This is a test

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of British Livestock Husbandry, to 1700

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 2005. This book is a history of the techniques of livestock husbandry in Britain and of the evolution of British breeds of domesticated animals of the farm. Adequate background on the business of buying and selling stock and of the influence of the market upon pastoral policy has been included throughout. As such, this title will be of use to new students and those with an existing background in the history British livestock husbandry.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A History of British Livestock Husbandry, to 1700 by Robert Trow-Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

5

THE LIVESTOCK TOPOGRAPHY OF

TUDOR AND STUART BRITAIN

TUDOR AND STUART BRITAIN

It is one of the commonplaces of the economic, social and literary history of Britain that the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were a period of transition from senile mediaevalism to a vigorous and adolescent modernity. This was true equally for agrarian methods and materials as it was for religious and polito-economic thought, for the English language, for English maritime expansion, and for the English landscape. On the land, the change from subsistence farming to a commercial agriculture was a result of many and complex factors, which have been fully stated and analysed by the economic historian. In the field of livestock husbandry, the motivating force was singular and simple: the demand made for meat and other livestock products by a rising population of townsmen who had neither the desire nor the opportunity to grow them for themselves. The coincidence of this great urban mouth with the accelerating breakdown of the feudal structure of land tenure, with the release of monastic land by the dissolution of the religious houses, with the consolidation of a rural class of yeomen which had been long in the making, and with the retirement to the countryside of the businessmen-turned-farmers who brought a new spirit of commercial exploitation to an old calling—this coincidence transformed both the cultivation of the soil and the management of the domestic animals of the farm from peasant arts into just one more aspect of the industrialism which was settling, firmly and irrevocably, upon the face of Britain.

In general, it is probably true to say that improvement in both the techniques and the stock of animal husbandry lagged behind the improvement of, and interest in, the cereal and other crops of the farm—despite the example by the religious and lay sheep-masters of what rationalization and intensification could here achieve; but, none the less, it was in this period of two centuries of Tudor and Stuart rule that the stockman ceased to be satisfied with the traditional methods of management and types of cattle, sheep, pigs and horses, and began to seek new ways of stock husbandry and new animals to use them upon. He was moved not only by the natural desire for a profit but also by a change in emphasis in the demand for his produce. Wool remained eminently saleable; but red meat, butter and cheese rose to at least economic equality with the golden fleece; and the stockman had to reorientate his management and his livestock accordingly. In these, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the cow became a breeder of meat and a giver of milk and began to lose its primary importance as a begetter of beast for traction; the carcase and the prolificacy of the sheep assumed equal importance with the quality and the quantity of its wool; the small mediaeval horse proved inadequate to the new place it was asked to fill on the land, on the road, and in the battlefield, and more power had to be bred into it; and the pig began to be more fully domesticated than it had been in its ancient half-wild state in the woods—but only slowly so.

The Topographical Sources

The documentary evidence for this gradual, little-chronicled but none the less decisive revolution in British livestock husbandry is scattered throughout the contemporary records; and it has to be assembled piece by piece. The rise of the native school of sixteenth and seventeenth century topographers—Leland and Camden, Aubrey and Martin and the rest—makes it possible, for the first time since 1086, for some regional survey of livestock husbandry to be made, fragmentary though it is; and the transcription and publication ofa small fraction of the great store of inventories permits some sort of quantitative analysis of density of stocking to be made from district to district. Yeomen’s and squires’ diaries and estate accounts indicate the beginnings of the division between the stock-breeder and the stock-feeder, and chronicle the rise of the great droving movement which brought Welsh and Scottish runts from their native hills to East Anglia and Kent for finishing for market. From the mass of estate surveys there emerges, for the first time, a satisfactorily complete picture of the common-field stint in operation. Records of tithe cases—an unaccountably little used source of agrarian history— farmers’ notebooks, and the more level-headed and earthy of the didactic writers enable the methods of stock management to be described in some detail. Material is becoming available from which the rise of the great urban meat markets can be followed. And, least satisfactory of all, port books, persistent tradition and contemporary authors’ asides hint at rather than document the fundamental amelioration of British breeds and types of livestock which imported blood was effecting. All in all, the resultant picture of British livestock husbandry in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries which can now be assembled presents a fairly complete and coherent scene, a little blurred though some of the details may be.

It may be most convenient first to assemble in this chapter the regional evidence upon the character, intensity and venues of the livestock husbandry of this period; and then, in the next chapter, to consider the general techniques of that husbandry.

South-West England

One of the earliest of the great county topographies was that written by Richard Carew of his native Cornwall. Unlike that of many other local surveys, his critical approach gives confidence in the accuracy of his observation. Cornish stock husbandry, when it emerges into history in this century, bears testimony to the remoteness of its provenance and the preoccupation of the inhabitants with the profitable tin-mining of the peninsula.1 The Cornish sheep, far from monastic influence except upon the eastern border neat Tavistock, were good bodied and coarsely fleeced with the ‘Cornish hair’ which was woven into the kerseys of the Bampton and Tiverton looms. They appear to have been medium long-wools, analogous to the unimproved Welsh sheep and to the extinct Scillonian breed. Tonkin, in his notes written about 1730, reported that there was a four-horned strain in the breed which was rapidly being eliminated by the selection of ‘bald’ sires and dams from which to breed for ease of lambing. This Cornish wool had been among the lowest priced in the mediaeval lists, and no evidence remains of any effort to improve it; but earliness of fleshing, size and prolificacy were all being inculcated into the sheep of Cornwall in Carew’s day by enclosure, pasture improvement and controlled stocking. These three factors—rapid finishing, weight and twinning—began to come into prominence throughout southern Britain at this time, with the decline of common gracing and overstating and the greater opportunities to grow better grass and the new fodder crops; but they were usually accompanied by a deterioration in the fineness of the staple, although more adequate winter feeding led to greater strength in the fibre. Fecundity in the Cornish sheep, indeed, improved so rapidly that in 1732-3 Joseph Nott of St. Gorran had nineteen Iambs out of nine Cornish ewes—eight sets of twins and one set of triplets.

9. The last of the makers of the great two-hundred weight Cheddar cheeses, Mr. F. L. Mabey of Castle Gary, with one of the smaller oak moulds which were used m his cheese rooms.

10. A Shetland “moorit” sheep with half its fleece shed, a characteristic of the unimproved and primitive breeds of the Welsh hills and the Scottish islands.

The Cornishman, said Carew, had little bread-corn, brewed a miserable ale, and lived largely on ‘milk, sour milk, cheese, curds, butter and such like as came from the cow and the ewe, who were tied by one leg at pasture’.2 These native cattle, kept mainly upon the moors, were stated to be black by Borlase, writing in a later century.3 The analogy between the principal livestock of Wales and Cornwall is worthy of note: its cause is irretrievably lost in prehistory, but may well have been associated with the megalithic immigrants from the south-west in the second millenium B.C. On the north-eastern border of Cornwall, however, adjacent to the great cattle region of Barnstaple, a large number of cattle were agisted for Devon breeders.

The general standard of sixteenth and seventeenth century livestock husbandry in Cornwall is summed up by Carew in his statement that some stock farmers ’suffer their beast to run wild in their woods and waste grounds, hunt them, and kill them with crossbows and pieces’. Here again, the same primitive method of ‘husbandry’ will be encountered in Wales.4 There was, however, some more normal stock-farming practised upon the Devon border within the aura of the civilizing influence of the port of Plymouth. Here, a generation after Carew wrote his depreciation of Cornish stockmen, John Eliot, ‘late Prisoner in the Tower’, left upon his death a normal seventeenth century English complement of domestic animals: three labouring horses, nineteen hogs and five ‘litle pigges’, forty young sheep and forty-five ewes and lambs, eight oxen [for the plow] four kine and two ‘heafers’,5 four 2-year-old bullocks, four yearlings and six rearing cows.6 His livestock were a considerable proportion of his total estate.

Plowing was done by oxen alone in both Cornwall and Devon at this time, and until very much later. The reason that horses were not used is probably that the West Country breeds were bred for nimbleness to negotiate the hillsides, and for pack or pannier transport, rather than for the weight and the tractive effort necessary to pull the massive wooden plow of the region. These small West Country pack and riding horses were called Goonhillies locally.*

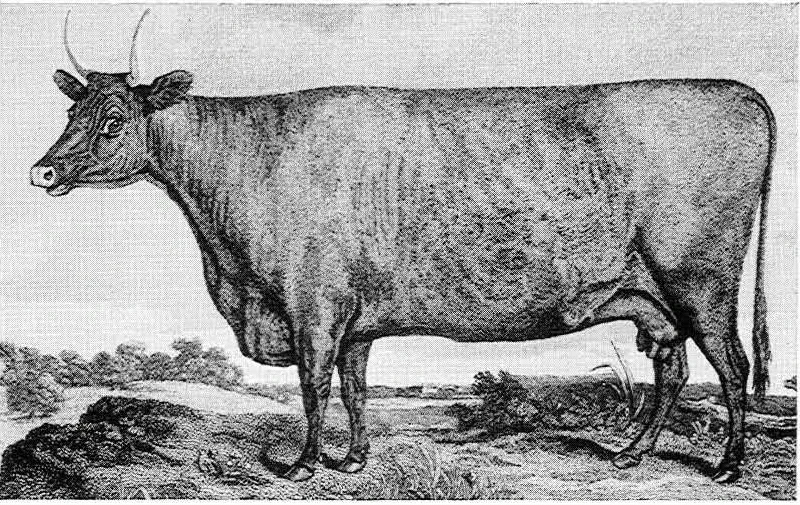

Devon had its own specific breeds, or types, of cattle and sheep. Of the cattle—the progenitors of the red Devons soon to come under the improving hand of the Quartleys—Risdon, who lived in the midst of their country at Great Torrington, wrote that they were ‘as good as any in the Kingdom’.7 No precise evidence can be produced for the existence of the Devons as a distinct breed before the eighteenth century; but the succession of circumstantial evidence for a concentration of cattle in north-west Devon, where the breed traditionally originated, from Domesday onwards can hardly be interpreted otherwise than as giving this stock an unbroken ancestry nearly as ancient as any among British bovine animals. They appear to have been relatively small in this period, for a much quoted provision by Elizabethan naval purveyors in Devon fixed the minimum weight of a fat ox at 6 cwt.8—presumably live weight—and this is about half the weight of a modern Devon of a comparable maturity, probably four to five years old. It was probably these Devons who Camden noted were summered upon Dartmoor. Tonkin also commented on ‘the forest of Dertmore [as] being 20 miles in length and 14 in breadth, and yielding pasture every summer to near 100,000 sheep’.9 The principal Tudor and Stuart breed of Devon sheep was the dun-faced nott, which Tonkin noted early in the eighteenth century as being also found in Cornwall, where they had reputedly been brought from the South Hams.10 By the beginning of the nineteenth century their entity was being smothered by the New Leicesters.

The sheep husbandry of Devon, substantial though it seems to have been, was overshadowed by the famous flocks of Dorset, where the chalk outliers of Salisbury Plain had been intensively sheeped from Roman times, and perhaps long before11 and which, as the plow spread on to the hills again, demanded the fertility and the treading of large flocks for the production of cereal crops. The Dorset monasteries entered in the Valor Eccksiastictts on the eve of the Dissolution alone possessed more than 2; ,000 sheep in the county.12 Leland noted large flocks on ‘the Dorset Heights’13 which, said Gerard in the first half of the seventeenth century, ‘much enricheth the owners, by selling their fleeces and lambes’.14

The stints on these Dorset hills in the mid-sixteenth century customaries indicate how numerous the sheep population was; Fussell comments that it must have been ‘very large’.15 Indeed, Leigh in 1659 wrote that it was commonly stated that ‘within 84 miles compasse round about Dorchester three hundred thousand sheep’ were to be found.16 As enclosure progressed in the sheltered and moister valley bottoms and as the practice of watering the meadows developed the Dorset flockmaster was placed in a very advantageous posit...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- PREHISTORIC AND ROMAN BRITAIN

- SAXON SETTLEMENT AND DOMESDAY SURVEY

- LIVESTOCK FARMING IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES

- MEDIAEVAL SHEEP HUSBANDRY

- THE LIVESTOCK TOPOGRAPHY OF TUDOR AND STUART BRITAIN

- THE TECHNIQUES OF THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES

- LIST OF PRINCIPAL SOURCES

- LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- INDEX