![]()

| Bachelard: | I have been told that there are a number of rebel leaders who have been in government before, who belong to the president’s clan, and who have chosen today to be in rebellion. Is this true, and if yes, how do you explain this? |

| Lol Mahamat Choua: | It is very true … Take the example of General Nouri, who is my neighbor. Here is his house, just on this side, five meters away. He was a minister, at various times, in Déby’s government. His other colleague, the main one, Abakar Tollimi, was general manager of the Chadian school of public administration. He is a young and valuable executive. His house is just next to mine…This is why they came to arrest me on 3 February around midnight, on my doorstep. I was accused of holding a secret meeting with Nouri and the others…For example, Soubiane Hassaballah was Déby’s first interior minister when he took power in 1990. And I only cite these individuals because I know them very well. Many rebels today have either been a minister, or a general manager or something like that. Most of the leaders I know personally were closely collaborating with Déby at one point or another. |

(My translation, interview with Mr Lol Mahamat Choua, former President of the Chadian Republic, National President of the RDP Opposition Party, N’Djamena, June 2008)

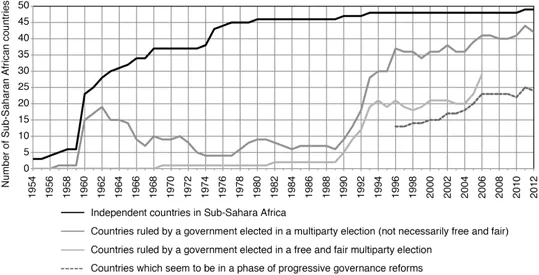

Sub-Saharan is Africa currently experiencing a wave of governance reforms,1 in the same way as it experienced a wave of independence from 1956 to 1968,2 and a wave of democratization after 1989.3 These three successive waves belong to the same logic. The African people’s fight for decolonization and democratization aimed at a final goal that cannot be achieved without a fight for good governance — the goal of being ruled by governments which they have elected and can hold accountable. Focusing on four case studies, this book not only argues that a wave of governance reform is currently taking place. More importantly, it examines the conditions under which a country will move forward on the governance reform agenda, stagnate, or step backwards.

Figure 1.1 Independence, democratization and governance reform in the 49 countries of Sub-Saharan Africa

Signs of positive change are perceivable in many countries of the continent (Bujra and Adejumobi 2002: vii). To take only two examples, Liberia and Sierra Leone were the theater of two of the bloodiest civil conflicts of the 1990s (Reno 1998). In 2003, former warlord Taylor — under strong international pressure — stepped down as president of Liberia. In 2005, Mrs Johnston-Sirleaf won free and fair presidential elections, becoming Africa’s first elected woman head of state. In 2011, she was pronounced joint winner of the Nobel peace prize for her “nonviolent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work.”4 In Sierra Leone, the 2007 presidential elections brought to power the opposition leader Koroma. The latter declared a policy of zero tolerance to corruption. This stands in sharp contrast to his predecessor Kabbah, under whom corruption was endemic (Wyrod 2008: 81–2). Presidents Johnston-Sirleaf and Koroma were reelected in 2011 and 2012, respectively. Today, Liberia and Sierra Leone are both cited by donors as examples not only of post-conflict reconstruction, but also of macroeconomic and governance reforms (Gariba 2011: 129).5 This pattern can obviously not be generalized to the whole continent south of the Sahara. Swaziland is still an absolute monarchy (Motsamai 2011), countries like Sudan and Somalia are still striving to put an end to civil war, and others like Equatorial Guinea are still ruled by a half-hidden autocratic ruler clinging to power and hoarding the country’s wealth for the benefit of a few. However, as the coming chapters show, change is currently taking place in some countries. This is important not only per se, but also because improved governance has been shown to have a strong positive impact on economic growth (Kaufmann and Kraay 2002).6

The central question asked in this book is under which conditions is a country likely to progressively introduce genuine governance reforms? This question can be logically dissected into smaller questions. Which domestic actors have a positive impact on governance in a particular country? Can international actors have a positive impact? What is the relationship between international and domestic actors trying to push a good governance agenda forward? Is the influence of donors on government, if any, due to their financial leverage? Is it due to their normative power? What can explain cases of stagnation in governance? What can explain steps backwards? Is it true that oil exporting countries are unlikely to make governance reforms as the rentier state argument would indicate?7

The present book addresses these questions by studying the impact of international and domestic pressures and counter-pressures8 on governance reforms, for a sample of four very diverse Sub-Saharan African countries. The remainder of this chapter discusses the relevant literature, starting with a definition of governance, looking then at studies of possible independent variables on democratization and on the evolution of governance in Africa, and then borrowing a model from the field of human rights. This review shows the limits of the existing literature in simultaneously taking into account international and domestic factors on the one hand, and their possible contradictory influences on the other hand.

The second chapter introduces four hypotheses linking international and domestic pressures to improvement, stagnation, or deterioration in governance. The hypotheses are then systematically tested empirically over the four case studies, in chapters 3 to 6. The four hypotheses are largely corroborated by the four case studies. In the concluding chapter, a four-phase model is induced from the empirical data. This model, called the good governance socialization process, traces the evolution of African countries from a situation where a ruler’s support base fundamentally rests on poor governance practices, to a situation where good governance becomes progressively institutionalized in domestic practice, to such an extent that major deterioration becomes unlikely. Depending on the configuration of pro- and anti-governance pressures, the model also explains cases of stagnation and of steps backwards in governance.

Defining governance

Good governance refers to the respect of principles of participation, transparency, accountability, fairness and efficiency in “the formation and stewardship of the formal and informal rules that regulate the public realm” (Hyden and Court 2002: 19, 27).9 Building on this definition, governance reform refers to changes in the way that formal and informal rules regulating the public realm are formed and stewarded, with the aim being to increase participation, transparency, accountability, fairness and/or efficiency.

Governance is, hence, a broad concept. In a country which initially scores low on all five dimensions, the task of improving governance for a ruler genuinely committed to it is thus enormous, and can only be achieved partially within a single presidential mandate. The objective of the present book is to trace the impact of particular pressures on reforms conducted under a specific ruler. In this regard, it is thus more relevant to observe the adoption and implementation of precise policies that the government has been pressured to undertake, than to refer to general governance indicators as the dependent variable. For example, if civil society demands free access to public documents (independent variable), the relevant dependent variable for this particular issue is whether a freedom of information act is adopted, and whether, once adopted, it is enforced in a way that effectively guarantees free access to relevant public documents.

Yet, while a ruler cannot be expected to improve all aspects of governance over a single mandate, if he is both committed and able to progressively conduct reforms, positive results should also be observable on at least some dimensions of general governance indicators.

Many existing indicators attempt to measure governance in some way — an estimated 140 in 2006 (Arndt and Oman 2006: 30). The most widely used are the World Bank Institute’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (Kaufmann, Kraay and Masturzzi 2009), and Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, the latter measuring only one aspect of governance — corruption. These two indicators have the advantage of aggregating a wide range of individual perception indicators and surveys, and hence to be based on an important number of observations. Moreover, being perception indexes, they have the advantage of focusing on de facto changes, as opposed to supposedly objective indicators which focus on de jure changes which may never be implemented (Arndt and Oman 2006).

However, governance being a multidimensional and highly complex concept, it is already very difficult for experts to give a fair evaluation of it in a single country. The task of providing a reliable yearly measurement of governance in each country of the world is thus gigantic. For one thing, such an indicator inevitably has to rely on country experts, or on surveys, and is highly dependent upon the sensitivity of respondents, as well as upon their country of reference. Moreover, as many experts working in international organizations, such as the World Bank, move from one country to another over time, these indicators can even lack comparability over time in a single country. As a consequence, none of the existing governance indicators provides a sufficiently reliable measure to be able to precisely evaluate how an individual country progresses from one year to another, or to be able to precisely rank countries of the world in a given year. As the authors of Worldwide Governance Indicators admit, the standard error is almost systematically greater than either the difference from one year to the next for a given country, or the difference between two countries which are relatively close in ranking (Arndt and Oman 2006; Kaufmann, Kraay and Masturzzi 2009: 17–22). Hence, governance indicators have to be taken for what they are — an estimate of a country’s quality of governance in a given year, which can give a primary indication, but certainly not a precise answer on a country’s quality of governance. Moreover, if a country’s level of governance slightly rises or diminishes after a year, it does not necessarily reflect a real improvement versus a decline in governance, as it can simply be due to the standard error. However, if indicators show an appreciable difference over several years, as well as big shifts in country ranks — differences that are higher than the standard error — it is then possible to be relatively confident that it reflects a real difference in the quality of governance. For more details, as well as statistics and figures on these governance indicators for Sub-Saharan African countries, and for the specific countries studied in this book, see Bachelard (2010b).

The Afrobarometer survey gives a good indication of a population’s general perception of their government’s performance in a given year; for instance, on the quality of democracy, on the president’s respect of the rule of law, and on the government’s performance in the fight against corruption. Unfortunately, the Afrobarometer is only available for selected years, and does not yet cover all Sub-Saharan African countries. The empirical chapters refer to certain Afrobarometer surveys, where available, to independently assess how populations perceive their government’s performance.10

Many authors or aid agencies use poor governance and corruption as quasi-synonymous. Governance is, however, much broader. Nye’s definition of corruption is probably the most widely used:

Corruption is behavior which deviates from the formal duties of a public role because of private-regarding (personal, close family, private clique) pecuniary or status gains; or violates rules against the exercise of certain types of private-regarding influence … This includes such behavior as bribery (use of a reward to pervert the judgment of a person in a position of trust); nepotism (bestowal of patronage by reason of ascriptive relationship rather than merit); and misappropriation (illegal appropriation of public resources for private-regarding uses).

(Nye 2005: 284)11

Corruption is therefore only one possible symptom of poor governance. A country which has high-quality governance — that is where transparency and participation of the population are high, where politicians and civil servants are accountable to the public and can ultimately be sanctioned not only through the electoral system (for elected officials), but also through an effective judiciary system — has little room for corruption. Although an inverse correspondence is likely, this does not mean that in countries where governance is poor, corruption is necessarily high. The present book is interested in the broader concept of governance. However, as pressures resisting reforms are more likely to occur against anti-corruption programs than against less politically sensitive elements of governance reform packages, the fight against corruption is one aspect closely analyzed in the four empirical chapters of this book.

It should be noted that considering corruption as necessarily bad for a country is a matter of debate in the literature. For instance, based on an economic rather than political analysis, Khan (1996: 14) argues that corruption is harmful if the post-corruption allocation of resources is economically less efficient or welfare promoting than the pre-corruption allocation. Corruption is beneficial in the opposite situation. Such an utilitarian understanding of an unlawful phenomenon is however extremely dangerous. In a situation where corruption increases a country’s welfare, the reason may be that the laws of the country do not fulfil their intended purpose, in which case the laws ought to be changed through a democratic process. Alternatively however, the laws may be aimed at promoting goals other than pure economic welfare, such as social or environmental protection. In both cases, economic welfare should not be used as an argument to justify circumventing the rules through corrupt practices, as this jeopardizes the democratic system as a whole.

Governance and democracy

This book focuses on governance reform, not democratization. The two concepts are however so closely linked that it is impossible to study governance without discussing how it relates to democracy. Two opposite tendencies exist around the use of the concepts of governance and democracy. One the one hand, the two concepts are often used as quasi-synonymous both by scholars and international aid agencies — referring implici...