This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Laos - the Lao People's Democratic Republic - is one of the least understood and studied countries of Asia. Its development trajectory is also one of the most interesting, as it moves from state, or perhaps more appropriately subsistence, to market. Based on extensive original research, this book assesses how economic transition and marketisation are being translated into progress (or not) at the local level, and at the resulting impact on poverty, inequality and livelihoods. It concludes that the process of transition in fact contributes to the growth of poverty for some people, and shows how people manage to cope in very unfavourable circumstances.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Living with Transition in Laos by Jonathan Rigg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Conditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 Managing and Coping with Transitions

Setting the Scene: Structures and Agencies

This is a story of mixed fortunes and unforeseen outcomes, of structural rigidities and surprising levels of agency. In other words, the story fits the template of many recent studies of social and economic transformation where neat transitions and clear trajectories of change are replaced by muddle and ambiguity. This is in danger of becoming the lazy conclusion of much social science research: the world is a confusing place of contradictory evidence and mixed messages; so why bother to make sense of it?

However, more often than not, there are patterns in the confused mosaic of human responses. At a base level there are commonalities, points of intersection in the propelling forces and driving desires that mould the human landscape. In their totality, people and households are joined, however loosely, in a shared wish to improve their lives and, more particularly, to improve the prospects for their children. There are shared goals that are defined increasingly in terms of ‘modernisation’. This is no reason to succumb to the notion that, in time, the world will converge on some common point as differences are worn flat by the indefatigable forces of globalisation. But it does indicate a need to scratch through the layers of muddle.

In writing these two paragraphs – and I do so having written much of the rest of the book – I am in danger of raising the unlikely possibility that I will say something truly profound. The argument which follows is more pedestrian and prosaic than that. In essence, it tries to tread the thin line between structure and agency, and does so in two ways.

The first resonates with Giddens’ structuration theory to the degree that I am interested in the ways in which – in practice rather than in theory – households and individuals challenge and rework the status quo. This may be in terms of ‘how’ people make a living in a country which is undergoing the transition from subsistence to market, and from farm to non-farm. Or it may be in terms of the software of change: the desires and aspirations that inform strategies of making a living and the negotiation (and resistance) that arises as established norms are stretched, reworked or reconstituted. The second reason I am interested in the structure/agency debate regards the distinction between the broader patterns discernible from the aggregate social and economic data, and the eddies that make these flows more complex and contingent than is sometimes assumed. As later chapters will elucidate, while there are common themes, these are worked out in sometimes surprising ways. It is possible – and often valuable and necessary – to squeeze individuals and households into none-too-neat categories (rich, poor, middle) and classifications (chronic, upwardly mobile, entrenched), but each time a generalisation is drawn the particularities of place and peculiarities of individual experience serve as a reminder that generalisations usually stand and fall by their utility, and not by their ability to explain the world. Bebbington notes that all processes are place-based, but they are bound up in the wider geographies of capitalism (2003: 301). Theory, in his view, needs to begin with place (and, I would add, circumstance) and then ‘build’ or ‘theorise’ upwards. Thick description based on ethnographic research is a good beginning, but it is not the end when it comes to elucidating geographies of development.

Laos

This book is, essentially, a discussion and analysis of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic’s engagement with modernity through its ongoing and evolving engagement with the market. The focus, however, is very much on the local and the human with an emphasis on how change is experienced at the local level. A geat deal of attention has been paid in recent years to what is variously termed the ‘everyday’, the ‘banal’, the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘prosaic’. This reflects two desires. First, and more obviously, a wish to shake off the dominating effects of the higher reaches of social, economic and political control and action; second, and less obviously, to focus concern on the normal times that link abnormal events. In this book too, the commanding heights of political and economic debate in the shape of ministerial meetings and national development strategies give way to a primary concern for communities, households and individuals and their lives. These are the starting points, even if the discussion and analysis may originate or terminate, occasionally, at a comment on some grand policy initiative.

In addition to being a study of contemporary change in Laos writ small, I set out to achieve something rather wider: to illuminate the rich terrain of struggle, resistance and acquiescence that is part-and-parcel of any modernisation project. This is not to suggest that the experience of modernisation is necessarily negative – far from it – but to recognise that change involves frisson no matter what the outcome of the process. ‘Frisson’ is used here to encapsulate those environmental, social, cultural and economic tensions that arise when established systems of production, consumption, reproduction and relation are challenged. In these regards the book is intended to provide an insight into such tensions and their outcomes. The stage for this act just happens to be Laos.

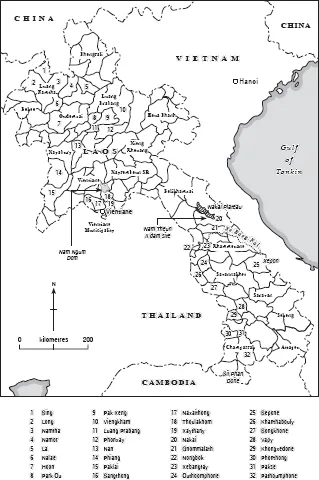

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Figure 1.1) is counted among the world’s forty-nine poorest countries. It is also situated within one of the world’s most economically dynamic regions, straddling Southeast and East Asia. Since the dark days of the war in Indochina and the country’s failed attempt at socialist reconstruction and development, Laos has been opening up in two regards. It has embraced, since the mid-1980s, a deep and far-reaching process of economic reform in the guise of the New Economic Mechanism (NEM) and, in 1997, the country joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean). Laos, in these two ways, has moved into the economic and political mainstream. The ruling Politburo may still rule, but it does so, it would seem, having given up the struggle of swimming against the current of economic history.

Figure 1.1 Map of Laos

That Laos is in transition is without question. The waters become increasingly muddied and muddled, however, when this question is dissected and interrogated. Transition itself is a nom de clef of every country, so what is meant – substantively – by transition when it is applied to Laos? Transition from command to market, from subsistence to market, or from self-reliance to dependency? Even more pertinent in a country where more than one-third of the population are recorded as living in absolute poverty, what are the livelihood effects of this process of ‘transition’? To put it starkly: What is the landscape of winners and losers and, moreover, how is this changing over time? This is not just a numbers game. It is not just a question of measuring the incidence of poverty over time but also, and more importantly, of understanding who is poor and why, and who is (relatively) rich and why. As this book will illustrate and argue, the ‘who’ and the ‘why’ change over time as transition proceeds. The rules of the game, so to speak, are in flux.

Building the Argument

The book draws on a combination of primary fieldwork and the analysis of secondary sources. The fieldwork, funded through an EU research grant,1 was undertaken over three periods during 2001 and 2002 in nine villages across three districts: Tulakhom district, 60 km north of Vientiane in Vientiane province; Sang Thong district, 60 km west of the capital on the Mekong, in Vientiane municipality; and Pak Ou district, 30 km from Luang Prabang in the northern province of Luang Prabang (Figure 1.2). In addition to these periods of fieldwork, a longer stay in Vientiane from the beginning of 2003 (also EU funded) permitted the collection of additional, secondary material.

Figure 1.2 Map of primary research sites

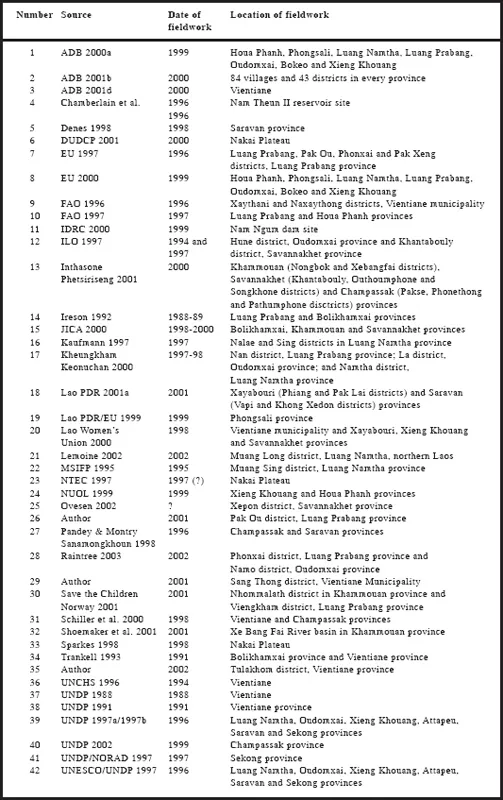

The approach to the fieldwork was participatory and used a range of qualitative methods. In summary, these included key informant interviews, transect walks, group and focus group discussions, participatory mapping exercises, life histories and time lines, and household case studies (see Plates 1.1–1.4).2 In total, across the nine villages, fifty-five case study households were selected for detailed interview as part of the project.3 In addition to this primary material, I also refer to a substantial number of unpublished and published documents. More particularly, the argument and underpinning discussion draw on data and analysis from some forty-two field studies, the great majority of these based on fieldwork conducted since 1995 (see Table A1.1).

Plate 1.1 Household interview, Sang Thong district (2001)

Plate 1.2 Participatory mapping exercise, Tulakhom district (2002)

Plate 1.3 Drawing a time line, Tulakhom district (2002)

Plate 1.4 Preparing for a group discussion, Tulakhom district (2002)

In the late 1980s, when the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) began to intensify their presence in Laos, it was still possible to write that even basic information about the country constituted ‘educated guesses rather than confirmed facts’ (World Bank 1990a). There was, the international aid community asserted, ‘insufficient information on the country’s key physical, social, economic and climatic variables’ (UNDP 1990: 9). Today, many of these basic knowledge gaps have been filled but, even so, the country remains one of the least understood and studied in Asia. Compared with other countries in the region, there are few scholars writing about Laos for an international audience and this applies particularly to work that requires some level of ground-level engagement. This is partly because of the difficulty, until fairly recently, of undertaking fieldwork in the country and partly, to put it bluntly, because of the country’s low international profile and significance.

While it may still be possible to depict Laos as ‘under-researched’, such a statement tends to overlook the rich grey literature that exists in government departments and in the offices of international agencies in Vientiane. Since the 1970s, and particularly since 1990, a large number of research teams have produced an even larger number of mission statements, midterm evaluations, feasibility studies, think pieces, project assessments, issue papers, aides-mémoire, briefing papers, appraisal reports, working papers, inception reports, baseline surveys and inventories, the majority in English and French. Small print runs of these documents are circulated among the international community in Vientiane to then languish, largely unread, in resource centres and libraries in the capital. It is this surprisingly rich seam of literature that I have mined to help underpin the discussion which follows.

The great majority of these ‘publications’ are not academic studies. Their raisons d’être usually lie, understandably, in the requirements and demands of development policy and practice, and they therefore have to be used with a degree of care. Yet they contain a wealth of information and data that are relevant and of interest to an academic study such as this one. In particular they provide two things. First, they provide a very extensive source of primary data on human development drawn from field studies – admittedly of varying levels of intensity and employing different methods – undertaken in all regions of the country (Figure 1.3). Second, they provide a direct link between policy concerns and interventions and actual and projected outcomes on the ground.

Figure 1.3 Map of research sites drawn from secondary sources noted in text; see Appendix 1, page 198, for further details.

Most of what we know of Laos – and the same may be said of other places too – comes from ‘grand’ studies that aggregate data to arrive at a generalised view of conditions. But as Ravallion (2001) has observed, the concern to arrive at easily digestible ‘averages’ tends to iron out differences. It is on this basis that Ravallion writes of the ‘importance of more micro, country-specific, research on the factors determining why some poor people are able to take up the opportunities afforded by an expanding economy … while others are not’ (2001: 1813). Such fine-grained studies permit some departure from the tyranny of averages. In this way, the ‘market’ becomes an agent for accumulation and impoverishment, while ‘social capital’ can be both developmental and destructive.

In focusing on the local and, in particular, on communities, households and individuals, new and different – not just more finely grained – perspectives become evident. An IDRC study of the Nam Ngum watershed, for instance, revealed that a traditionally sustainable system of resource management was undermined in the 1970s and 1980s as new settlers, with their own resource management traditions, began to settle in the area (IDRC 2000: 2). However, it was not a simple case of a sustainable system coming under pressure through a combination of resource pressures and the encroachment of new (unsustainable) systems. ‘The greater the level of detail we look[ed] at,’ the report states, ‘the more problematic gross generalizations and simplifications appear[ed]’ (IDRC 2000: 2). There were 200 villages within the watershed comprising Thai Phuan, Hmong and Khmu, ‘each group [with] different cultivation and resource management traditions ranging from wet-rice cultivation to shifting cultivation’ (IDRC 2000: 2). Applying single perspectives even in this restricted area would fail to illuminate the degree to which each group was facing different challenges and was responding to those challenges in different – but potentially equally valid, sustainable and productive – ways. In other words, the concern with the local reveals a different architecture, and not just the same patterns but at a finer level of analysis.

The research superstructure around which the book and the argument are formed consists, therefore, of two principle elements: primary field research, complemented by material gleaned from secondary, usually grey literature. These two strands of material are integrated into the discussion although the former are concentrated in the second half of the volume and the latter in the first half. In addition to these two lines...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations and terms

- 1. Managing and coping with transitions

- Part I: Setting the context

- Part II: Constructing the case

- Part III: Putting it together

- Notes

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index