This is a test

- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Corporate Financial Reporting in a Competitive Economy (RLE Accounting)

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is concerned with the financial accounting and reporting of publicly owned corporations to their shareholders. It examines the origins of financial accounting and reporting, external influences on accounting and reporting practices as well as the measurement process.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Corporate Financial Reporting in a Competitive Economy (RLE Accounting) by Herman Bevis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Accounting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

V

The Measurement Process: Accounting for Repetitive Operations

Considering the magnitude and long-range nature of many of the corporation’s commitments, and also the stockholder’s interest in reports of its periodic income, the central problem of corporate accounting is the measurement of revenues and expenses for short periods of time. To meet this problem in connection with repetitive transactions and events, there have been developed out of long experience four general guides to assist in making decisions: the transaction guideline, the matching guideline, the systematic and rational guideline, and the nondistortion guideline. The application of these to major classes of revenue and expense shows that often judgment is involved in giving one more weight than another. Consistency in measurement method and technique is of great importance.

The preceding chapters have uncovered a number of needs and influences to which financial accounting and reporting should be responsive. This chapter deals with responsiveness to those needs and influences in terms of accounting guidelines and practices in the measurement process.

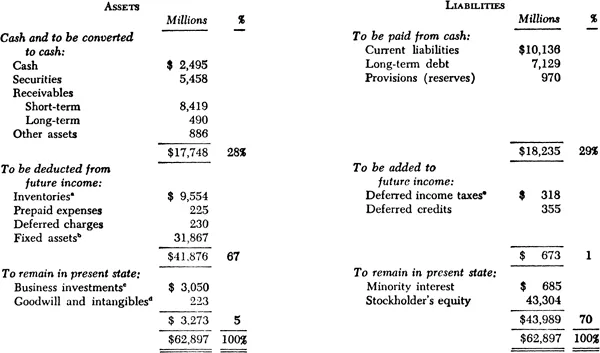

The distinct interest of the stockholder in the corporation’s periodic net income has been discussed. Essentially, this makes the central measurement problem within the accounting function the assignment of a corporation’s revenues, costs, gains, and losses to a given year. Some idea of the magnitude of the problem may be obtained by looking at the statement of financial position of the hundred large industrial corporations in the Appendix. The various items may be regrouped according to whether the next step regarding them is normally direct conversion to cash, or amortization as charges or credits in the income statement, as seen in the table on the opposite page.

Note that two-thirds of the items on the asset side of the balance sheet—some $42 billion out of a total of $63 billion—are not assets in the sense of either being or expected to be directly converted to cash. They represent a huge amount of “deferred costs,” mostly past cash expenditures, which are to be included as costs in future income statements. They are equivalent to nine years’ net income at the current rate of the hundred large industrial corporations referred to in the Appendix. Among all the footnotes explaining and elaborating on the income statement, this makes the balance sheet the biggest footnote of all. In contrast to the importance of deferred costs, it will be observed from the above summary that deferred credits in the balance sheet are not large, either in relation to other amounts in the balance sheet or amounts in the income statement. This contrast highlights the fact that the apportioning of costs among several years is a much greater problem than that of apportioning credits.

The above-described items of deferred costs and deferred credits in the balance sheet arise from the use of the accrual basis of accounting. As stated in Chapter II, this approach is to be contrasted with the cash basis of reporting. To repeat, the accrual basis attempts to transfer the income and expense effect of cash receipts and disbursements, other transactions, and other events from the year in which they arise to the year or years to which they more rationally relate. The cash basis treats them as income or expenses when they arise.1

________

a For some portion the classification is near “to be converted to cash,” but a step of deriving revenue from a sale intervenes.

b Includes land which will not be deducted from future income. Amount not available, believed minimal.

c Some portion could be converted to cash or deducted from future income.

d Some is being deducted from income, but the portion is not readily ascertainable.

e A portion not determinable but perhaps large may be assignable to the section “to remain in present state.”

The accrual basis reflects the fact that the corporation’s activities progress much more evenly over the years than its cash outflow and inflow. It avoids the haphazard distortions of net income by years which would result if the cash basis were used and, say, the entire cost of each manufacturing plant were considered an expense of the year it was acquired, even though it would be used for many years, or build-ups of inventory were treated as an expense this year rather than the next, in which they are sold. The accrual basis is not applied in practice as extensively as pure theory would suggest, however. As will be seen, the theory continually runs afoul of limitations on the ability to predict the future—to foresee, for example, whether this year’s expenditures that should benefit the future actually will and, if so, by how much. In spite of these limitations, however, the accrual basis of accounting stands always as an indispensable enabling authority for avoiding the reporting of distortions in year-to-year corporate income, when the facts are that a corporation’s activities and operating results progress more evenly than its cash transactions would indicate.

General Guidelines for Allocating Revenues and Expenses to Periods

The theory of the accrual basis of accounting is too general to provide a basis for making decisions in many situations.

Further guidelines are needed in practice. Also, the uncertainties of the future sometimes render the usefulness of applying the theory nebulous, if not doubtful, thus further emphasizing the need for guidelines.

THE TRANSACTION GUIDELINE

Record the effect on net income of transactions and events in the period in which they arise unless there is justification for recording them in some other period or periods.

In the application of the accrual basis of accounting, actual experience indicates that a majority of the items of income and expense are recorded as such in the year of the relevant cash receipts and disbursements. For example, a comparison of the revenues of $67.3 billion of the hundred large industrial corporations in the Appendix with $8.4 billion in accounts receivable at the year’s end, suggests that some seven-eighths of the reported revenues were represented by sales both effected and collected during the year. Of the total costs and expenses of S62.6 billion, the indication is that approximately 80 per cent were established by cash expenditures or current liabilities during the year.

It is instructive to pursue further the analysis of the data for the hundred corporations to estimate the revenues, expenses, and net profit that would have resulted if a strict cash basis had been used. This would have required all expenditures for inventories, fixed assets, and the like to be expensed immediately and revenues to be measured by cash collections on sales. On the cash basis, revenues and total costs and expenses would not have varied by more than 1 to 2 percent. However, the leverage would have produced a much sharper change on the residual net income figure. Individual companies would, of course, show divergencies of different magnitudes.

The foregoing indicates that a high percentage of business transactions are reported as revenues or expenses in the income statement at the time of the cash transactions, or near that point in time. True, many sales or purchases are on credit, but most of these are near to the cash receipt or disbursement—near in the sense that the collection of the receivable or the liquidation of the obligation occurs well within the conventional accounting period of one year. The income statement, then, starts out by largely reflecting transactions, and this means, predominantly, cash transactions. At the same time, the analysis of the data from the hundred corporations indicates that there can be a sharp difference in net income for as short a period as one year through departing from the transactions in applying the accrual basis of accounting.

What this amounts to is that financial accounting, in recording the progress of the corporation, looks for objective evidence of that progress. The most emphatic evidence which it can obtain that the corporation has earned revenues, for example, is to observe that it has received cash from an outside party in payment of products delivered or services rendered. But if the corporation has received only a promise to pay, rather than cash, financial accounting must set about to assess the probability that the cash will ultimately be received. Accrual accounting will permit the corporation to report that it has earned revenues upon the delivery and acceptance of the product or services if the credit term is short and the credit experience with the customer is good.

However, if experience and prospects suggest that only 99.5 per cent of the customers’ promises to pay will be received in cash, then this phase of accrual accounting gives way to the cash basis and admonishes that the 0.5 per cent should not be recognized as corporation revenues unless and until all collections are made. The longer the deferral of the cash receipt from the point of sale, the more the dimension of time introduces uncertainties. For example, assume that a significant portion of a corporation’s operations consists of 20-year installment sales of real estate, that risks are not widely spread, and that the corporation has no long-term collection experience. Under these circumstances, even though the corporation had completed its operating cycle when the agreements were signed with the customer, the accrual of profit at the time of sale would probably give way to the reporting of income on the practical cash basis of realization—the actual collection of the installments.

The tug of war between the accrual basis of accounting and the cash transaction works the same way, in reverse, on corporation costs. Whether an expenditure be for inventories, investments, deferred charges, research and development, fixed assets, or the like, the cash disbursement ordinarily precedes the expected benefit. The objective evidence is that disbursements of cash have been made for materials, labor, or services which sooner or later are unquestionably to be charges against the income of the corporation. The question is, income-charge now or later? Since the corporation has already given up some of its resources by the disbursement of its cash (which is objective evidence that it may have incurred a current cost), the pressure becomes strong to demonstrate why and how the expenditure will be a benefit to future years rather than a charge against the present.

The accrual basis of accounting, as well as other specific guidelines discussed below, provides ample justification in practice for reporting cost incidence not in the year of the cash disbursement but in the years of benefit. The alternative guidelines also provide for anticipating future cash disbursements in respect of current costs, such as services being received now which are to be paid for later.

The foregoing discussion has centered on transactions. Financial events that are not transactions also must receive accounting recognition at some point in time, either at the point of the event or at some other appropriate time. A catastrophe causing damage or the signing of an agreement settling a claim are events which, like the transaction, call for an appropriate accounting when they happen, unless the burden is borne of justifying an accounting for them in other periods.

THE MATCHING GUIDELINE

Where a direct relationship between the two exists, match costs with revenues.

One guideline which is highly persuasive in departing from the transaction guideline is that of matching revenues with related costs and reporting them in the same year. The application of the guideline is clearly seen in a merchandising operation, where merchandise is purchased this year but not sold until the next. The carrying forward of the inventory of unsold merchandise so as to offset its cost against the revenue from its sale is clearly useful in determining the net income of each of the two years. Numerous other related events can be, and are, matched in business experience. For example, the effecting of a sale can be matched with a liability to pay a sales commission.

Although there are cases in which the matching guideline is clearly useful, its application is much more restricted than one might think. It must be remembered that matching attempts to make a direct association of costs with revenues. The ordinary business operation is so complex that revenues are the end product of a variety of corporate activities, often over long periods of time; objective evidence is lacking to connect the cost of most of the activities with any particular revenues.

The matching guideline is sometimes confused with the allocation of costs to periods. Taxes, insurance, or rent, for example, may be paid in advance and properly allocated to the years covered. However, this allocation is to a period, and one would be hard pressed to establish any direct connection between—i.e., to match—these costs and specific sales of the period to which they are allocated.

Even with respect to inventories (the best illustration of the usefulness of the matching guideline) some costing methods tend to dilute the purity of the approach. Thus, while from the standpoint of the physical movement of most products or merchandise it is usual for the oldest items to be sold first, the “last-in, first-out” inventory costing method will offset against a sale the cost of the last item added to inventory. If LIFO has been in effect for 20 years, the costs of the items in this year’s inventory may be those of items acquired 20 years ago—and, physically, long since gone.

The matching guideline, so highly persuasive as virtually to be controlling when an objective basis for it exists, is, as a basis of apportioning revenues and costs among periods of time, limited in practice to relatively few types of items. The matching guideline can become potentially dangerous when it attempts to match today’s real costs with hopes of tomorrow’s ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Forces and Needs Underlying Corporate Financial Reporting

- How Corporate Financial Reporting Responds to the Forces and Needs

- The People Involved

- Summary

- Appendix

- Index