![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Colin Adams

The purpose of this volume is to explore connected themes on geographical knowledge and travel in the Roman world. It is a growing field, built upon much existing scholarship, and new evidence is coming to light which might revolutionise our understanding of how the Romans viewed the world in which they lived and how they travelled in it. The recent discovery on papyrus of what might be the only ancient map from the Roman period will certainly add complexion to this.1

The chapters are founded upon a series of five papers delivered by Adams, Brodersen, Coulston, Kolb and Laurence at the 1999 Roman Archaeology Conference in Durham, to which Salway’s paper has been added. The richness of the subject of transport and travel finds further reflection in the different approaches used by the contributors, and by the different forms of evidence, literary, epigraphic, papyrological, iconographic and archaeological, which form the basis of their papers.

Travel and communication are dynamics which were central to the Roman empire. Its sheer size and diversity demanded that there was an efficient system of communication in order for government to take place. This is not something which can only be seen with hindsight – Roman writers recognised the importance of communication, as we can see from a well-known passage from Aristeides of Smyrna, in which he recognised the Roman ‘world-state’:

Could not every man go where he wished, without fear? Are not all harbours busy, are not mountains as safe as cities? Is there not charm in all fields, from whence dread has vanished? There are no streams impassable, no locked gulfs. The earth is no longer iron, but clad anew for a feast. Hellenes and barbarians may wander from their own homes to arrive at their own homes; the Cilician Gates, the narrow sandy roads to Egypt through Arabia present no terrors of mountain pass, torrents, or savages: to be the emperor’s subject, to be a Roman is the one talisman. Homer had said, ‘The earth is common to all’; it was now realised. You have measured the earth, bridged the rivers, and made roads through the mountains, and ennobled all things. The world need be no more described; no laws or customs retailed; for you have been the leaders for everyone, have opened every gate and given every man his freedom, to see all with his own eyes. You have conferred equal laws on all, and repealed conditions entertaining to the mind, and intolerable in reality; and merged all nations into one family.2

This speech was delivered in honour of the first Antonine emperor and is clearly thick with eulogy. However, it illustrates the importance of communication on a number of levels. There was a civilising force – the idea that Roman citizenship was a unifying state. But more than this, the Romans had provided the means for the world to be common to all.3 Roman imperialism, displayed in the control of populations and the Romanisation of peoples, was also imposed upon the earth itself.4 Land was measured and divided, rivers bridged, canals dug joining rivers and seas, and roads were cut through inhospitable country.5 It became easier to travel – the long journeys made by envoys during the Hellenistic period, which were so fraught with danger and uncertainty, now became much easier and safer. Roman authors boasted of the pax Romana and the eradication of piracy and brigandage throughout the empire. This encouraged trade and transport, and Rome became the centre of this communication.

But was this new-found mobility something which affected all Rome’s subjects; who were the travelling public? And how was communication organised? How did people know how to get from A to B? Did maps exist, or did itineraries serve as route-finders? Was it possible to find one’s way, for example, from Rome to Brundisium, or from Antioch to Ephesus, using an itinerary in rather the same way as we might use a London Underground map or simplified plan for tourists that highlights the ease of travel to a place. Brodersen and Salway discuss these questions in detail, developing the fundamental work of Dilke.6

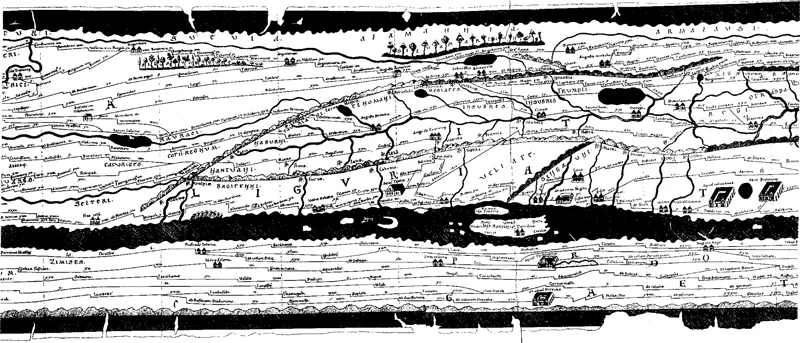

Brodersen surveys the existing evidence for ancient maps, and concludes that there is not enough to be certain that Romans had scale maps, or indeed needed them. Itineraries provided the information necessary for travel, and he compares this to modern road maps, which merely provide information on routes and junctions, but still permit efficient travel. Itineraria adnotata (annotated itineraries) provided enough information to travel along one route; itineraria picta (illustrated itineraries), such as the Peutinger Table or the recently discovered Artemidorus papyrus, permitted travel along any number of routes to several destinations. This interconnection of road systems, and indeed the fact that road, riverine and sea travel were all part of a complimentary system, is central to the work of Laurence on Roman Italy.7 Salway argues that inscriptions should be seen as complementary to such itineraria, and with this in mind we should not ignore a letter of Pliny the Younger, who discusses the importance of roads and milestones in gaining directions to people’s property.8 In the case of the Peutinger Table, he suggests that placenames are important to our understanding of it as a tool for travel, and as such, it belongs fully to the itinerary tradition, rather than a distinct pictorial one. The Peutinger Table comes from a single pictorial tradition, but the information preserved on it derives from itineraries. These latter derive from disparate and different sources; not from government sources, such as the cursus publicus, but from more public data displayed on milestones and tabellaria, which he argues are lists of stages and distances, and from information derived from survey and road-building.

Figure 1.1 Peutinger Table: section showing southern Germany, northern Italy and Numidia (after K. Miller, 1887). (With permission from the Österreichische NationalBibliothek.)

It is difficult to accept, however, that the government and cursus publicus did not have information concerning travel available to its officials. The communication infrastructure formed the backbone of provincial government. The imperial period saw a huge leap forward from the seemingly independent provincial governors of the republic, to a far more centralised system of government illustrated by Pliny the Younger’s correspondence with Trajan. Such themes form the basis of the work by Kolb, and her chapter here considers the role of the cursus publicus or imperial post service. There are clear links between this and the development of itineraries which have been preserved. It is fair to say that the road network of the empire served the needs of the state, both administrative and military, before those of private individuals; but the latter could certainly benefit. Adams shows that considerable numbers of travelling officials and soldiers could have used mansiones, the staging posts of the cursus publicus, at any one time, and there is good reason to believe that there was a significant amount of communication around the empire. Given this, it is likely that officials had access to information to facilitate their journeys, but Adams suggests that this information existed for another significant purpose, the administration of funds available to officials to pay for their travel. In other words, as well as providing information for travellers, itineraries served an additional fiscal purpose.9 Travel and communication permeated all levels of state bureaucracy, the fiscal sphere, and military logistics and organisation.

But the effect of communication could be felt more broadly. Laurence uses the infrastructure of communication within the Roman province of Britain as a measure of urbanisation and settlement geography. Our understanding of this is important, as Britain lies outside the centre of the empire in the Mediterranean basin, and thus may serve as a guide to the development of communication networks of frontier regions or those newly annexed. Evidence for mobility, Laurence argues, can be used as a measure of cultural change – and this is encouraged by communication with the centre of the empire – the idea of connectivity.

Recent work has illustrated how much the army and its commanders depended on communication networks within and without the empire.10 Such a reliance clearly extended to logistics.11 Coulston approaches the issue of military logistics and transport using iconographic evidence. Trajan’s Column (Figure 1.2) must be seen as part of the growing imperial necessity to advertise achievement – it was propaganda in its truest form, celebrating the glory of Rome and the emperors – but also of depicting Roman control and influence over the earth.12 The column represents the first depiction of military transport in Roman art, but is central to the imperial message that soldiers, and perhaps also the Roman viewer, were the emperor’s partner in the conquest of peoples and land. Technical skill is shown as a way of dominating peoples and lands, and this was evident to inhabitants of Rome. The great imperial building projects of emperors like Trajan and Hadrian utilised the resources of the whole empire. In the case of the Pantheon, for example, column shafts of Egyptian granite were transported from the quarries of Aswan and the Eastern Desert (Figure 1.3). In this way the Romans took the monolithic culture of Egypt to a new level, and superseded the pharaohs in their technical abilities.13

Figure 1.2 Trajan’s Column. Photograph R. Laurence

Figure 1.3 Pantheon. Photograph R. Laurence

The chapters here collected discuss themes of central importance to our understanding of the Roman world. These themes are crucial in that they show how mobile a culture the Roman empire was or had a potential to be. In this respect they show how far the discussion of mobility has come from the seemingly entrenched theories of Finley – a static population hemmed into local communities by the high cost of land transport.14 Rather, horizons had been opened up under the Romans to such an extent that...