![]()

1

PROFESSOR MARTIN BANHAM: A PERSONAL TRIBUTE

Dapo Adelugba

Although Martin Banham is now sixty, it is the image of ‘young Martin’ that remains indelible. Born in December 1932, he came to Nigeria in September 1956 at the age of twenty-three to teach literature at the invitation of Molly Mahood. I was to come under his influence two years later when I was admitted to the University College, Ibadan, U.C.I., then a college of the University of London, in September 1958.

Martin Banham was at Ibadan during the “fences” disturbances of the 1956/57 academic session. He was said to have put up on the Notice Board in the Department of English, in the spirit of camaraderie, two significant lines from a metaphysical poem,

“Stone walls do not a prison make

Nor iron bars a cage.”

This piece of witticism was dearly paid for by the young enthusiast, as gossip had it at that time.

Be that as it may, the image of a handsome, young intellectual with flowing, auburn hair, in white shirt and white shorts, smiling urbanely as he walks past colleagues and students on the Faculty of Arts corridors, remains vivid in my memory and I daresay also in the memories of most students of English at Ibadan in the middle to late 1950s.

I was Martin Banham’s student in my “suspense year,” the 1958/59 academic session. His fluency of speech and felicity in phrasing, his wit and humour, his originality in literary appreciation, his warm humanity and his love of the theatre became evident within the first few months of my association with him. In the three years of the English Honours programme I pursued from 1959 to 1962, I came to know Martin Banham and my other lecturers and our Professor, Molly Mahood, quite well. The Ibadan programme had a strong Oxbridge flavour and the tutorial system was very effective. Molly herself is an Oxonian and was already a well published scholar during my years as an undergraduate. She was very close to her students and colleagues and she invited each set of English Honours students to dinner in her house once a term. We were indeed very proud to be ‘Mahoodians’.

Since a bit of university gossip, especially with the present benefit of distance in time, is unlikely to hurt anyone, it may not be out of place to reveal here that, as students, we were aware at that time of the constant by-play between Professor Molly Mahood and her two lecturers who were, in her view, perhaps a little too devoted to the theatre. Professor Mahood, a scholar of Shakespearean drama and poetry, was not against the love Geoffrey Axworthy and Martin Banham showed for the theatre but she probably felt that they spent too much time at the Arts Theatre.

Nonetheless, the turn of events was to favour the theatre buffs. When the university started a School of Drama in 1962/63 with the assistance of a Rockefeller Foundation grant, Geoffrey J. Axworthy was on the spot to head it as Director and Martin Banham to assist him as Deputy Director. Correspondence in the files reveals that Professor Molly Mahood supported the candidacy of both Geoffrey Axworthy and Martin Banham for the new positions for which their work at the Arts Theatre, ironically, seemed to have prepared them. Molly Mahood eagerly looked forward to the growth, in subsequent decades, of drama and theatre in Nigeria which she believed the School of Drama would help to promote. Time has proved her right.

If Martin Banham’s contribution to the work of the Department of English at U.C.I. was commendable, his input in the years he spent at the School of Drama – 1962 to 1966 – was even more significant. He proved an effective lecturer in dramatic literature, dramatic criticism and theatre history as well as a good actor / actor-trainer, a good director and all-round man of the theatre. He also proved his mettle as an administrator. A good and prompt correspondent, Martin Banham was relied upon by Geoffrey Axworthy to do most of the official correspondence for the School of Drama during their years of collaboration.

In his ten years at Ibadan (1956–1966) Martin Banham contributed effectively to the growth of literature, drama and theatre arts as a lecturer, a trainer of actors, of directors and of theatre personnel in general, an arts connoisseur and critic, an arts administrator, an actor, a director, a promoter of student creative writing and productions, a broad-minded, intelligent and forward-looking pioneer and leader.

I had a direct exposure to his meticulousness as a theatre director in 1965 when I was invited from my teaching base at the Ibadan Grammar School to play the Tramp in Martin Banham’s production, for the University of Ibadan Yeats Centenary celebrations, of The Pot of Broth. Ebun Clark, one of the lecturers at the Ibadan School of Drama who was later to do an M.Phil. at Leeds under Martin’s supervision, played the role of the lady of the house in the same production. Ebun and her husband, J.P. Clark, were and have remained good friends to Martin.

Both in the Arts Theatre Production Group (ATPG), which he pioneered along with others like Geoffrey Axworthy and Harold Preston, and in other drama and music groups of Ibadan, Martin Banham acted in a wide variety of plays, musicals and operas and directed a good range of plays in the Euro-American world repertory from the classical to the modern period.

The most remarkable aspect of Martin’s decade at Ibadan was the constancy of his warm encouragement of and participation in staff and student initiatives. He published in 1960 an anthology entitled Nigerian Student Verse, choosing the most qualitative poems from the student-edited poetry / criticism magazine, The Horn (of which John Pepper Clark was pioneer editor), and from a few other student magazines. With Geoffrey Axworthy and George Jackson, he was supportive of the initiatives of the University College Ibadan Dramatic Society (UCIDS), a student group which took plays round the dining halls of the Halls of Residence, when the Arts Theatre was closed for repairs in 1960, and which embarked on country-wide tours during Easter vacations in the early 1960s along the lines of a national student policy to interact with the nation outside the ivory towers. The Theatre-on-Wheels in 1964 was a further development by Geoffrey Axworthy and his technical director, William Brown, of this initiative when the School of Drama celebrated the quatrecentenary of William Shakespeare’s birth with a country-wide tour of excerpts from selected plays by the bard.

Martin Banham’s literary and dramatic criticism has always shown his concern for high standards and an appreciation, even when it is severe, of honest effort. His reviews in Ibadan (edited by Molly Mahood), The Horn and in other academic and student journals and magazines show his perspicaciousness, his cosmopolitanism, his wit and humour, and would make excellent reading even today.

Professor Martin Banham has, in the twenty-six years since his return to Great Britain, become a central figure in African drama and theatre studies. He is one of the few academics occupying Drama and Theatre chairs in the United Kingdom today, and that is no mean achievement. But the work Martin did in the 1956–1966 period at Ibadan and in Nigeria stands out in its own right and looks, in retrospect, like his rehearsal for the Leeds revolution. It prepared him for his return to his alma mater, the University of Leeds School of English, which his Workshop Theatre has put in a key position in the drama and theatre studies map of the world on account of his firm commitment to the duality and complementarity of theory and practice.

“A merry heart goes all the way”. Martin Banham’s constant smile is a source of encouragement to his colleagues and students even in the most difficult and trying moments. Martin is a marvellously amiable and extremely helpful person who takes joy in the progress and success of other people. He has no room for pettiness in his heart. For example, he played a very active role in the award ceremonies of the

honorary D.Litt. of Leeds in 1973 for W

ple Soyinka (who was his junior in the Leeds English Honours programme in the 1950s) and he reportedly drove Soyinka around Leeds to find an appropriate suit to hire for the occasion. They both enjoyed that very much.

As External Examiner from 1969 to 1972, Martin Banham helped once again in the development of the University of Ibadan School of Drama during the period of W

ple Soyinka’s leadership. Martin was also a constant visitor to other African countries, such as Ghana and Sierra Leone, as resource person for workshop, seminars and conferences in drama/theatre arts in the late 1960s and in the 1970s.

Martin Banham’s books and articles constitute a remarkable output. His African Theatre Today, co-authored with Clive Wake, his Drama in Education co-edited with John Hodgson, and his edited magnum opus, Cambridge Guide to World Theatre, compiled with the collaboration of a small team of top-flight scholars in various continents as Editorial consultants, are significant landmarks. But his practical work in the theatre must always be taken into consideration in an assessment of his contribution to knowledge, ideas and skills. The Leeds Workshop Theatre has deservedly earned a high reputation in the two and a half decades of Martin’s directorship of it.

Professor Martin Banham is today a central figure in Drama and theatre studies on a global level. We at Ibadan in particular and in Nigeria in general take great pride in his achievements and, in warmly wishing him more successes in the years ahead, we implore him to keep up all his good qualities and to keep the flag of excellence flying. We believe that there is a lot more yet to be accomplished. For, after all, life begins at sixty.

![]()

2

BROKEN MIRRORS: ART AND ACTUALITY IN ZIMBABWEAN THEATRE

Robert McLaren

Theatre in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe shares with other nations colonized by the British a theatre history characterized by indigenous dramatic forms suppressed in favour of white minority colonial theatre. The armed struggle for independence was also a struggle for cultural renewal and the revival of traditional performance in the service of the liberation struggle. At independence the revolutionary thrust encountered established colonial cultural institutions and practices. While the latter dominate at the public and media level, a new flourishing of democratic theatre at grassroots level has swept the country in recent years, producing numerous fulltime theatre groups which carry theatre to every province.1

In the early years the theatre of these groups was politically engaged, often socialist or anti-apartheid in content. Since then the world has seen the collapse of the socialist countries of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union itself. Apartheid in South Africa has collapsed with the birth of majority rule. In Zimbabwe an IMF Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) has been imposed, hurling the population, including the artist, into the jungle of so-called Free Market Forces. All these momentous changes have transformed the activity of the community-based theatre groups. Either to survive or simply in order to swim with the tide, most have abandoned the earlier political and socialist thrust for anything that will secure them financial assistance from donor agencies or big business or yield commercial profit.

The University of Zimbabwe began practical drama courses in 1985. In addition to productions and projects resulting from course work, the University organized extra-curricular productions and established a political theatre group, Zambuko / Izibuko (‘river-crossing’ in Shona and Ndebele).2 Such activities have been open for all Zimbabweans to participate in. The aims and objectives of drama at the University of Zimbabwe were stated to be the following:

1. The determination to base our work in the lives, experiences, thoughts and culture of the Zimbabwean people and their brothers and sisters in others parts of Africa and the progressive world.

2. The effort to develop an ideological direction in key with the most progressive elements in Zimbabwean society as represented by the liberation struggle, the struggle for majority rule, the struggle against racism, colonialism and imperialism, and the struggle for a socialist Zimbabwe.

(Drama, Faculty of Arts, University of Zimbabwe)

“Disrupting the Spectacle”

In Gunter Grass’s play, The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising, the playwright has Bertolt Brecht rehearsing his version of Coriolanus when the Berlin Uprising of 1953 breaks out. Coriolanus, as you will recall, begins with a plebeians’ uprising against the dearth of corn. Grass’s play thus explores a moment when a revolutionary playwright, rehearsing an uprising in art, is overtaken by an uprising in actuality.

In South Africa a Soweto group performs in the street. In the play they perform, political prisoners are ceremoniously called out of jail. The police arrive and put an end to the ceremony. At that precise moment the police do arrive and “disrupt the spectacle” – not with dramatic impersonations but the Casspirs, guns and teargas of actual South African police. The actors jump fences and disappear behind the houses to re-group and perform again elsewhere. Again actuality has invaded art – with the important difference that in the Soweto example it is not the artifice of a playwright but a scene from life and death reality.3

In Africa art and actuality constantly overlay and part. Where modern drama is known and performed, art articulates itself as something distinct from actuality but only temporarily and with fragility. The performance and spectator/participant norms of many modern African plays take this for granted. This is especially so in the case of ritual where the performed act and the real thing are difficult to distance from each other.4

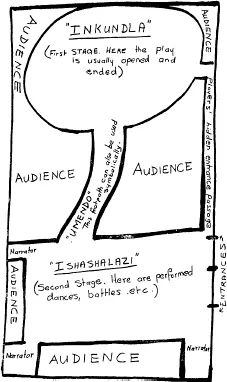

1. Stage plan by Mutova for the original production of uNosilimela

Staging and blocking in Africa, too, tend to facilitate this. Semiarena, in-the-round and multiple staging are common forms. If actors play to each other by facing those they are talking or relating to in the play, the audience feels excluded and can soon become restive. Thus opening out the action and the dialogue to include the audience is a common element of blocking in African theatre.

The work of Credo Mutwa, whose uNosilimela5 is an attempt to recreate the original staging of traditional Zulu performance and adapt it to modern theatre, is full of scenes in which there is nothing to separate the spectator and the action except the tenuous and repeatedly ruptured veil of art. The wedding scene in uNosilimela is an example of a ceremony which, in real life, it is not normal to sit or stand and watch without joining in. In the theatre, especially wher...