![]()

PART ONE

The inter-war years

![]()

1 Some aspects of the demand for funds

The study of the finance of British industry involves an examination of part of the mechanism whereby additions to and replacement of the stock of capital are brought about. Frequently belittled, and often ignored, the question of finance raises some interesting and for the early part of this century largely unanswered questions; regrettably, due to the absence of adequate information, only tentative answers can be put forward. Among such questions are those relating to the determinants for long-term funds, changes in the demand for external funds, the division between short- and long-term borrowing, and between debt and equity borrowing, and how effectively industry used the financial resources put at its disposal.1 Further, the assumption is usually made, on the capital using side, that the only changes that occur, or are important, are those involving the acquisition of real assets. But in the case of business firms, changes in capital formation are almost invariably accompanied by changes in holdings of financial assets. Thus, ideally, the supply of funds (the sources of funds), should be related not only to the level of investment in plant and equipment and stocks, but also to the acquisition of all assets, including financial ones. More often than not it is assumed that additional funds are used solely for the purposes of capital formation and that no part finds its way into financial transactions. It would be desirable to be able to separate the two streams of expenditures, but in practice it is not possible even to identify a rough order of magnitude for the latter for any length of time (see Chapter 4).

In looking at the finance of industry the main distinction made is between internal financing, the user drawing upon his own level of savings, and external, where a claim is made for someone else’s savings. In so far as internal funds are concerned the only decision that matters is that of the firm; no external party is involved. But in an indirect way even internal sources are subject to some degree of testing by the market. Buyers must be prepared to pay a price for the firm’s product which covers depreciation and yields a net profit, so enabling the firm to finance replacement or expansion from within. External financing, since it draws on the financial resources of other sectors, must pass more stringent tests but one’s which are not consistent over time, or common to all borrowers. Also involved in the case of external borrowing is the important distinction between fixed interest (loans of different durations and conditions as to security) and equity capital where there is no fixed date of repayment or rate of return.

The aggregate picture of capital funds brings with it several problems and the need for a great deal of caution in interpreting trends. In such a presentation opposite movements among individual units cancel each other out. The larger the number of units included within the total the greater the likelihood of cancellation. For example, if all companies combined show a negligible net balance for security financing in a given year it does not mean that borrowing was unimportant for every firm; some may borrow heavily from the market while other firms may be redeeming debt. In practice the derivation of net totals tends to understate the share of external borrowing and to exaggerate that of internal funds. Ideally it would be desirable to have available figures of inter-company flows but these do not exist even for more recent periods. The other temptation is to adopt too great a degree of association between sources and uses of funds, and between maturity periods on both sides of the balance sheet. It is all too easy to link depreciation provisions to the financing of gross fixed capital formation alone, but as emphasized below the practice is often different. Industries displaying slow growth use such funds in other ways and this may well be true of all industries in times of depression. In the matter of maturities long-term funds would normally be associated with the financing of long-term investments such as plant and equipment, and buildings, while short-term funds such as bank loans would be used to carry stocks of materials and finished goods, or to acquire financial assets. In practice long-term funds are used for the continuous circulation of short-term assets, while firms with very fast rates of growth may use short-term funds in part to finance long-term assets, and the substitution between maturities is probably greatest in the case of such firms. Normally their long-term liabilities would be given priority in financing long-term assets, and short-term liabilities preference in financing quick assets, but it is essential to be aware that there may well be important exceptions to this general assumption. As a rule, of course, company statements do not show the exact items on which funds obtained from a given source were spent.

Such qualifications and cautionary warnings apply to comparatively recent series on the financing of company activity, such as those for the post-1945 years. Since there are no comparable figures for the inter-war years even greater care and awareness of the problems involved are essential. It was not until the 1948 Companies Act that some long due degree of uniformity was imposed on company reporting; before that it was extremely varied and very haphazard. For the inter-war years there is no composite series on the uses and sources of funds: the information with which to make some inferences regarding the general picture of the demand and supply of funds consists of a series of quite separately derived estimates. The best that can be done, therefore, given the independent nature of the compilation of such items as investment, internal funds, and long-term external borrowing, is to note the extent to which changes in one series coincide roughly with those in another. They can in no way be added together to produce illuminating ratios, that is, one cannot add internal funds to external borrowing to give total sources of funds. While it is possible to make a loose association between uses, corresponding to net changes in assets, and sources, changes in liabilities, it is not possible to compile a table of the sources and uses of funds which come to an identical total.2 What follows, therefore, is an attempt at some generalizations as to the demand for funds with such severe shortcomings in the material very much in mind.

The pre-1914 financial background

In attempting to provide a general indication of the nature of the financing of industry immediately prior to the First World War, as a background to the more detailed study of inter-war practices, ‘we are at once’, in Lavington’s words, ‘met by the great difficulty that the available statistical information is exceedingly meagre.’3 Such conjectural estimates as are available suggest that the demand for external funds in this period was small, and that even in times of boom when the ratio of external to total financing would be expected to rise, that not more than 10% of real home investment was financed by market borrowing and of this only about a third was raised by new companies.4 For the period 1911–13 A. K. Cairncross estimated that the value of security issues made by new companies averaged some £8m., but this sum included issues by railways, investment trusts, etc. Earlier, in 1907, the total value of issues for domestic investment purposes, excluding financial and public utility issues and correcting for cash payments to vendors, was no more than £13. 8m. It would seem reasonable to conclude that the volume of new issues by new companies was therefore modest. Such stock market borrowing as was done by such companies appears to have been largely in the provinces with the amount involved being at the most £2m. to £3m. The rest was obtained by private negotiation between business partners or with well-connected wealthy families and ‘generally by the investment of their own capital by the directors or owners and their friends’. Extra funds also came from shares privately placed by public companies formed without a prospectus, the shares later being unloaded on the market, and a rough estimate was that such channels produced ‘about £12m. in the provinces for the purpose of home investment’.5

Companies already in possession of their capital seemed to have raised rather more of their needs from the market. They were responsible, by number, for about half the issues of home industrials on the London market prior to 1914. In the years 1911–13, by value, such issues averaged £22.5m., but this figure includes utilities and financial issues. Making an allowance of some £9m. for the placing of unsold shares and sales in the provinces of the stock of companies not formed under the Companies Acts, a rough estimate of £54m. is obtained which represents the sum subscribed to home industry in 1911–13. Deducting an estimated one-sixth for cash payments to vendors and for purchases of land and existing assets the figure emerges at £45m., which is probably the maximum of the average amount of capital supplied by the stock market for real home investment prior to the war.

It is probable that at least half the additions to the capital of industrial concerns came from undistributed profits. The Colwyn Committee of 1927 (Committee on National Debt and Taxation) in a sample enquiry for 1912 found that out of trading profits amounting to £312m., companies put to reserve £102m., which after tax was £96m., and of this sum £48.4m. was for the manufacturing sector. What was true then of this immediate pre-war period was probably more so of earlier years since a large part of the manufacturing industry was in private hands, the main market borrowers being public utilities and the distributive trades.6 The general position would appear to have been that ‘the vast majority of joint stock companies coming into being each year were either already in possession of their capital or obtained it by way of private negotiation’.7 Further, that market borrowing by old companies greatly exceeded that by new ones, and that retained profits were a more important source of finance than outside funds. Thus, the amount of external finance going into manufacture as such was not very large and of that amount only a comparatively small proportion was raised by public issue on the market.

The availability of internal finance

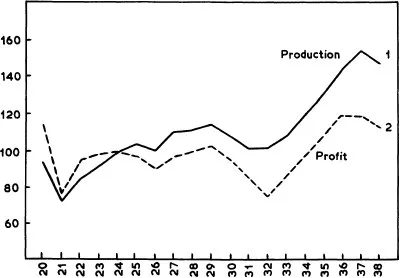

From a general standpoint the demand for long-term funds by industry may be taken as dependent on the level of retained income in relation to investment. Savings depend on gross profits less various deductions, while the level of gross profits is mainly dependent on the level of output, the latter also being one of the most important influences on investment activity. As can be seen from figure 1.1 profit behaviour in the inter-war years was closely related to output variations (the correlation coefficient between the two series being 0.71).

After the immediate post-war slump of 1921 the growth of output was quite steady, apart from the 1926 setback and the depression of 1929–32. Profits followed the same general path, tending to fall more abruptly in periods of reduced activity and rising more rapidly than output in periods of recovery; this pattern is consistent with the interpretation that in periods of expansion costs do not rise at the same rate as output and selling prices, while in the recession falling output leads to rising unit costs and reduced profit margins. The overall impression from the index of industrial production given in figure 1.1 is that the periodic setbacks in output after 1922 were not as sharp as the changes which occurred in other leading economic indicators, particularly unemployment which rose from 10% in 1929 to 22% in 1932. Taking the period 1920–6 the cumulative rate of growth of output was 2.8% per annum, and from 1929–37 it was 3.3% per annum. Among the reasons suggested for this rise was the improvement in the terms of trade, a considerable amount of innovation in the newer industries, cheap money, while rising real incomes sustained consumer demand in the recovery of the 1930s. It had also become less attractive to lend abroad so diverting capital to the home market. Although home investment in money terms in the inter-war period seems rather low (see figure 1.3, p. 11) it should be noted that capital goods were relatively cheap so that domestic investment was in consistent relationship to growth.8

Figure 1.1 Manufacturing production and gross profit, 1920–38 (1924 = 100)

Sources: 1 K. S. Lomax, ‘Growth and Productivity in the United Kingdom’, in D. H. Aldcroft and P. Fearon, Economic Growth in 20th-century Britain, 1969.

2 P. E. Hart, Studies in Profit, Business Saving and Investment in the United Kingdom 1920–62, vol. 1, 1965.

While the overall picture of manufacturing output displayed reasonably stable growth, very different performances were recorded by individual industries as measured by comparing the average for 1936–8 with the base year of 1924 = 100. Among those which might be classified as fast growers, whose output rose by more than 75% over the period, were vehicles (215), electrical engineering (213), metal goods (177) and non-ferrous metals (175).9 This growth in output was associated with increased labour productivity, there being increases in the range of 0.5% to 2.0% per annum in the case of the above industries.10 Industries which displayed moderate levels of output growth for the period, output increasing by between one-quarter and three-quarters, were food (163), tobacco (153), precision instruments (152), chemicals (143), ferrous metals (132), clothing (130) and mechanical engineering (126). Relative stagnation, however, hit several industrial sectors and they failed to display any significant improvement in output over the period. Among these were textiles (118 – separate figures are not available for cotton which would probably be lower), leather (102), shipbuilding (102 – in 1932 the index fell to 11.3), and mining and quarrying (92). Expansion thus centred on the newer industries and owed its impetus to the fruits of technical change, lower unit costs with economies of scale, and a changing consumption pattern sustained by rising real incomes.

With few exceptions (leather, woollens and paper had little or no trend, and cotton had a clear downward trend) industries in the manufacturing sector experienced a general upward trend in profits in the inter-war years. Fluctuations in the profits of individual industries mirrored in varying degrees the general movements displayed by the index of gross profits for all manufacturing given in figure 1.1. In relation to output changes in individual industries, fluctuations in gross profits moved in sympathy, the latter frequently being greater than the former. For example, in the case of an industry with a record of considerable expansion (vehicles) output increased by 133% between 1924 and 1929, while profits rose by 229%; in the depression output fell by some 20%, profits by 51%, and in the ensuing recovery output rose by 108% causing profits to jump by 234%. In the case of a leading example of a declining industry, cotton, the response of profits to output changes is even more pronounced. Taking the output figures for textiles as an indicator for cotton, output fell continuously from 1924, apart from a brief and minor revival in 1927, being 16% lower i...