![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

A Mammoth Achievement

Over the first six decades of the twentieth century, councils all across Britain spent enormous amounts of time, effort and money building a new and optimistic form of housing – the cottage estates of ‘corporation suburbia’. Drawing on the models of garden cities and garden suburbs, by the early 1960s they had provided family homes with gardens for some 3 million mainly working-class households. It was a mammoth achievement. Some of the places it produced are of great character and quality.

Because of what then happened to council housing over the later years of the century, this is not very often appreciated. This book looks at that achievement to try and understand how these places work today. It also seeks to work out how the people who live there now, and the communities they are part of, can get the most out of this impressive inheritance.

The last few years have seen a lot of talk about planning new garden cities and suburbs. It seems like a good time to explore the potential of the garden suburbs we have already got.

This Book, and Our Questions

The genesis of this book lay in questions and ideas that came up during research about the links between housing and the economy in the three regions of Northern England.1 Dozens of localities were studied, across the North from Hull to Blackpool and from Tyneside to Merseyside. Eight of them, studied in some detail, were what were airily called ‘type 2’ areas: ‘near-market municipally-built’ suburbs – the familiar suburban council estates which are in or near every town and city in the country (Urban Studio, 2009a).

And the question that kept nagging was: these are (usually) well-built houses, on (generally) biggish plots, often with pleasant views out to the Pennines or the North Sea – why does it seem as though people do not choose to live here, what is it that does not work, and is it fixable? Lynsey Hanley, in Estates, nails it as usual: ‘There has to be some reason why people who waited years for a coveted home from ‘the Corpy’ wouldn’t wish the same for their own grandchildren’ (Hanley, 2007).

Coupled with that was the sense that these places might be something of a ‘lazy asset’ for their areas and communities. We do not seem to be getting the most out of them, socially or economically. In some of them, maybe many, there are of course deep-seated problems, and attitudes, to tackle. But the idea was about missed potential, not simply glum failure, and the wish now is to explore that potential and not just once again revisit the estates wearing problem-shaped lenses.

When I were a Lad…

This is not just academic. It is also about the shared experience of the post-war years. Growing up in Lancashire in the 1950s, your schoolmates were as likely to be from the – fairly recently built – estate as from the private housing in the surrounding roads and lanes. What stigma there was probably attached itself to the visibly poorer and scruffier little terraced streets and – especially – back courts as yet untouched by ‘slum clearance’. And mums on the estate were just as insistent on hankies and proper shoes (not tatty plimsolls) as any in the private semis. The separations that undoubtedly came later were associated with 16+ choices (work vs university, going away vs staying), by aspirations and class, as much as or more than by where you lived. Maybe, already, the distinction between Alma Hill (built to house ‘slum dwellers’) and Hall Green (the bigger town expansion to house the more respectable working-class) lurked somewhere there. However, the label of council tenant was not the key to that, or to our attitudes and experience in general. The estate was different, but it wasn’t that different, and it wasn’t stigmatized.

And indeed the literature from those years has almost as a trope the provincial working-class boy from the estate who looks back on those years, perhaps with a nostalgic glow. Yet his angst and regret are not noticeably tinged with a feeling that his home, or his estate, was the distinguishing feature of growing up – or of the life later exchanged for metropolitan excitements. Growing up on a cottage estate might end up with you up and out. But it was up and out from Wigan, not especially from those streets, that estate.

So there are questions here about the past of corporation suburbia, about what happened and why, which might help to inform what could happen in future.

A Starting-Point

The study in the North suggested that the opportunity for these localities could be of three kinds. First, they are still, a lot of them, council housing: they can – and should – remain areas of choice for people in the social-rented market. Second, alongside that, a stepping-stone role: they might be able to help meet growing demand for houses in the ‘intermediate’ housing market (for sale, but not full market pricing). And third, as houses are bought and sold: they ought to be able to integrate more fully into the ‘regular’ housing market around them. The aim would be for them ‘to become a place where households wish to stay given the means, as opposed to leaving as soon as they get a chance’ (Urban Studio, 2009a).

This in turn could change how they ‘work’ in another way: areas of choice, well-placed for access to jobs in the cities, they could play new roles in the labour market, for a wider range of working families.

People, Houses and Places

So the interest is partly about the issues of ‘mix’ and tenure change in these estates, where guidance has pre-eminently come from the work of Alan Murie and Colin Jones on the processes and effects of the ‘Right to Buy’ (Jones and Murie, 2005). It is partly about the areas’ roles in the labour and housing markets, and how these might change. And it is, inevitably, partly about some deep-seated problems which, it must be recognized, are not all confined to the inner-city tower blocks, as is clear from, for example, Lynsey Hanley’s analysis of her native outer-suburban Chelmsley Wood. But, and to stress: it is also about the potentials that one might be trying to release, and the positive side of the story.

‘Corporation Suburbia’

So the focus is on the ‘corporation suburbs’, as Richard Turkington labelled this form of housing in his work in the 1990s: the council-built estates, almost always in a ‘cottage’ format even if some flats are included in amongst the houses (Turkington, 1999). They are generally the ones that are not so stereotypically ‘problem estates’. The interest is in the ones that ‘work’, or could do so: their potential, and the threats they face. The thinking seeks to go beyond labels like ‘sink estate’, or ‘edge city’. These are not just pejorative – they are too simplistic to describe all our municipally-built environments.

Places that Work?

The case here is that making the most of the assets which this housing offers is a positive story. It can be positive for housing policy; for councils and their ‘place-making’ endeavours; and for the residents of the estates. This is especially important when all housing market and development options are so constrained, and likely to remain so for the next decade or more.

The next chapter looks at what the estates of ‘corporation suburbia’ are and what they are like. Then follow chapters which home in on specific examples from different parts of the country, on how they are affected by the workings of the housing market, and then – not unconnectedly – on how attitudes to this socially-built stock have evolved. The final chapters try to draw out the potentials, and to suggest what future we might look for in corporation suburbia in the twenty-first century.

Note

1. Commissioned by The Northern Way initiative in 2007–2009 Llewelyn Davies carried out a series of studies which were published by Llewelyn Davies Yeang and Urban Studio; these are cited individually in the bibliography.

![]()

Chapter 2

The Cottage Estates and Their Successors

Corporation Suburbia’s ‘Cottage Estates’

Corporation suburbia is made up largely – but not exclusively – of ‘cottage estates’: large swathes of family houses on their own plots, generally with only a few flats mixed in, though with a marked change in style and feel during the post-war years and into the 1960s and 1970s.

The aim is to show what’s special and valuable about these places. Starting with an attempt to define what England’s corporation suburbia is, and whether it is like social housing anywhere else, the chapter then pokes around at the magic, and loaded, ‘estate’ word, to try and understand what that load is all about.

The rest of the chapter looks at what makes up these estates, and where they came from, leading into three chapters which explore a number of them in more detail.

What, How Much, Where?

The council estates which might be broadly defined as ‘corporation suburbia’ are a sizeable chunk of our total housing stock. We are dealing with about a sixth of all of England’s homes. (Unless otherwise stated, the figures in this chapter relate to England, not the whole UK.)

John Hills’s key report gives the 2003 figures. There were then 21.5 million dwellings of all kinds in England, of which 4.8 million were in ‘predominantly council-built areas’. Of these, 3.25 million were in areas which were ‘mainly houses’ (as opposed to his other two categories of ‘mainly flats’ and ‘houses & flats’). So just over 15 per cent of all homes were in what might be regarded as corporation suburbia. These areas are also a big majority of the country’s social housing: the same figures show that they made up 68 per cent of all the council and housing association stock (Hills, 2007).

Though predominantly council-built, they are not, obviously, all now mainly council-owned. Hills’s 2003 figures record that 50 per cent of the homes in his ‘mainly houses’ council-built category were still in the social sector, but the other half were by then in the private sector. In contrast, the ‘mainly flats’ areas still showed a big majority in social rather than private ownership, in a 73:27 ratio.

Figure 2.1. Familiar all over the country: council-built homes (Upney, in London’s Becontree).

This has of course largely been a Right-To-Buy induced switch. But even after that very strong movement, these ‘mainly houses’ areas still accounted for 40 per cent of all the country’s socially-owned homes. And their location, as expected, is predominantly (69 per cent) described in the Hills report as ‘suburban residential’: that is, not ‘city/ other urban centre’ or ‘rural’.

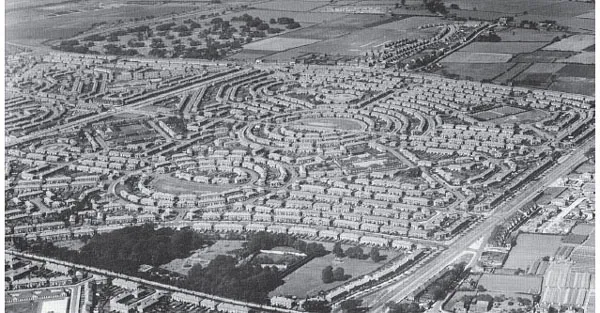

Figure 2.2. Classic inter-war: Norris Green reached out into Liverpool’s green hinterland – with the familiar geometric plan and groupings of these estates. (Source: Liverpool Record Office)

Built When?

As to when corporation suburbia dates from: pre-1945 building accounts for 27 per cent of these estates; 1945–1964 for another 49 per cent; and post-1964 for 22 per cent (Hills, 2007). The classic inter-war cottage estates are thus less than a third of the total in the council-built suburbs.

Their post-war (that is, post-1945) successors are generally recognizable by their more stripped-down exteriors. Later on, the layouts changed too, with the 1950s/1960s shift to designs such as ‘Radburn’ planning which sought to separate cars and pedestrians. Altogether, the post-war building actually accounts for much more in total than the pre-1939 construction.

Figure 2.3. The 1960s Radburn ideal: carefree play in car-free walkway streets. (Source: Town & Country Planning Association)

Part of Suburban Life

In their various forms, then, these suburbs are a big and characteristic part of the English housing scene. Along with their privately-built neighbours, they dramatically changed the shape of urban Britain in the 20 years after the end of the First World War: ‘The residential growth of towns and cities in interwar England was practically synonymous with the creation of garden suburbs’ (Whitehand and Carr, 1999). The municipal building effort also forms a very significant proportion of all our suburbs. Definitions are difficult: but as one careful study of twentieth-century suburbs points out, the timing and scale of suburbia varies a lot between places, notably in the case of London whose suburbs grew faster and earlier than anywhere else between the wars (Whitehand and Carr, 2001). But a look at a medium-sized middle-England sort of a place like Leicester can perhaps give a feel for the sort of scale of presence that th...