![]()

It was just past one o’clock on an ordinary hot and sunny Friday afternoon at the end of August in 2003 when I first walked into Riverside Mosque, a square, two-story yellow brick building topped with a green dome, adjacent to a Christian Reformed Church and an elementary school affiliated with the church, in a quiet neighborhood near one of the busiest roads in the city of Riverside. With neither a pair of the distinctive minarets1 that adorn the majority of mosques around the world, nor a sign board declaring the affiliation of this congregation, Riverside Mosque was no more striking than most other places of worship across the town. In fact, even many of the Muslims who were new to this area would easily pass it as one of the many churches in town. At the time I did not know if this religiously generic façade was a deliberate strategy to keep the community from unwanted and negative attention or if perhaps the architect’s personal plan was to blend the mosque into the local landscape. Nevertheless, although the building might not be very eye-catching, it was probably striking for those passing by the building at this hour on a Friday afternoon to see people dressed differently than ordinary Americans rushing into the building.

I was new to the city of Riverside and had just made some Muslim friends through a college orientation program. Muhammad, a graduate student who was studying at one of the universities in the city, offered to take several newcomers to attend Jummah in Riverside Mosque, the largest mosque in the area.2 When we drove into the parking lot, it was already crowded with dozens of cars and vans. Men and women dressed in various styles of clothes hurried into the building. Their clothing was so diverse that it seemed like a multi-cultural fashion exhibition. The conservative dress of the women set them apart from Americans in general. Although it was a hot summer day, none of the women wore short-sleeve shirts, short pants, or short skirts. Some women were dressed in jilbab or abaya,3 others wore salwar kameez,4 some were dressed in colorful African robes; while some others wore Western-style jeans/pants/ankle-length skirts and blouses. Regardless of what the women were dressed in, each had covered her hair with hijab,5 which again had a variety of styles and colors. Some women strictly covered their hair, ears, and necks; while others just loosely wrapped their heads with thin silky scarves. Suits were not the popular clothing among men at this hour. Instead, some of the men wore traditional salwar kameez, usually white, and small white kufi caps;6 some wore colorful African robes; while many others, especially young men and boys, were dressed in casual clothes, even baggy jeans or shorts and T-shirts. Quite a few men in medical staff’s blue or green uniforms had apparently just come from work and had to return soon after the prayers.

The small paved parking lot was full. We joined some cars parked on the unpaved ground. Muhammad told us that Riverside Mosque was a largely Sunni Islam immigrant mosque accommodating Muslims of different races and ethnicities, such as South Asian, Arab, Bosnian, Iranian, Turkish, Central Asian, African, African American, Southeast Asian, and White living in the surrounding areas. Established in 1994 when the Muslim population in town was small, the mosque had outgrown its accommodation capacity. Words had been going around that the Mosque Executive Board would soon begin a mosque expansion project. In the near future a community hall and playground for children would appear on the unpaved part of the parking lot where we had left our car.

The mid-summer heat was scorching. We got out of the car, walked quickly toward the air-conditioned building, and entered through the door on the ground level. Compared to many of the mosques I had visited before, Riverside Mosque was somewhat “strange”—men and women shared the same entrance. “As-salaam Aleikum (Peace be upon you),” several men with distinctive South Asian and Arab facial characteristics and two black men at the door taking off their shoes sensed the coming of people, quickly raised their heads and greeted us with smiles as we entered. “Waleikum as-salaam (Peace be upon you too),” we replied and smiled. They seemed quite used to women’s presence in the mosque and were not bothered by us entering the door.

I felt as if I had just entered an ordinary home. There was no such awed feeling as I had when I first entered a Basilica two miles away from the mosque. It was not so much because of the humble interior decoration compared to the grand Basilica adorned with splashes of gold, but probably because the hall was not decorated with anything that carried sacred or religious meanings. Only a simple poster of the Dome of the Rock Mosque in Jerusalem and a handful of educational posters on Islam scattered on the walls revealed the identity of this house and those who gathered inside.

Several long, folding plastic dining tables stretched out in the rectangular dining area to the right. Behind the serving counter across from the door was a mid-sized kitchen clustered with stoves, sinks, oak cabinets, a refrigerator, and a center island, where a middle-aged South Asian woman was busy transferring food to Styrofoam boxes from several big metal pots and disposable aluminum pans. She greeted us, and we returned greetings. “This is Aunty Reena, the nicest person in the community,” Muhammad introduced her. Reena smiled at this comment and welcomed us with warm hugs. Her smile was sincere and pleasant. Reena told us that if we had not eaten, we should each take a box before leaving. She said, “This is usually for five dollars each, but I’ll give it to you for free if we have enough.” Muhammad told us that the food was donated by local Muslim families to raise funds for mosque maintenance and other expenses. We happily accepted her offer and said “salaam (peace)” to her as the equivalent of “see you later.”

Figure 1.1 Riverside Mosque floor plan.

We took off our shoes and searched for spots to place them, as the floor at the entrance was heavily cluttered by unorganized shoes of all kinds and sizes. I was not surprised by this untidiness because I had seen this scene in other mosques as well. As we climbed the stairs, a few more women entered through the same door we had just come through, exchanging greetings with each other. At the top of two flights of stairs was the prayer hall. A donation box and several piles of booklets and printouts in various sizes were spread out on two tables against the wall to the right. At the far end of the hall, an Imam in a white robe and white kufi, standing in front of the mihrab (prayer niche) next to the minbar (pulpit or stage), was delivering khutba or sermon in English with a distinctive Urdu/Hindi accent. He was speaking about a hadith (prophet’s words and behaviors) and explaining how Muslims should learn from this hadith and apply it to their everyday lives in this world.

The boiling heat had vanished completely. The prayer hall seemed spacious under the dome and was lit brightly by the sunshine cast through the windows. Screens on the far left end delineated a separate prayer area for women. I saw roughly fifty men as I glanced toward the men’s prayer area. Some people were standing offering prayers, two elderly men were sitting in chairs, while everyone else was simply sitting on the carpet, concentrating and listening. Three women were sitting by a rectangular table behind the men against the wall. There was no screen keeping them from seeing the Imam—another interesting discovery about this mosque. As I passed by, we smiled at each other and exchanged greetings. All three of them were fair-skinned, but I could not tell their ethnicities without speaking to them. One woman was probably in her sixties, while the other two were probably in their forties or early fifties.

Instead of joining them, I walked toward the screen. I knew I would see more women on the other side of the screen like I would in a typical mosque in this country. Indeed, the dark pink mobile panels standing on the left hand corner of the prayer hall marked out a small area—about one-fifth of the prayer hall—for women to listen to the khutba and perform ritual prayers. Behind the screen, around ten women and several teenage girls were either sitting on the carpet or offering prayers. Several toddlers and young children—both boys and girls—were playing around their mothers. Gender segregation in Muslim societies is not anything new. But gender division in mosques did not become a big issue until they were transplanted to Western soil. Since women are not required by the religion to pray in mosque, it has become a norm for women to pray at home, given women’s traditional roles that are tied to the households. Many women in Muslim countries have never set foot in a mosque. However, unprecedentedly, more and more immigrant Muslim women in the United States are now attending mosques on a regular basis. In addition, Western converts to Islam often actively participate in mosque activities and affairs. For female converts, attending mosque is an important way to maintain their newly found faith and it naturally becomes part of their weekly routine. The gendered spatial arrangements within mosques in the West have not only been a major target of Western media, politicians, and scholars, but are also contested among Muslims themselves, especially women. People from different backgrounds come to different understandings of gender relations in Islam. However, I was still surprised by the existence of the two sitting areas for women in Riverside Mosque.

As I walked toward women’s prayer area, I also noticed that the mosque’s designer had made a smart use of geographical characteristics to facilitate gender divisions. Since half of the Mosque was built on the hill and half on the ground, the architect had placed a door on the hill side facing the passing traffic, while placing the other door on the ground level facing the parking lot. The women’s prayer area was close to the hill-side door, while the men’s section was close to the stairs that lead to the ground level entrance/exit. The two doors made it convenient to practice gender division. This design allows women to enter and exit the mosque with minimum interactions with men. However, the door on the ground level also leads to the kitchen—traditionally women’s territory—dining area, and restrooms. Therefore, entering the mosque from the ground level was not abnormal for women, as I discovered when I entered and received friendly greetings from the men. It seemed to me that in this mosque, women had the option of whether or not to adhere strictly to the “screen rule.” It also seemed that this arrangement came out of some kind of compromise, given that gender division is the norm in Muslim societies.

I picked a corner at the back and sat down on the carpet against the wall so that I did not have to walk in front of women who were offering prayers. I could tell the adults and teenagers were mostly Arabs, South Asians, Blacks, and Whites. These women were quietly listening to the sermon most of the time. But once in a while, a couple of them would turn around and whisper something into each other’s ear. Although people were expected not to talk to each other during the time of khutba, women sitting behind the screen were apparently less compliant. Young children were playing around their mothers. Some were busy with their toys muttering baby words, while others were not so obedient. Several boys were chasing each other and making funny noises. Their mothers had to take them out of the prayer area a few times to stop them from disturbing others. When hearing the adan (call for prayer), the women sitting in the two different areas all stood up and converged into rows behind the screens, shoulder to shoulder to perform salat (Muslim prayer), which ended the Friday Jummah prayer. Once they had completed their prayers, the people stood up and greeted each other with hugs and kisses on both cheeks. Some left in a hurry, but many stayed to chat and catch up with people they rarely met outside the mosque.

This was my first encounter with Muslims in Riverside who gathered for the weekly religious ritual that day, but studying this group of people tied to the two-story building—many of whom I later became friends with—was not on my mind at that time. The more time I spent with the people of Riverside Mosque, the more I wanted to analyze their stories through the eyes of a sociologist who is intrigued by the role religion plays in immigrants’ adaptation to American society. My journey with the Riverside Muslim community started that sunny Friday afternoon and eventually developed into this three-year ethnographic study. The glimpse that I caught of the mosque and its people during my first visit would later become important themes in my research. The racial and ethnic diversity of members and the loosely maintained gender segregation have an important impact on the intergroup relations within the mosque, which will be elucidated in the following chapters. Before embarking on any further analysis, I now turn to a brief introduction of the city of Riverside and the history of its Muslim residents, Islamic centers, and mosques.

THE CITY OF RIVERSIDE AND ITS MUSLIM RESIDENTS

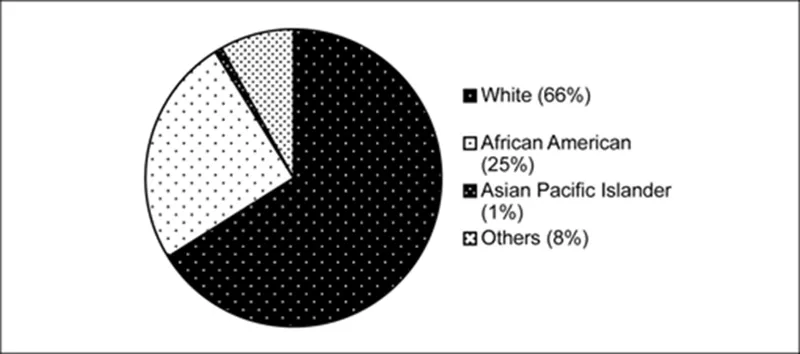

Riverside, a mid-sized city in the heart of the United States, is the home of more than two hundred Muslim families, many of whom are involved in this study. The total residential population of the city of Riverside and its immediate vicinities reached around 200,000 at the time of my study. About half of that population, just under 110,000 people, resided in the city of Riverside. Among them, 65 percent were White; 25 percent were African American; 1 percent were Asian and Pacific Islander; and 8 percent were Native American, mixed, and other races. Hispanics/Latinos of any race were 8.5percent of the total population (See Figure 1.2).7 The median household income of Riverside in 2000 was less than $33,000, and per capita income was about $17,000.8 The state itself stood somewhere in the middle among the fifty U.S. states in terms of its median income between the years 2003 and 2005.9 Most low-income Riversiders, disproportionately African American and Latino, resided in the west side of the city; whereas the majority of middle and upper-middle class residents, usually White and Asian, tended to purchase their homes in the quiet outskirts north of the city or around the up and coming business center south of the city. The Latino population has been increasing steadily in recent years, forming some predominately Latino neighborhoods dotted across the city premise.

Figure 1.2 Basic demographic characteristics of Riverside.

Built in the nineteenth century, Riverside flourished as it became home to several large industrial manufacturers and higher educational institutions. Its geographic proximity to Detroit and Chicago, the two automotive manufacturing centers at that time, granted it the opportunity to prosper from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century. However, like many other industrial cities of its time, Riverside endured the consequences of the decline in the manufacturing industry nationwide. The dams on the river that runs through Riverside and the abandoned factories south of downtown are the only reminders of the city’s glorious past during the Industrial Age. Riverside’s economy is now sustained largely by education and health care. Its universities, hospitals, clinics, and laboratory facilities are attractive to highly-skilled immigrants.

Religion is an important element in people’s life in Riverside. The residents have established numerous places for worship and formed various religious organizations. In addition to more than fifty churches of a variety of Christian denominations and national origins, there are also three Synagogues and five Islamic centers and mosques. Among the higher education institutions and schools in Riverside and surrounding areas, quite a few were founded by religious institutions. Given the influence of religious organizations, Riverside is also one of the major destinations of refugees and asylum seekers from war-torn regions in Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere. A steady influx of r...