![]()

III

READINGS

3 An archetypal landscape of the mind (Fata Morgana)

![]()

3

On seeing a mirage

Amos Vogel

1970

Basic philosophical issues in cinema were brought home with a vengeance on a recent revisit to Werner Herzog’s Fata Morgana. Herzog is one of the masters of the modern cinema, and Fata Morgana is one of his key films. In its shimmering opacity it occupies a unique place in the director’s oeuvre, quite separate from his deceptively “realistic,” plotted films (Aguirre,Signs of Life, Woyzeck,Kaspar Häuser, Stroszek, et al.). Fata Morgana is the paradigm of Herzog’s more overtly experimental films (such as Even Dwarfs Started Small, Precautions Against Fanatics, Last Words, The Unparalleled Defense of Fortress Deutschkreutz). It provides a key to the director’s universe, and could only have emerged from a country ravaged by two world wars, total fascism, the traumas of scientific genocide and saturation bombings.

Fata Morgana is a sardonic, melancholic comment on mankind’s shaky position in the universe. Its elusive, hallucinatory images (accompanied by sacred sixteenth-century Guatemalan creation myths and Herzog’s avant-garde texts) coalesce into devastating dream tableaux that cunningly exploit trappings of conventional reality.

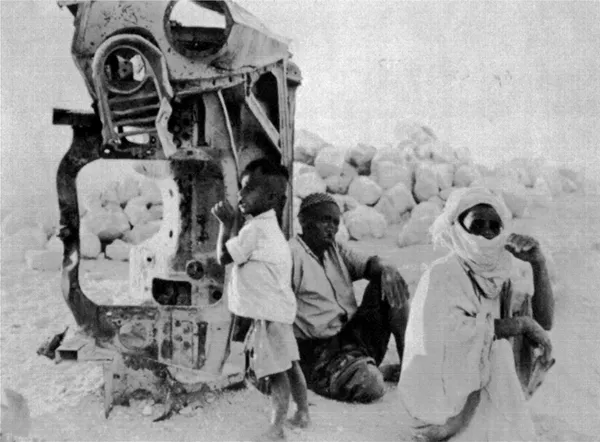

The land, though Africa, is an archetypical landscape of the mind. The inhuman grandeur of primeval dunescapes and horizons reveals man’s triumphant and empty rape of nature. Factories (their initial purpose unfathomable) abandoned in the desert; decomposing vehicles, military supplies, rotting symbiotically with animal cadavers in intimate, frozen embraces that melt into the soil before our eyes; emaciated black children; flies and insufferable sun.

“In Paradise,” says the narrator, “man is born dead” - a typical Herzog line. Herzog, privately, refers to Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights’, his paradise, too, “contained God’s fatal errors from the start … visible only in corners, so that the painter would not be branded a heretic.“ The result is an obsessive, hypnotic, iconoclastic interior travelogue that attempts to project chaos and irrationality in a direct, unmediated form. (”Chaos is in all of my works … it has positive aspects.”)

Among the filmmaker’s ideological weapons are absurd, bizarre, goal-directed tableaux that address themselves to the unconscious. A determined young German teacher stands knee-deep in water with her black flock, senselessly forcing them to repeat the phrase “Blitzkrieg is madness” in German. A ridiculous, yet threatening frogman, equipped with grotesque fins and snorkels, desperately holds on to a huge turtle and breathlessly informs us that it has flippers to move, a mouth to take nourishment, and “a behind where it all comes out again.” A sweating, fascist German lizard-lover, in a hopeless desert, (obviously affected by years in the African sun) – his square-jawed German visage distorted by madness and black glasses – sadistically manipulates a lizard, comments on its habits, and continuously attempts to avoid getting bitten by it, while flies hover over festering wounds on his hands.

The strongest sequence may be a catastrophic metaphor of hell on earth: a catatonic drummer and a tacky female pianist on a tiny stage in a brothel perform a piece they have played a thousand times without any emotion, endlessly, off-key. “In the Golden Age, man and wife live in harmony,” the commentator says, as they are photographed head-on, with all the merciful cruelty of a humanist filmmaker who must show everything. At the end of the piece, they remain immobile. There is no applause.

Fata Morgana emerges as a sardonic comment on technology, sentimentality, despoliation of land and people, projected by a suffering visionary tremblingly aware of our limited possibilities, outrageous perseverance, and almost bearable ridiculousness.

It was with this film that Herzog progressed from the promise of genius implicit in his earlier films to a level of artistry at once more subversive and more inaccessible; for here, working solely with the materials of reality, Herzog, in a cosmic pun on cinéma vérité, recovered the metaphysical beneath the visible. It is only in such works that we achieve intimations of the radical humanism of the future.

1980

Not having seen the film for ten years, I was more than eager to expose myself again to the acidity and black humor of this monument of icy subversion. The outcome was disaster.

Not that the indispensable, courageous repertory theater was empty. It was packed, for by 1980 (with the customary decade or two of delay) Herzog had finally become a cult figure. Viewers just born when he had started in films waited expectantly for further revelations in the Herzog canon.

Here is what they and I experienced. Having originally been exposed to the crystal clarity and sharp-edged photography of a first-generation 35mm print projected on a large screen, I found myself peering uncertainly into the dim, contrastless recesses of a cheap 16mm print, decorated with striations and scratches. The tones – the gross and subtle details so central to the film – were gone, reconfirming that its magical power derived from a profusion of dream images that are subliminally responsible for those profound psychic shocks inevitably associated with all great moments of visual cinema. There were protagonists of central tableaux suddenly “missing” because of lack of contrast; there were black areas that had turned gray, and white areas that had turned gray as well. There had been those unforgettable, shimmering reflections of heat waves connected with an important object in the far background, shuttling back and forth impotently, obsessively, in several separate sequences – a symbol considered basic to the film by Herzog; this was missing. There were the identical shots, obsessively repeated, of a huge jetliner (technology itself) touching down at least seven times in “primitive” Africa amidst hallucinatory blazes of polluted grandeur; a threat; a monster; its impact was now entirely obliterated by lack of detail. There was the abandoned factory, its blood-red steel girders squatting threateningly against a black, incongruous, pre-industrial background, a bloodstain upon nature; its colors were now washed out of existence.

Simultaneously, within the theater, one stared, unbelievingly, into brightly lit, red exit signs, situated in front of the viewer, an incessant anti-illusionist onslaught on the entire film. The projectionist – perhaps underpaid and undertrained, “doing a job,” not particularly concerned with Herzog’s philosophical musings nor helped by the murkiness of most of the images – tantalizingly projected the entire work just sufficiently out of focus to make the viewer unable to feel the magic and power of the sharply defined graphic compositions. The audience, non-comprehending for all the obvious reasons, had grown restless, moving about in their squeaking seats, embarking on equally squeaky trips across ancient wood floors to bathroom or exit or lobby conversations, dimly overheard inside the theater, as were the projectionist’s muttered imprecations and the rattling of an under-serviced 16mm projector. The tired screen was overlaid with the grayness of generations of films; it was also pathetically small in respect to the size and shape of the theater, creating the infamous postage-stamp effect which reduced this subtle visual work to a series of dim messages from afar – imperfectly grasped, spectral projections of Kafkaesque situations with just enough visibility of possibly portentous but inexplicable events to create disorientation.

In an act of supreme irony, Herzog’s lament for the unfulfilled promise of a Genesis and a Paradise that somehow failed had been turned against him. Fata Morgana refers to a magnificent, false mirage for desperate travelers; the condition of print and exhibition subverted the film itself into what it successfully deplored: the failure of a planned piece of perfection.

It is, of course, entirely questionable whether customary modes of commercial exhibition are suitable for meditative, non-narrative works closer to Robert Wilson or Richard Foreman than to John Ford. Perhaps Fata Morgana needs to be seen, in 35mm only, from third row center, on a large screen, one to ten spectators at a time, none in adjoining seats. Perhaps such works demand detailed program notes, to explicate background and context. Or must the magnificent powers of human imagination forever be yoked to the requirements of commerce?

What kind of art is this that depends so heavily on the nature of its presentation, and to which access in a form close to its “original” becomes ever more impossible? What shall we do with the evanescence of film stock (technologically and economically based), with cheap laboratories (inevitable in a profit-oriented society), with businessmen “understandably” skimping on making appropriately timed prints of meritorious works that have proven unprofitable? What shall we do with equally praiseworthy exhibitors only able to operate in ancient theaters, with tired projection systems, again, and inevitably, responding to profit-loss considerations? What shall we do with visual cinema if we cannot see the visuals? What kind of art is this, in which an exhibitor, laboratory worker, distributor, and projectionist have the power to determine the nature of one’s experience of a work, acting as unwelcome mediators between viewer and artist?

It is as if King Lear were available only one day per decade in one city per continent, in fiftieth-generation, pirated, Hong Kong copies of which entire pages were missing, individual paragraphs not quite readable, portions of characters obliterated with frustrating intimations of potential greatness; the stuff of Borges, of Kafka, of Marquez.

What, then, is this film Fata Morgana? Where is “the text” to be deconstructed? Is it the original stored in a vault for no one to see? Or am I to report my “knowledge” of the closest approximation to it – a 35mm print – to readers and students, as if I were Marco Polo, bringing back (ten years after) my “impressions” of certain stupefying riches of the east fleetingly glimpsed but once?

To be resigned to what is being broached here (and therefore to the fate of Fata Morgana) is in consonance with Herzog’s somber world view; he is explicit about this. Great works will arise in every generation (less often since the conglomerates have taken over); they live for a moment of historical time, then slowly fall back into the undifferentiated flux – itself a symbol of recurring birth, maturity, and death. They are flashes of brilliance that temporarily “light our ways” along the corridors of darkness until extinguished by the great Indifferent Projectionist in his crochety booth, muttering obscenities to himself as he brings the uncertain discourse to an end amidst squeaks, misunderstandings, and obtrusive exit signs.

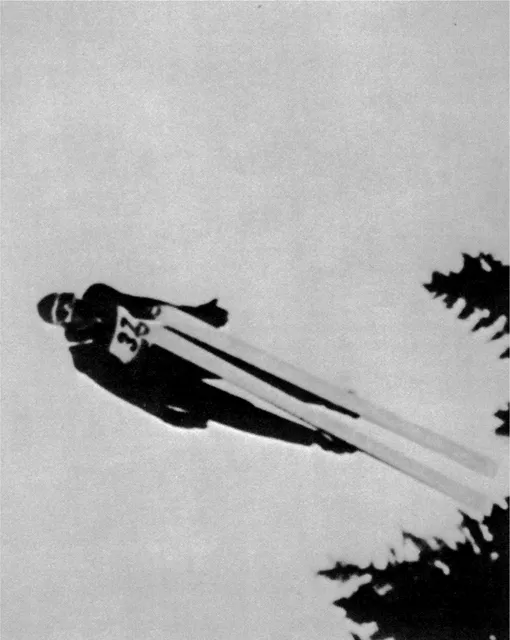

And yet, in every audience, there is one young person, as if struck down by what he sees, who ultimately will once again perform the eternal dance of divine madness: the creation of masterpieces. Briefly carried in triumph on the shoulders of believers, he, too, is ultimately slain by mortality and indifference.

![]()

4

Last words: observations on a new language

William Van Wert

At first glance eclectic, obsessive and renegade, the documentaries of Werner Herzog do, finally and inevitably, fit into the elaborate intertex-tual fabric of his fiction films. Even as Herzog was gaining notoriety outside of Germany for feature films like Signs of Life, Even Dwarfs Started Small and Aguirre, the Wrath of God, he was simultaneously submitting short films to major film festivals like Oberhausen. These documentaries are not considered “lesser” works by Herzog himself, and, in fact, they are crucial to understanding the creative trajectory of this most important of the filmmakers to have emerged from the so-called New German Cinema.

Many other internationally known filmmakers, Herzog’s contemporaries, began their careers in the documentary form, then moved into feature-length fiction films, only to abandon documentaries, by and large, after commercial success: Jean-Luc Godard, Nagisa Oshima, Sembene Ousmane, for example. For these filmmakers, the documentary film seems to have been an apprenticeship, dictated more by financial constraint than by personal preference. Why, then, has Herzog persisted in making documentary films, especially when they are time-consuming and questionable in terms of reputation, distribution, and financial rewards? The reasons are many and provocative.

One of the reasons for Herzog’s persistence in the documentary form has to do with distribution. Whereas his documentaries, by subject matter and running time, are excluded from traditional film-booking circuits, they are appropriately suitable for film festivals, where German shorts got their first breakthrough in the international market, and for television, an industry much stronger in Germany than the film industry because it is government-subsidized. While Herzog may promote the myth that he has been obscured in his own country, he quietly continues to make documentaries whose running times fit the requirements of German national television programming.

Another reason has to do with influence. It is perhaps fashionable, as a question of national cinema, to see Werner Herzog as a neo-expressionist, especially since the making of Nosferatu and Woyzeck,to find links between his themes and those of Wiene, early Mumau and Lang, and even to trace a film like Fata Morgana back to Todd Browning’s Freaks. But the documentary Herzog, both in composition and in irony, derives from the French surrealist tradition, from the biting Land Without Bread of Luis Bunuel to the documentaries of Chris Marker.1 The romantic sensationalism to which Herzog is sometimes prone in his approach to his fictional subjects is curbed in the documentaries by the same cerebral wit and sudden irony that informs the French surrealist shorts. As for them, so too for Herzog, the documentary is not strictly referential or simply derivative of reality, but a simultaneous exploration of subjects’ lives and cinematic forms.

Other reasons for Herzog’s documentaries, however, can be found in the particular temperament of Herzog himself. First, the experimenter in Herzog can best be satisfied in the documentaries. The very same inclinations that have gotten him into trouble in the fiction films (hypnotizing actors in Heart of Glass; the repeated use of former asylum inmate Bruno S. in Kaspar Hauser and Stroszek; the strained manipulation of native Indians in Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo) are much less problematic in the documentary form, where the question of manipulation is more subtle, more obscured, because Herzog himself often “acts” in these films as interviewer, filmmaker or engagé spectator. He “manipulates” himself, then, in terms of compositional positioning, inserts and point of view, while his found subjects are ostensibly encouraged to play themselves, not some preordained role.

Thus, there is no need to confront the labor practices of the feature films in his documentaries. There is, instead, a valorization of the documentaries in the fact that Herzog “controls” them better than the fiction films, from concept to post-production and distribution. Shy, estranged, reclusive and idiosyncratic behind the camera, Herzog emerges as something of an exhibitionist, even a narcissist, in front of the documentary lens. At the same time, with the smaller crews required for the documentaries, he can maintain, and often enhance, the intimate bond he has with Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein, Thomas Mauch and Ed Lachman, his cinematographers; with Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus, his editor; and with musical co...