![]()

MICHAEL ARGYLE

Introduction

By socially skilled behaviour I mean social behaviour which is effective in realizing the goals of the interactor. These may be the professional goals of doctors, nurses and social workers, or of various kinds of interviewers, supervisors, chairmen, etc. as discussed in this book. In most of the chapters in this book the goals of particular skills are described. In some cases there are several different goals, which are not always compatible with each other. The goals may also include the personal goals of wanting to make friends and influence people in everyday life.

By comparing the styles of social behaviour of effective and ineffective performers it is possible to discover the kinds of social behaviour which lead to the desired results in particular settings, and thus constitute socially skilled behaviour. Many examples of such research, and of the styles of social behaviour shown to be most effective, will be given in later chapters. The effects of different styles of performance in attaining goals can be very great. Early research on supervisory skills, for example, found that supervisors who scored high in certain dimensions of supervisory skill produced one-fifth of the absenteeism and labour turnover of those low in such dimensions.

In this chapter I shall try to set out the main results of research into the basic processes used in skilled behaviour. This can open up new areas of research into more practical aspects of social competence. For example, research on the properties of interaction sequences may suggest new ways of looking at the behaviour of effective and ineffective performers, and hence at aspects of behaviour which could be made the focus of training. Examples are failures to handle conversational sequences and the structuring of such sequences by skilled performers (p. 173).

The social skill model

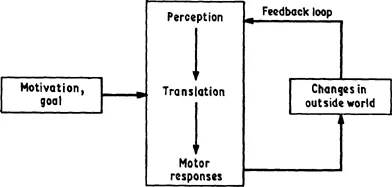

This model draws attention to a number of analogies between social performance and the performance of motor skills like driving a car (see Fig. 1.1). In each case the performer pursues certain goals, makes continuous response to feedback and emits hierarchically-organized motor responses. This model has been heuristically very useful in drawing attention to the importance of feedback, and hence to gaze; it also suggests a number of different ways in which social performances can fail and the training procedures that may be effective, through analogy with motor skills training (Argyle and Kendon 1967, Argyle 1969).

Figure 1.1 The social skill model (from Argyle 1967).

The model emphasizes the motivation, goals and plans of inter-actors. It is postulated that every interactor is trying to achieve some goal, whether he is aware of it or not. These goals may be to get another person to like him, to obtain or convey information, to modify the other's emotional state, and so on. Such goals may be linked to more basic motivational systems. Goals have sub-goals: for example a doctor must diagnose the patient's disease before he can treat him. Patterns of response are directed towards goals and sub-goals, and have a hierarchical structure – large units of behaviour are composed of smaller ones, and at the lowest levels these are habitual and automatic.

Harré and Secord (1972) have argued persuasively that much human social behaviour is the result of conscious planning, often in words, with full regard for the complex meanings of behaviour and the rules of situations. This is an important correction to earlier social psychological views, which often failed to recognize the complexity of individual planning and the different meanings which may be given to stimuli, for example in laboratory experiments, However, it must be recognized that much social behaviour is not planned in this way: the smaller elements of behaviour and longer automatic sequences are outside conscious awareness – though it is possible to attend, for example, to patterns of gaze, shifts of orientation or the latent meanings of utterances. The social skills model, in emphasizing the hierarchical structure of social performance, can incorporate both kinds of behaviour. There is another important implication of this line of thought: the moves, or social acts, made in social behaviour are rather different from the actions in a motor skill. Social acts, like shaking hands, bidding at an auction sale or asking questions at a seminar are signals with a shared social meaning in a given context. They are like the moves in a game: in any particular game there is a repertoire of possible moves, which is quite different for chess, polo or wrestling; each move has a generally accepted meaning in the context of the game and the move can be made by alternative physical actions.

The social skill model also emphasizes feedback processes. A person driving a car sees at once when it is going in the wrong direction, and takes corrective action with the steering wheel. Social interactors do likewise; if another person is talking too much they interrupt, ask closed questions or no questions and look less interested in what he has to say. Feedback requires perception, looking at and listening to the other person. Skilled performance requires the ability to take the appropriate corrective action referred to as ‘translation’ in the model – not everyone knows that open-ended questions make people talk more and closed questions make them talk less. It also depends on a number of two-step sequences of social behaviour whereby certain social acts have reliable effects on another. The social skills which are most effective vary with the situation, and also with culture and social class. Cultural differences in social behaviour are described in Argyle (ed.) (1981). Shure (Chapter 6) describes how to train people in a problem-solving approach to difficult social situations, whereby they are encouraged to engage in ‘means–ends thinking’. Maladjusted adolescents were less able than controls to formulate a step-by-step plan to deal with situations. In the selection interview various kinds of difficult candidates must be dealt with and interviewers can be taught the special skills needed for each. The ‘translation’ part of the model often includes complex cognitive structures, including the rules and other features of the immediate situation and knowledge of social processes (Pendleton and Furnham 1980).

It is an interactor's behaviour which affects other people, but the model also applies to the control of thought and feelings. Hochschild (1979) has argued that social skills performers, especially those in professional roles, are expected to have the right feelings – to be happy, sad, grateful, etc. where appropriate.

The role of reinforcement

This is one of the key processes in social skill sequences. When interactor A does what B wants him to do, B is pleased and sends immediate and spontaneous reinforcements – smile, gaze, approving noises, etc. – and modifies A's behaviour, probably by operant conditioning, for example by modifying the content of A's utterances (Rosenfeld 1978). At the same time A is modifying B's behaviour in exactly the same way. These effects appear to be mainly outside the focus of conscious attention and take place very rapidly. It follows that anyone who gives strong rewards and punishments in the course of interaction will be able to modify the behaviour of others in the desired direction. In addition, the stronger the rewards that A issues, the more strongly other people will be attracted to him.

The role of gaze in social skills

The social skill model suggests that the monitoring of another's reactions is an essential part of social performance. The other's verbal signals are mainly heard, but his non-verbal (NV) signals are mainly seen – the exceptions being the NV aspects of speech and touch. It was this implication of the social skill model which directed the study of gaze in social interaction. In dyadic interaction each person looks about 50 per cent of the time, mutual gaze occupies 25 per cent of the time, looking while listening occurs about twice as long as looking while talking, glances are about 3 seconds, and mutual glances about 21 seconds, with wide variations due to distance, sex combinations and personality (Argyle and Cook 1976).

Differences between social behaviour and motor skills

Rules The moves which interactors may make are governed by rules; they must respond properly to what has gone before. Similarly, rules govern the other's responses and can be used to influence his behaviour, e.g. questions lead to answers.

Taking the role of the other It is important to perceive accurately the reactions of others, and the perceptions of others – i.e. their point of view – must also be perceived. This appears to be a cognitive ability which develops with age (Flavell 1968), but which may fail to develop properly. Those who are able to do this have been found to be more effective at a number of social tasks and more altruistic. Shure (Chapter 6) describes how to train parents and children in recognizing the points of view of other people in difficult situations.

The independent initiative of others Other interactors are also pursuing their goals, reacting to feedback and so on. The social skills model itself deals with one inter actor at a time; to deal with sequences of social interaction further concepts must be introduced. I shall discuss below the ways of analysing these sequences of interaction. The social skill model fits best cases of ‘asymmetrical contingency’ (interviewing, teaching, etc.), where one person is more or less in charge. In such cases the social skills used by effective and less effective performers may be compared. On the other hand, in negotiation both sides have a similar degree of initiative.

The psychology of the other While cars and typewriters behave in accordance with...