This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Growth and Role of UK Financial Institutions, 1880-1966

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1971, this monetary theory text looks at the United Kingdom's financial institutions and financial statistics as published by the Bank of England or by Government agencies from 1880-1962.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Growth and Role of UK Financial Institutions, 1880-1966 by D.K. Sheppard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 The Growth of UK Financial Institutions and Changes in the Financial Environment 1880–1962

Introduction

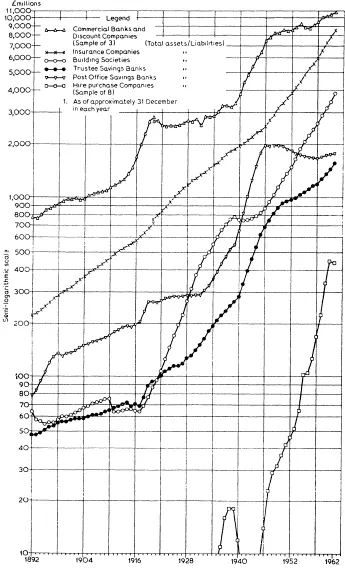

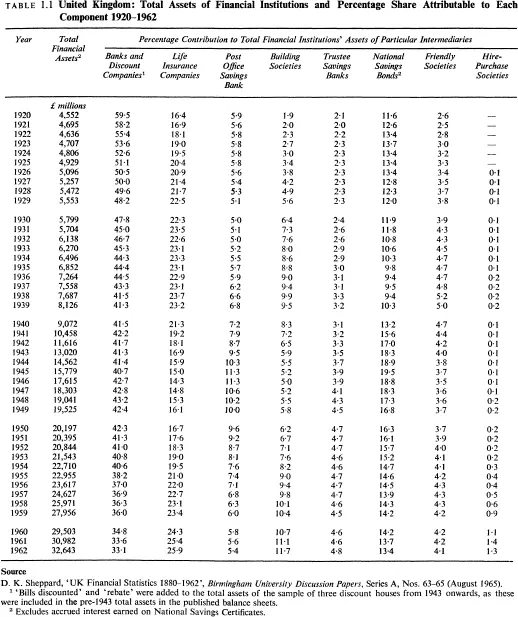

Graph (1)A and Table 1.1 introduce an empirical account of the development of the UK financial structure since 1880. Together, they trace out the growth paths of the assets of many leading groups of financial institutions; and they show both the absolute share and the relative proportion of all of these assets that each of the selected groups had on an end-of-year basis from 1920 to 1962.

The record is not complete. Deficiencies in the published statistics made it impractical to incorporate the UK business of the overseas banks, the assets of the investment trusts, unit trusts, private trust and superannuation funds, and of the accepting houses and most of the merchant banks. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that the UK business of the omitted institutions would exceed, say, £16,000 million – e.g. 50 per cent of the recorded evaluation of the included institutions’ assets.1 Moreover, in some respects, the omissions are salutary inasmuch as their inclusion would accentuate the tendency to incorporate inter-institutional claims and make it more difficult to standardize the method of asset evaluation.2 As a consequence, the recorded data seem to be comprehensive enough to provide an indicative account of the main trends in the growth and the distribution of UK financial savings as well as outlining the development of the main UK-based financial institutions.

Graph (1)A and Table 1.1 indicate that there was a marked change in the consolidated total and in the assets of each of the selected groups of financial institutions over the period.

Between 1920 and 1962, for example, the table shows that the total financial assets of these institutions rose from £4·6 milliard to £32·6 milliard. Over the same period, the graph depicts that by group institutional assets rose as follows: the bank and discount companies’ assets increased from £2·7 milliard to £10·8 milliard. Those of the insurance companies rose even more rapidly from £0·7 milliard to £8·5 milliard, and so did the assets of the building societies and the consolidated assets of the sample of eight leading hire-purchase companies. The building society assets increased from £90 million to £3,800 million, while those of the hire-purchase companies rose from £1 million to £440 million. Though their growth was less spectacular, the assets of both the Post Office Savings Bank and the trustee savings banks burgeoned over the years. The former’s assets increased from £267 million to £1,760 million and the latter’s rose from £94 million to £1,555 million. The overall increase in the consolidated assets of these institutions reflects a sizeable rise in the pace of financial activity; particularly when this increase is compared with the growth of GNP over the same period – £6 milliard to £25 milliard.

The graph illustrates that relative to each other the growth rates of the constituent groups of institutions changed considerably, and that there was also considerable variability in the growth rates of each group of institutions – except for the insurance companies, whose rate of asset accumulation barely deviated between 1892 and 1962.

For instance, while the graph shows that there were certain similarities between the rates of growth enjoyed by the trustee savings banks and the building societies throughout most of the period, it illustrates that the movements of both the commercial banks’ and the Post Office Savings Bank’s assets were quite dissimilar. In 1916, 1921–4 and 1954–6 the two sets of rates were negatively related. Moreover, the graph shows that in the post-1920 peacetime periods the building societies and the trustee savings banks did well; while the assets of the banks and of the Post Office Savings Bank either expanded slowly or declined. In contrast, from 1892 to 1914, from 1914 to 1920, and from 1939 to 1946 both the banks and the Post Office Savings Bank enjoyed periods of relatively high rates of growth, particularly during the periods of national emergency; whereas the assets of the building societies and to a lesser extent the trustee savings banks either declined or grew much more slowly. Finally, the graph highlights the extraordinarily rapid expansion of the sample of hire-purchase companies in the post-1919 period. From 1920 to 1939 their assets grew at a compound annual rate of 16 per cent and from 1946 to 1962 the rate was 24 per cent; it was 27 per cent from 1954 on to 1962.

(1)A UK Financial Institutions: Credit Series 1892–1962

Source: See Appendix, Table (A)3.4

Naturally, the sustained discrepancies between the growth rates of groups of institutions meant that over time each group’s share of the market for loans and institutional claims changed significantly. Table 1.1 shows that in 1920 the banks accounted for 60 per cent of all institutional assets; by 1962, their share had fallen to 33 per cent; whereas the shares of the insurance companies and the building societies had risen from 17 per cent to 26 per cent and from 2 per cent to 12 per cent respectively. Moreover, it shows marked oscillations in the shares of these and the other groups. In effect, the graph and the table indicate that the UK financial structure changed considerably over the period, and that much of this change must be explained by sudden as well as slow changes in the financial environment. This is to say that qualitative factors, often exogenously determined, played an important role in the development of the financial sector.

The wars and the subsequent pressures which were exerted in the post-war reconstruction had a pronounced impact; so much so that in much of the post-1914 period the financial sector perhaps evolved as it did in response to particular needs: the needs of the Government to harness savings to finance the war effort; the needs of the household sector to satisfy its wartime deferred demand for houses and consumer durables. The radical changes in the sources of exercisable demand pressures for institutional loan accommodation were such that for purposes of analysis it seems that the statistical record should be examined in five sub-periods rather than in one.

While the wartime emergencies and the adjustments which followed them account for the major discontinuities in the series, shares and growth rates, other developments of a qualitative nature played a role in the evolution of the financial sector.

The pre-1880 changes in the institutional environment had a considerable influence at least up to 1914, in the sense that by 1880 nearly all the recorded institutions were operating financial intermediaries within a chosen or legislated area of specialization in the financial market.

From 1880 onwards, the Government became increasingly important as a decision-maker. It adjusted the established regulating legislative framework with greater ease to meet its needs; it stepped up the development of its own schemes for attracting savings, and by incentives and eventually directives it exerted increasing pressure on the portfolio choices of the privately controlled institutions to finance its needs or other desired social objectives, e.g. housing. As a side effect, its actions had considerable influence on the growth or retardation of the banks, the trustee savings banks, the Post Office Savings Bank and the building societies by altering the relative attractiveness of their obligations.

Less dramatically but significantly inasmuch as it affected the nature of the Government’s directives and intervention, the long-run change in the UK’s international economic position was influential. The decline in the British Empire and the accompanying erosion of sterling’s role as an international currency affected the sources and placements of savings received and made by the institutions. The UK financial system slowly switched from being a net supplier to a net absorber of external short-term funds. The switch resulted in considerable changes in the operating practices of the established institutions, and it created opportunities for expansion which were readily seized by some of the more independently operated intermediaries – the merchant banks.

After 1880 the financial institutions also took steps which influenced the environment and therefore played a part in shaping the development of the financial sector. Each group established trade associations which it then proceeded to strengthen in order to regulate within-group competitive behaviour as well as to represent the group’s interests to the Government. Through the expansion of the inter-group loan accommodation and/or equity ownership, the liaison between the separate groups improved. Within- and between-group conjectural variation became well recognized. Within-group borrowing and lending rates became standardized and knowingly geared to the rates of other groups to avoid undue competition. Equally important was the tendency, which often resulted from Government legislation, for each group to select a particular type of financial savings as well as a particular range of outlets in which to place its funds. The institutional lending and borrowing practices became segmented. The emerging gaps in the intermediating process, such as the excess demands for export finance, for consumer finance, for medium-term industrial loans, for loans to local authorities, only tended to be filled on Government sponsorship or, rather later, through the activities of intermediaries which were not absorbed by the close-knit institutional arrangements.

Naturally the external shocks, long-run influences and institutional generated market imperfections noted above were not the only factors which influenced the overall pattern of financial activity. The growth in tangible wealth, the growth and change in composition of expenditure, the growth and more equitable distribution of disposable income, the degree of unemployment, the level of prices, of interest rates, of tax rates, and expectations about these undoubtedly played a part in dictating the nature and composition of period changes in assets and liabilities of the institutions. After all, these institutions’ liabilities and therefore assets would not have grown at all if the non-financial private sector had been unwilling to take up the readily realizable secure wealth claims they issued in exchange for this sector’s savings. Nevertheless, I consider that the non-quantifiable factors were important too, and would urge that their influence should be borne in mind in designing and interpreting econometric relationships which are structured to explain the growth or the role of the financial sector.

The most important of these qualitative factors are set out below with an assessment of what seems to have been their likely effect in terms of their particular influence on the financial sector. The broad environmental background is outlined, and then the effects of the Government’s intervention, of the institutions’ own activities, and of the change in the international environment are traced and examined successively in the post-1880 period. Naturally this record is not complete and the interpretations of the intent as well as the effects of some of these developments are certainly contentious. Neither the authorities nor the institutional trade associations have been particularly eager to argue that they intended to channel the flow of private financial savings or that they had come to certain market-sharing arrangements.

Changes in the Financial Environment

The UK financial system was quite well developed by 1880. Most of the currently operating institutional groups were established, and the Government had already passed most of the statutes which now form their legislative environment. Moreover, the authorities had already become directly involved in the market through the creation of their own savings-collecting agencies, and they had developed the two rationales on which the future State’s influence was based: stimulating and safeguarding low-income groups’ savings and manipulating the portfolio preferences of the financial institutions so that the State’s financial requirements might be more easily met.

The background

By 1880, the bulk of the statutory framework in which the UK banking system was to operate over the next eighty-two years had been formed. The Acts of 1826, 1833 and 1844 provided a large part of the framework for the subsequent rapid growth of deposit banking. In 1826 and 1833 stamp duties were imposed on bills of exchange written in amounts of less than £20 and £50 respectively. In addition, by the 1833 Act, joint-stock banks were permitted to operate in the London area providing that they refrained from issuing notes. These Acts, in conjunction with the Bank Act of 1844, which placed a rigid ceiling on all bank fiduciary note issues for the next seventy years, help to explain the subsequent expansion of the deposit-based joint-stock company banking system. Acceptable substitutes for deposits, small denomination bills of exchange or currency notes, were either heavily taxed or prevented from increasing by statute; whereas deposit-creating institutions received legislative stimulus.

Legislation in the 1850s and the 1860s further enhanced the growth of deposit banking. The usury laws were repealed; the stamp duty on bank cheques was reduced to 1d; the duty on internal bills of exchange was changed from a specific to an ad valorem tariff; severe penalties (transportation for life) were imposed for fraudulent cheque alterations, and, under the Companies Act of 1862, banks were accorded the privilege of limited liability. These developments coupled with the Bank of England’s entry into the London Clearing House in 1864 and its acceptance of its position as a lender of last resort after the Overend and Gurney crisis in 1866 bolstered the expansion of joint-stock bank deposit liabilities. The legal impediment to a rise in their earnings through interest-rate regulation had been removed. The tax on the utilization of their liabilities had been reduced. Both the State and the Central Bank had passed legislation or adopted procedures to foster public confidence in their liabilities. In the meanwhile the expansion of other competing media of exchange was constrained by the authorities. The banks had been given a near monopoly over the creation of the new additions to the money stock. They used it. Their combined deposits tripled between 1880 and 1913.

By 1880 much of the important capital market and institutional savings’ legislative framework had been set up too. The Company Acts of 1837, 1862 and 1867 broke the Crown’s monopoly over the control of the formation of joint-stock companies with limited liability; this form of business organization, as it became more extensively utilized, both increased the demand for and the ease of issuance of institutional loan accommodation.

The various Friendly Society Acts of 1793, 1829, 1836, 1842, 1846, 1850 and 1855, and the Trustee Savings Bank Acts of 1817, 1820, 1824, 1828, 1833, 1835, 1844, 1860, 1863, 1877 and 1880 established much of the legislative environment in which these charitable or non-profit organizations were to operate in subsequent years.

The Friendly Society Acts were designed to promote and protect the growth of small savings by providing both incentives and safeguards to such asset accumulations. The benefits paid by the Friendly Societies were exempted from taxation and their transactions were exempted from stamp duties. To acquire such benefits Friendly Societies were required to register with the newly established office of the Registrar of Friendly Societies and to file annual reports with that office.

The trustee savings banks received similar treatment. All the proceeds of their ordinary deposits were required to be lodged in the account of the National Debt Commissioners at the Bank of England. They were paid a subsidized rate of interest on these funds, which in turn they were required to pass on to their depositors after allowing for expenses. The subsidization of small savings was assured by limiting the per annum deposit in 1828 to £30 and the maximum deposit to £150 per depositor; these limits remained unchanged until 1893.

The legislative ground rules which the Government set up to govern the operation of its own savings bank in 1861 were similar. A maximum rate of interest on Post Office Savings Bank deposits of 2½ per cent was prescribed – it remained unchanged over the next hundred years. The maximum total and per annum placements of deposits per depositor were controlled (£150 total and £30 per annum). In the same way, the funds received on deposit were handed over to the National Debt Commissioners for investment, and, in turn, the Government guaranteed both the principal and interest earnings of such savings placements.

By 1880 then the State had passed the basic legislative statutes and established the administrative machinery to regulate the activities of most of the institutional participants in the small-savings movement; in addition, it had powers to direct the composition of some of these savings institutions’ investment placements and to regulate the means by which they competed for household savings. Only the statutory ground rules as they affected the building societies and the insurance companies had to be firmly framed.

The building societies were initially included under the Friendly Society legislation by the 1836 Act; however, the nature of their activities was such that they became subject to special legislation. By the Building Societies Act of 1874, they were allowed to incorporate; they were awarded limited borrowing powers of up to two-thirds of their outstanding mortgages, and they were prohibited from making property investments. Around the same time, the Treasury authorities began to reject the building societies’ claim for a tax exempt status under the 1829 Friendly Societies Act as many of them straddled the boundary between the charitable and private financial institutions due to their close connection with property companies. In 1894, however, the building societies’ position in the institutional savings structure was clearly delineated.

In the Building Societies Act of that year, the borrowing and investment powers incorporated in the 1874 Act were reiterated. In addition, the societies were prohibited from holding ballots for advances; they were required to furnish the Registrar of the Friendly Societies with an annual report which depicted all their property holdings, their past due mortgages, and all mortgage loans in excess of £5,000, and they were exempted from paying stamp duties. In the same year, the societies reached an agreement with the In...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Conent

- List of Tables

- List of Graphs

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Growth of UK Financial Institutions and Changes in the Financial Environment 1880-1962

- 2 The Growth of the UK Money Stock, Household Encashable Assets and Financial-Sector Credits by End Use 1880-1962

- 3 Asset Preferences and the Money Supply in the United Kingdom 1880-1962

- 4 Estimation of Income Velocity, Asset Preferences and the Supply of Selected Institutional Liabilities in the UK 1880-1962

- 5 Money, Encashable Assets, Private Institutional Credits and Private Expenditure in the UK 1880-196268

- 6 Conclusion: Some Historical Findings and Some Theoretical and Practical Implications

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index