angkor Thorn and the Bayon temple— proclaimed their godhead in stone. They fought against the rival powers of the day, the Chams of Champa and the T’ai, advancing relentlessly from the north. At last, weakened by extravagant expenditure and continuous warfare, with the people turning to a new and gentler form of Buddhism which had no need for god-kings, Angkor succumbed to the T’ai in 1431. A new Khmer capital was eventually established at Phnom Penh in 1434.

The T’ai were a people who had migrated out of southern China and had established a series of states starting with Nan Chao in today’s Yunnan province of China in the seventh century AD. Nan Chao extended its influence into much of Burma and into northern Vietnam. In 1253, however, it was conquered by the Mongols. Smaller T’ai states had been established by this time in what is now northern Thailand. The most important of these were Sukhothai, which under King Rama Khamhaeng (C.1283-C.1317) extended power further to the south, as far as the Malay Peninsula, and Ayutthaya, which was founded by Rama Tibodi in the mid-fourteenth century and which eventually conquered Sukhothai and occupied Angkor in 1431. Under King Trailok (1448–88), Ayutthaya developed a centralized administration much more effective than that of its neighbours which survived until the nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, in the Malay Peninsula and the archipelago, kingdoms and empires also rose and fell. The mainland kingdoms had been largely interior states based on the irrigated cultivation of rice. There was trade with the outside world and states like Funan, Lang-kasuka, and Champa developed maritime trade, as did Ayutthaya, but the economic base of the mainland states was agriculture. On the Malay Peninsula and in the archipelago, agricultural economies like those on the mainland developed in central Java, but the majority of states elsewhere were coastal with their economies largely dependent on maritime trade. This survey will concentrate only on the largest and most influential, amongst them two powerful Javanese states which each developed from an agricultural economy to command maritime empires.

The essence of power in a maritime state is control of the sea and of the trade which plies upon it. A glance at a map of South-East Asia (see the back endpaper map) shows clearly that the Malay Peninsula and the islands of Indonesia divide the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean on the west from the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea on the east. By the beginning of the Christian era, maritime trade had developed between India and South-East Asia and China and South-East Asia, as well as within the island world of the archipelago itself. Trade was carried in Indian, Chinese, and Indonesian shipping, the last bringing goods to favoured ports from the extremities of the archipelago as well as participating with Indian and Chinese traders in the trade with their home ports.

Another feature of the trade was dictated by the prevailing winds, the monsoons. The North-east Monsoon, blowing from November to April, favoured ships sailing from China to the archipelago and from the archipelago to India. The South-west Monsoon, from May to October, favoured shipping sailing from India to the archipelago and from the archipelago to China. Two consequences emerged. The first was that it was possible to make a return journey within the year from China and India to the archipelago if one exchanged cargoes at a port in the archipelago. Similarly, archipelago shipping could travel to and from such a port to either India or China by using one monsoon on the outward voyage and returning on the other. There was no incentive to travel the distance between India and China in the one ship for that meant waiting in the archipelago for the monsoon to change anyway. The second consequence was that certain shores were more protected than others from the prevailing monsoon. In particular, the east coast of the Malay Peninsula received the full force of the North-east Monsoon and the southern coast of Java and the west coast of Sumatra that of the South-west Monsoon. The most protected ports were to be found on the north coast of Java, the east coast of Sumatra, the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, and the south and east coasts of Borneo. The Java Sea was protected from the main force of the monsoons, as was the western side of the Philippines. The north-west coast of Borneo was exposed, but particular sites on it were protected, as will be shown below.

It is also clear from the map that ships travelling from east to west and vice versa, or desiring to reach ports on the coasts most protected from the monsoons, had restricted passage. On the east was the relatively broad approach between Vietnam and Borneo, but on the west there were the narrow Strait of Malacca and the narrower Sunda Strait. A power which controlled either or both of these was in a position to control the maritime trade of the region. This fact was soon understood by the rulers of states on Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula. Indeed, Funan had shown the way here as in other things, for at its height it had controlled the eastern approaches by its command of the Gulf of Thailand from its port at Go-Oc-Eo and the approaches to the Strait of Malacca by its control of Langkasuka and the northern Malay Peninsula. In Funan’s case, this resulted in the transhipment of goods over the narrow part of the peninsula using the river system and porterage.

The first great maritime empire to arise in the archipelago was that of Srivijaya in the sixth century AD. Its capital was near present-day Palembang on the east coast of Sumatra. It was a Buddhist kingdom. In AD 671, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim I-tsing said that there were 1,000 Buddhist monks there and on his return from India in AD 675, he stayed for ten years at Srivijaya studying and translating Buddhist scriptures. By the eighth century AD, Srivijaya had conquered the coastal states of east Sumatra and the states of the Malay Peninsula, thus giving it firm control of the Malacca Strait. It also controlled both sides of the Sunda Strait. All shipping was compelled to call at Srivijaya, which thrived on the trade and the charges and levies it could impose.

Unlike the mainland states, Srivijaya left no magnificent remains. This was partly because of the lack of readily accessible building stone in the marshy coastal flats and the consequent reliance on wood as a structural material. It may also point to the lack of a large peasant population which could be recruited for forced labour on a seasonal basis. Palembang’s wealth was based on trade and its empire was far-flung, consisting of the command of ports and coastal city-states either coerced or persuaded into allegiance. In between the coastal cities and their immediate hinterland would be long stretches of coast fringed with mangrove and nipa swamps. Only where rivers penetrated the interior was it possible for internal trade to develop and a riverine port to arise. In many respects, Srivijaya was not well placed, being some 120 kilometres up the winding Palembang River beyond the swampy coastal fringe (Wheatley, 1966: 293). But at some point its rulers gained the allegiance of the orang laut or men of the sea, skilful seafarers of the islands south of the Malay Peninsula and off Sumatra’s east coast, nomadic and semi-nom...