![]()

A

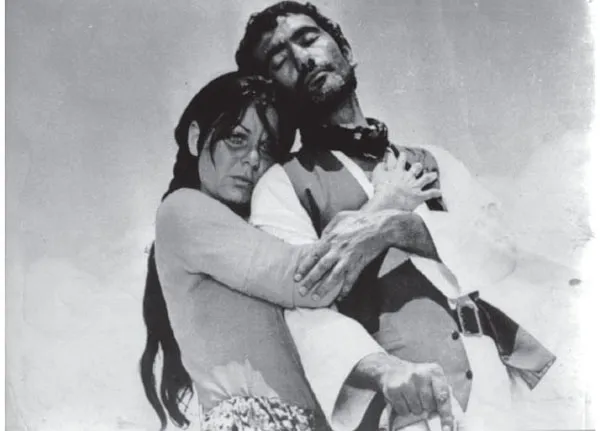

Acı / Pain (1971) is the second part of the trilogy that began with Ağıt / Elegy, and was completed with Umutsuzlar / The Hopeless Ones, the same year. A milestone of Turkish cinema, the film shows a unity of style with its steady tempo and constant tension in the story of Anatolian men pushed to crime by customs and traditions. Ali (Yılmaz Güney) returns to his village after serving 15 years for killing Yasin. Visiting Yasin’s grave, he asks forgiveness, offering himself to the bereaved family as a surrogate son. Rejected at first and attacked with a spade by Yasin’s sister Zelha (Fatma Girik), he is accepted into the family gradually and romance is on the way, but evil forces of society will not leave him in peace. Blinded by Haceli Agha’s (Hayati Hamzaoğlu) men, who kill Yasin’s father, Ali has no choice but to respond to violence with violence. An excellent marksman in his youth, he concocts an ingenious device for target practice using bells that Zelha places in different posts and manipulates with ropes. When the enemy arrives, Zelha rolls the bells in the direction of the attacker and Ali hits.

Figure 1 Yılmaz Güney and Fatma Girik in Acı / Pain (Yılmaz Güney, 1971) (Courtesy of International Istanbul Film Festival)

Figure 2 Acı / Pain (Yılmaz Güney, 1971) (Courtesy of International Istanbul Film Festival)

Made during the political turmoil and the economic crisis, the film demonstrates Güney’s remarkable circumlocution skill to avert the scrutiny of censorship while sending his message – be resourceful to combat oppression – to the audience, the bells serving as a pertinent trope for resistance. The samurai–spaghetti-western genres are revisited through the desolate landscape of Cappadocia; the character of Güney like a quiet and aloof Clint Eastwood (A Fistful of Dollars, Sergio Leone, 1964) and a samurai in white tunic and loose pants; the loyalty/disloyalty issue (the prison mate coveting his woman and denouncing him); the blood feud; the revenge; the romance; the fighting prowess; the relation of the hero to law / lawlessness; the violence; the decline of a traditional way of life and the demise of all principal characters in the finale. The gunplay that follows the confrontation between the lone gunman and the rogues is a fantastical sequence choreographed with precision. Relying on the gaze, the trademark of Güney, the dialogue is sparse, reinforcing the feeling of oppression and entrapment. The mise en scène contrasts the verticality of the ‘fairy chimney’ rock formations that shelter but also entrap and the horizontality of the sweeping landscape that promises freedom but not refuge. Haceli Agha, the emblem of masculinity defined by power and control is juxtaposed with Ali, the feminine element – the humble man seeking peace and expressing his feelings with flowers. Güney reiterates in the film the futility of individual salvation. Ali has transformed himself but the society has remained the same and violence is fatal for everyone.

Director, Screenwriter: Yılmaz Güney; Producer: Nami Dilbaz and Üveyiş Molu; Production: Başak Film and Özleyiş Film; Cinematographer: Gani Turanlı; Editor: Şerif Gören; Music: Metin Bükey; Cast: Yılmaz Güney, Fatma Girik, Hayati Hamzaoğlu, Mehmet Büyükgüngör, Oktay Yavuz

Acı Hayat / Bitter Life (1962), a ‘black passion’ film that is considered within the social realist movement focuses on housing shortages in the metropolis for the less advantaged, a staple theme in the cinema of a country that has experienced rapid industrialization and massive internal migration. Manicurist Nermin (Türkan Şoray) and welder Mehmet (Ayhan Işık) are in love, but lack the resources to establish a family. The hopes of the poor are built on lottery tickets, or a prosperous spouse, ambitions that often culminate in disappointment, or tragedy. As the city transforms itself, construction of concrete apartment blocks menace the poor neighbourhoods, the desolate modern landscape of new slums with the straight lines of the recent constructions, dead in their modernity evoking Italian neo-realist films, particularly Antonioni and Fellini. The rich are corrupt, their morals fluid, their women superfluous parasites in gauche costumes who kill time playing cards or having a pedicure while their irresponsible offspring party. Encouraged by her mother, Nermin, after a drinking binge, concedes to the advances of Ender (Ekrem Bora), the spoilt son of a prominent speculator, and Mehmet, who is now rich and merciless, sleeps with Ender’s sister Filiz (Nebahat Çehre) for revenge, although open-minded Filiz gives herself willingly.

Both Nermin and Mehmet are the adventurer / parvenu (Bakhtin 1981: 125–6). As a manicurist, she eavesdrops on the intimate secrets of the rich but has no place among them; she remains lowly until the end. Mehmet is the real parvenu, the nouveau riche without social pedigree, the ‘Great Gatsby’ who finally arrives, but still cannot partake.

The living spaces establish the binaries of the rich and the poor according to Yeşilçam clichés; the poor in traditional wooden houses without water or electricity, but in neighbourhood atmosphere, the rich isolated in imposing villas in affluent suburbs. Nermin is seduced in an upscale holiday resort, deserted and uncanny, where Mehmet builds a modern villa, but admits that a house needs soul: ‘Damn these cement graves!’ Traditional Turkish music accompanies the images of the poor dwellings and Latin and North American popular music of the period, the extravagant mansions. Tight camera angles as Nermin and Mehmet dash down the decrepit staircase of an apartment they visit; the vertical tracking shot of two elevators – Nermin descending with her honour lost and Mehmet ascending as a social climber – and finally, the angle–reverse-angle shots of Nermin and Mehmet in the denouement confronting each other under the concealed gaze of Filiz are signature moments of Erksan’s work that also benefits from the black and white contrast. Erksan’s narrative nonetheless remains Eastern, embedded in local customs and androcentric religious traditions despite its modern film language and the frequent use of jazz music (Ornette Coleman). Women are peons, their ‘honour’ to be exploited at will, for passion or for revenge. Mehmet punishes Nermin for her greed by trashing her while she begs forgiveness. The fate of the woman who deviates is death: to cleanse her sin, Nermin walks to the sea on the beach where she was seduced.

Considered as one of the best love films ever made, Bitter Life was very successful commercially. The romance element was an inspiration to several other films, in addition to two television series that were made in the 2000s on the same subject. With Bitter Life Türkan Şoray received her first award during the first Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival.

Director, Screenwriter: Metin Erksan; Producer: Muzaffer Arslan; Production: Sine Film; Cinematographer: Ali Uğur; Editor: Özdemir Arıtan; Art Director: Semih Sezerli; Music: Fecri Ebcioğlu; Sound: Tuncer Aydınoğlu; Cast: Türkan Şoray, Ayhan Işık, Ekrem Bora, Nebahat Çehre

Açlık / Hunger (1974), a staunch indictment of the feudal system that oppresses men and women opens with the cries of babies and the image of a pregnant woman with six hungry children. Still a child, Meryem was sold to the landlord (Hüseyin Kutman) as a domestic servant and she has been sexually exploited. Hasan (Mehmet Keskinoğlu), unable to find a woman to share his poverty, marries the ‘soiled’ Meryem (Türkan Şoray), but leaves for the city when the draught destroys hopes. To feed her starving children, Meryem threatens the landlord with a knife demanding food in exchange for her once lost virginity. In a traumatic finale, Meryem is lynched by the desperate crowd for a piece of bread while the rain finally starts to pour.

Displaying filmic allegories of underdevelopment, Hunger is a precursor of Bilge Olgaç’s socio-politically oriented and gender-based films by exposing the retrograde customs of merchandizing little girls and childbearing unaided by pulling a rope. The use of a dissolve overlapping the image of the little girl washing the floor observed by the landlord, with her grown-up image is a well-designed transition, which skilfully avoids objectifying her body. The implication of the off-screen rape through the gaze of the village fool, who finds her half-naked on the cotton pile, is another example of Olgaç’s deliberate avoidance of voyeurism. Considered by doyen film critic Atilla Dorsay as the best film of Olgaç until its date (Dorsay 1989: 100), the weak point of Hunger is the one-dimensional presentation of the male characters: landless peasant Hasan is gentle and loving, whereas the landlord is immoral and despicable (a Yeşilçam cliché regardless of the political orientation).

Director, Screenwriter: Bilge Olgaç; Producer: Fethi Oğuz; Production: Funda Film; Cinematographer: Ali Uğur; Editor: İsmail Kalkan and Özdemir Arıtan; Music: Yalçın Tura; Sound: Necip Sarıcıoğlu and Mevlut Koçak; Cast: Türkan Şoray, Hüseyin Kutman, Mehmet Keskinoğlu

Figure 3 Cahide Sonku as Aysel in Aysel, Bataklı Damın Kızı / The Girl From the Marshes aka Aysel, the Girl From the Swampy Roof (Muhsin Ertuğrul, 1935) (Courtesy of International Istanbul Film Festival)

Adaptation of literary and theatrical works and popular forms like comic books has been prevalent throughout Turkish film history starting with the early years. Himmet Ağa’nın İzdivacı / Marriage of Himmet Agha (Fuat Uzkınay and Sigmund Weinberg, 1916–1918) from Molière’s play, Le Mariage Forcé / Forced Marriage (1664); Aysel, Bataklı Damın Kızı / The Girl From the Marshes aka Aysel, the Girl From the Swampy Roof (Muhsin Ertuğrul, 1935) from Selma Lagerlöf’s novella, Tösen från Stormyrtorpet (1908); Şehvet Kurbanı / The Victim of Lust (1939) from Joseph von Sternberg’s film, Der Blauer Engel / The Blue Angel are some of the noteworthy examples. In the absence of legal procedures regarding copyright, Yeşilçam produced innumerable remakes of Hollywood, European and national films, ‘borrowing’ from filmic and non-filmic sources without acknowledging credit. According to veteran historian Giovanni Scognamillo, the main reasons for the adaptations and re-makes were: the number of productions exceeding the capacity of the film-workers – screenwriters were in demand particularly in the 1960s, when the annual production reached 200s; the inadequate production conditions and the possibility of commercial success by reaching wider audiences through popular works. Some of the foreign adaptations were loyal to the original, whereas others were Turkish versions, with alterations in characters, time and space, or adaptations to local lifestyles. The faithful adaptations of Cinderella or Don Quixote, or the authentic recreation of American or Italian superheroes, or cartoon characters were short lived and did not enrich Turkish cinema. The Turkish versions done in haste were not successful either, mainly because of the discrepancy between the narrative and the actual location (Scognamillo 1973a: 61–73). Ertem Eğilmez’s Sürtük / The Tramp (1965) (and its 1970 re-make) from Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (1913), a remake of Charles Vidor’s Love Me or Leave Me (1955); Metin Erksan...