- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 1991. This work is a follow-up on the European Science Foundation Project (ESF) entitled the Ecology of Adult Language Acquisition. The subject of this study is the process of untutored language acquisition in adults and the focus is on Turkish and Moroccan immigrants during the first three years of their stay in the Netherlands.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

This chapter introduces the area of investigation of the present study on adult untutored language acquisition: talking about people. First, the referential domain and the encoding devices are discussed briefly. Next, the general aims and research questions are specified. Finally, a European Science Foundation research project is introduced. This ESF project provided the data base and framework for the present study.

1.1 TALKING ABOUT PEOPLE

The subject of this study is the process of untutored language acquisition in adults and the focus is on Turkish and Moroccan immigrants during the first three years of their stay in the Netherlands. In this period they started to learn Dutch as a second language without any formal tuition.

The perspective on language acquisition taken in this study can be characterized as an approach which (1) starts from a concept-oriented referential domain, and which (2) focusses on the systematics of encoding devices (i.e. the form-function relationships) in learner varieties of a target language.

1.1.1 REFERENTIAL DOMAIN

A concept-oriented approach starts from a language-independent semantic and cog-nitive domain (cf. Von Stutterheim & Klein 1987). All successful verbal communication requires reference to the domains of people, space, and time. Basic types of person and spatiotemporal reference are studied from cross-linguistic, psychological and developmental points of view (see for example Rauh 1983, Jarvella & Klein 1982, Lyons 1977, and Miller & Johnson-Laird 1976).

The conceptual domain this study deals with is “people”. Talking about people involves “the act of referring”. Although intuitively it is fairly obvious which referential domain corresponds to the label “people”, a precise definition is complex. According to Lyons (1977:436–452), people, together with animals and things, are so-called first order entities. In contrast to second and third order entities, first order entities can be said to “exist”. Second order entities “occur” and they include events, processes and states-of-affairs such as “the sunset”. Third order entities are abstract propositions such as “love” and “peace”. First order entities are relatively constant to their perceptual properties, are located in a three-dimensional space and they are publicly observable. In short: something is a first order entity if it “exists and can be referred to” (Lyons 1977:445). The domain of people is a subset of first order entities and restricted to human beings.

Successful reference to people means that “the referent is sorted out of a set of possible alternative referents” (Perdue 1984:139). The communicative role which a referent fulfils is important. There is a fundamental difference between “first person reference” (i.e. reference to the speaker), “second person reference” (i.e. reference to the addressee), and “third person reference” (i.e. reference to the person who is neither the speaker nor the addressee). In particular the origin of these traditional terms is illuminating. The classical grammarians conceived of a language event as a drama in which only the speaker and the addressee are actually participating: the principal role is played by the first person, the subsidiary role by the second person; third persons are negatively defined in that they do not correlate with any positive participant role (cf. Lyons 1977:638). Following this distinction we will talk about first role person reference (henceforth: 1st role reference), second role person reference (henceforth: 2nd role reference), and third role person reference (henceforth: 3rd role reference).

1.1.2 ENCODING DEVICES

Every language has numerous devices for the encoding of person reference. Between languages there are remarkable similarities and differences in the construction and differentiation of the set of possible referring expressions. In many languages the encoding of reference to people is done through nouns and pronouns. Nominal reference involves a set of proper names and more or less complex nominal groups (e.g. Ahmet, my brother, my neighbour's sister); pronominal reference is based on an exhaustive list of frequently used and predominantly monosyllabic word forms (e.g. I, you, he, etc.).

The historical development of languages suggests that the functional distinction between pronominal and nominal reference is not absolutely clear-cut (cf. Lyons 1977:179). Nevertheless, in most languages each of them corresponds with a distinctive way of successfully sorting out a referent from a set of possible alternative referents. Globally speaking, pronominal devices constitute the unmarked encoding of person reference, whereas nominal devices constitute the marked encoding. This certainly holds for the encoding of 1st and 2nd role reference. For these two types of reference the encoding through pronouns is usually adequate, because from the situational context it is clear who are the speaker(s) and addressee(s). Also for 3rd role reference, although to a lesser degree, pronominal devices constitute the unmarked encoding. Referents have to be established nominally in the discourse, but for maintenance of reference encoding through pronouns is adequate (e.g. Ahmet goes to his sister in Turkey. He hasn't seen her for two years).

1.2 AIM AND SCOPE

Adult learners of a second language (henceforth: L2) will be familiar with a set of concepts through their first language (henceforth: LI), but they will not be familiar with the specific ways in which a comparable set of L2 concepts is organized and encoded through linguistic devices of the L2. With respect to the conceptual domain of temporality, recent studies on LI and L2 acquisition provide empirical support for the importance of Slobin's claim of “Thinking for speaking” (see Slobin 1987 and Bhardwaj et al. 1988 for further references). The language which we learn as a child is not a neutral coding system of an objective reality. Each language is a subjective orientation to the world of human experience, and this orientation affects the ways in which we think while we are speaking (Slobin 1990). Communication in a specific language implies a specific ordering of cognitive concepts. The language acquired during childhood has firmly entrenched itself and will affect the acquisition of other languages at a later age.

Especially during the early stages of language acquisition, learner varieties necessarily consist of a restricted set of linguistic devices which learners have to use as efficiently as possible in daily interactions with native speakers of the target language. The questions relevant to this study are: how do adult language learners start out encoding person reference, how does their repertoire develop, and why do they make the choices they make?

The assumption is that the variety of the target language used by the learner is a dynamic and unique system that partly coincides with and partly differs from the target language. Learner varieties are systematic not only in their internal organization, but also in the order of various stages that can be distinguished. The systematics of learner varieties are reflected in form-function relationships.

Central aims of the present study are the description and explanation of the learner's preferences in the encoding of talking about people. The basic research questions can be specified as follows:

I. Which linguistic encoding devices are used for talking about people in L2-Dutch varieties of Turkish and Moroccan adults?

II. Which developmental patterns can be found in subsequent stages of language acquisition?

III. How can learner preferences be explained?

The present study is a follow-up on the European Science Foundation project en-titled the Ecology of Adult Language Acquisition (Perdue 1984). This ESF project provided the framework for the present study. The area of investigation, person reference, derived from the theoretical perspective taken in the ESF project and the focus is on those Turkish and Moroccan adults who played a central role in that project as second language learners of Dutch.

1.3 THE ESF PROJECT

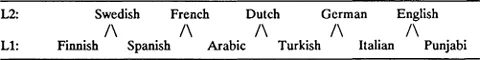

From 1982 to 1987 an international research project was initiated under the auspices of the European Science Foundation (ESF) in Strasbourg. This project was carried out simultaneously in Great Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, France and Sweden. It focussed on processes of spontaneous (untutored) second language acquisition in adult immigrants in Western Europe. The ESF project is different from most previous studies in that it has both cross-linguistic and longitudinal dimensions. With respect to the cross-linguistic dimension the relatively young tradition of second language research has so far had a rather strong Anglo-Saxon bias. It is an American diet in which English is most commonly the source or the target language (cf. Ellis 1985:74). In the ESF project, however, five target languages (L2) and six source languages (LI) were combined in the following way:

The selection of these source and target languages was based on two criteria (see Perdue 1984:29–31). First, the chosen source languages belong to the major immigrant languages in the five Western European countries under consideration. Secondly, it should be possible to make a linguistically interesting comparison as four of the five target languages are Germanic, and three of the six source languages are non-Indo-European. With respect to the longitudinal dimension of the ESF project Klein & Perdue (1988:5) pointed out that research on second language acquisition by adults almost exclusively has a cross-sectional design. Conclusions about the process of language acquisition are mostly based on a comparison of different language learners at different stages of L2 acquisition. Longitudinal studies that focus on the L2 acquisition process of the same learners over a longer period of time are scarce (exceptions being Schumann 1978a, and Huebner 1983 for instance). The longitudinal design of the ESF project was as follows: over a period of two-and-a-half years each month audio/video recordings were made of four adult language learners (informants) for each source-target language pair (Total = 10×4 = 40 informants). Each informant took part in a variety of language activities. The data collection resulted in an extensive and varied computer-stored corpus of language data. A detailed description of the design and aims of the ESF project was given in Perdue (1984).

The ESF project focussed on the “analysis” and “synthesis” tasks language learners are confronted with (cf. Klein 1986:63–109). The analysis task consists of segmenting the available input into meaningful units and bringing the resulting information in line with the situational context of the utterance. This task was dealt with in two studies included in the ESF project: Ways of Achieving Understanding (Bremer et al. 1988) and Feedback in Adult Language Acquisition (Allwood 1988). The synthesis task consists of turning meaningful units (sounds, words, etc.) they have learned into understandable speech. Specific studies were made of the learner's problem of arranging words to form larger units of speech: Utterance Structure (Klein & Perdue 1988), and of locating the objects or events they talk about: Spatial Reference (Becker et al. 1988) and Temporal Reference (Bhardwaj et al. 1988).

In the ESF project substantial analyses were carried out for the conceptual domains of space and time. However, person reference was only touched on to a limited extent: at the word level pilot studies were carried out on the acquisition of pronouns (Broeder, Extra & Van Hout 1986 and Broeder et al. 1988:86–113), and at the discourse level some analyses were carried out for the establishment and maintenance of person reference in narrative discourse (Klein & Perdue 1988).

1.4 OUTLINE OF THE PRESENT STUDY

Any study on language acquisition must be selective in the number and type of informants and in the amount and variety of data to be collected. First of all, a choice has to be made between a longitudinal and a cross-sectional research design. In the former, the language behaviour of one and the same informant or group of informants is observed for a certain period at specific intervals. In the latter, one sample of language behaviour of a specific group of informants is compared simultaneously with other samples of other groups (at a less or more advanced level of language proficiency for instance). In contrast to cross-sectional studies, where the time factor has actually been eliminated, longitudinal studies can give a real picture of language development over time. Within both types of research design it is possible to make statements about sequences. A cross-sectional design will allow statements on the order of accuracy (or difficulty) of a given series of expressive devices, whereas only a longitudinal design will allow statements on the order of acquisition. In many cross-sectional studies it has been tacitly assumed that an observed order of accuracy reflects a non-observed order of acquisition. In other words, synchronic data have been interpreted diachronically. It should, however, be borne in mind that such an interpretation is based on assumptions, the validity of which will have to be tested empirically. The dominance of cross-sectional over longitudinal studies on language acquisition derives from the fact that longitudinal research is by definition time-consuming (and therefore often expensive), and cannot easily be applied to large numbers of informants.

Given the primary interest of in-depth, micro-analytical insights into processes of language development over time, this longitudinal study will be based on a large amount and variety of data, and on a limited number of informants rather than the reverse. The same informants will be followed over time from the first stages of their L2 acquisition over a period of almost two-and-a-half years at intervals of approximately one month. The outcome of this study could serve as a basis for further research involving larger and more representative samples of informants.

This study focusses on those four informants who played a central role in the ESF project as L2 learners of Dutch: the Turks Mahmut and Ergun, and the Moroccans Mohamed and Fatima. For these core informants all interactional data that were collected will be analysed. Cross-learner and cross-linguistic comparisons are made through analyses of L2-Dutch of two Turkish adults (Abdullah and Osman) and two Moroccan adults (Hassan and Husseyn). These shadow informants also participated in the ESF proj...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- European Studies on Multilingualism

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Table of Contents

- Notation conventions

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Study of Language Acquisition

- 3 Informants and Data Base

- 4 Cross-Linguistic Perspective on Pronouns

- 5 First and Second Role Pronominal Reference

- 6 Third Role Pronominal Reference

- 7 Referential Movement

- 8 Reference to Possession

- 9 Conclusions and Outlook

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Talking About People by Peter Broeder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.