![]()

Part I

The Cultural Politics of Public Health Scholarship and Policy

![]()

1 Deconstructing Behavioural Classifications

Tobacco Control, ‘Professional Vision’ and the Tobacco User as a Site of Governmental Intervention

Michael Mair

Introduction

One of the hallmarks of the ‘new public health’ is a programmatic concern with the part played by human ‘behaviours’ in the aetiology of illness and disease. Tobacco (mis-)use, alcohol (mis-)use and the complex of factors implicated in obesity are among its most prominent concerns. As understandings of the extent of the causal role of these ‘problem behaviours’ in disease and illness processes have improved, pressure has grown to find ways of doing something about them, to devise new forms of public-health intervention best suited to the specific challenges that these particular behavioural loci pose. In light of the stress placed on the behavioural dimensions of health and illness, it is unsurprising that public-health programmes in each of these areas, despite their many differences, often share a common purpose and design, typically aiming at the ongoing regulation and control of the behaviours in question; ‘prevention’ where possible, ‘containment’, ‘treatment’ and ‘modification’ where not.

Although much of the conceptual framework has been carried over, in grappling with ‘the behavioural sphere’ and attempting to encompass it within its legitimate domain of inquiry, the new public health – epidemiology in particular – has had to stake out a territory, intellectually and practically, that extends far beyond that which its nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century predecessors were in a position to lay claim to. Its empirical targets, its central objects, have changed, as have the key questions asked about them. The priority of contemporary public health is not simply to isolate behavioural factors such as smoking, drinking or overeating, and to look at the ways in which they causally connect to specific forms of illness and disease. Although the underlying physiological mechanisms remain an ongoing research concern, the important development has been a general shift in focus to treating the behaviours themselves as epidemiological phenomena, the problem becoming how to develop ways of isolating their causal antecedents, the ‘risk factors’ which increase the likelihood that (groups of) individuals will ‘contract’ those behaviours and so expose themselves to otherwise avoidable forms of harm.

In taking the ‘behavioural turn’, in other words, public health has made its business the examination of what makes individuals behave in ‘health-risking’ ways, the systematic investigation of the complex chaining of intertwined sequences of cause and effect that identifiably connect disease outcomes to a range of determinants, variously conceived (Mair and Kierans 2007). By embracing complex causality, by adapting the techniques of the social sciences, and by outsourcing the laborious technical task of matching pathogens to pathologies to research scientists in genetics, molecular biology and organic chemistry (Raymond 1989; Susser 1999), public-health epidemiologists have been able to leave the confines of the laboratory and move outside to survey, through the lens of behaviour, more and more aspects of the wider human world around them.

The goal in what follows is to explore some of the processes that have made this move possible, to critically examine how in practice the new public health goes about constructing its objects, here ‘health-related behaviours’, working them up in the particular ways that mark them out and give them their significance within its particular field of ‘professional vision’ (Goodwin 1994; Bowker and Star 2000). In an area of some complexity, I have found it helpful to focus in on simple, concrete examples in order to get a better sense of the sorts of processes and practices involved. Due to my background as a researcher within this particular sub-field and because I believe it usefully exemplifies what has been gained, what lost and what glossed over in making the ‘behavioural turn’, I have chosen to concentrate on tobacco use, more specifically, the mundane classificatory practices involved in the work of counting smokers.

Counting, Classification and Epidemiological Practice: The Case of Tobacco Control

While ubiquitous, counts are far from trivial (Cicourel 1964; Churchill 1966; Sudnow 1967; Sacks 1992; Bowker and Starr 2000; Martin and Lynch 2009). Quite the reverse; due to their simplicity, vernacular counting practices are powerful tools in all manner of ordinary and specialized settings. Within the pure and applied sciences, as the philosopher and historian of science Ian Hacking reminds us, the business of representation, defining a problem, and the business of intervention, acting upon it, are intimately related (Hacking 1983). And, in particular fields of investigation, the development of standardized methods of counting are central to that relationship as they prepare the ground for the stable systems of quantification and measurement that both rely upon (Lynch 1993). This is no less true of public health than it is of experimental physics. The practising epidemiologist, for instance, could not begin to get to work on a given health problem without methodical ways of charting that problem’s distribution, by distinguishing cases and then tallying them according to type (Lynch 1985). As elementary constituents of wider forms of public health and epidemiological practice, counts can thus be seen as part of what enables the whole enterprise to get off the ground, allowing epidemiologists to locate and fix in place ‘the objects of knowledge that become the insignia of the profession’s craft, … its special and distinctive domain of competence’ (Goodwin 1994: 606).

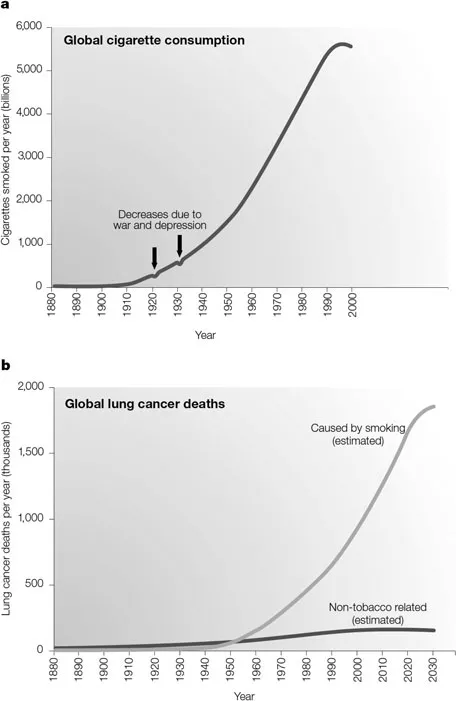

Counting smokers is a case-in-point. By choosing to include, in the data they collected, counts based on whether the lung-cancer patients within their samples were smokers or not, clinician-epidemiologists, like Wynder and Graham in the US, and Doll and Bradford-Hill in the UK, were able to make the connection between smoking and lung cancer. Their capacity to ‘see’ where smoking fit into the aetiology of a particular disease was thus shaped by the taking of counts and the binary system of classification those counts proceeded from; ‘being a smoker’ becoming the figure that was eventually highlighted against the otherwise undifferentiated ground of the case histories they were analysing (see, for example, Doll 1998; Susser 1999; Thun 2005).1 Graphic representations of the relationship these researchers uncovered, starkly unequivocal, continue to testify to the analytic power generated by organizing their results in terms of the crosstabulations that the use of this simple device permitted (see Figure 1.1). Whether the first to discover the relationship or not, it was this group of studies published in the 1950s, classics of biostatistical analysis and causal modelling, that was to have a decisive influence on public health in the latter half of the twentieth century. These studies brought the dangers of tobacco use to the attention of the post-war publics in North America, Western Europe and subsequently beyond, providing a spur to further and increasingly sophisticated scientific work, and helping, in the long term, to galvanize a global tobacco-control movement which now claims them as its originary texts. That researchers have yet to find something that produces quite as clear-cut a depiction of the relationship between exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and its impacts on health perhaps provides some explanation as to why it continues to be a live issue (see Tonks 2003; and Bell, this volume).

Figure 1.1 Tobacco consumption and global lung cancer deaths (reprinted with the permission of Nature Publishing Group).

Sixty years after the publication of those studies, counts of the number of smokers in a given population remain the basic source of raw data upon which responses to the problem of tobacco use are based. In that time, tobacco control, like other areas of public health, has become an increasingly data-intensive enterprise, and its sophisticated population surveillance and monitoring systems are reliant on the continuous flow of massive amounts of information from and through the local, national and international ‘centres of calculation’ that represent the key institutional relays in its global architecture (Latour 1987). Given this, it is unsurprising that the World Health Organization (WHO), which presided over the construction of that architecture and plays a crucial part in coordinating action on tobacco control, emphasizes the importance of the collection of ‘good’ local counts, data which it regards as the essential building blocks of an accurate ‘composite picture of the status of the tobacco pandemic in the early 21st century’ (WHO 2003a). The WHO’s landmark Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which became one of the most widely assented treaties in UN history when it was passed into international law in 2005, includes a section that deals exclusively with ‘scientific and technical cooperation and the communication of information’ on the question of tobacco use (2003b: §VII). That section of the treaty, among other things, requires signatories to:

establish, as appropriate, programmes for national, regional and global surveillance of the magnitude, patterns, determinants and consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke … so that data are comparable and can be analysed at the regional and international levels.

(WHO 2003b: 20.2)

Beyond publicly marking a foundational normative commitment to tobacco control, the extensive tables of information that are produced by these surveillance activities allow health officials to profile smokers in increasingly detailed ways, equipping them with a visualization device, an ‘optic’, that provides not only a view of the population as a whole but also the capacity to zoom in on particular ‘at-risk’ groups and deliver interventions in finely targeted ways. The biopolitical rationale that guides statistical surveillance of this kind, its general role in making populations manageable, has been examined by a number of celebrated researchers and social theorists, and requires little additional comment here (see Foucault 1975, 1998; Hacking 1990; Porter 1995; Scott 1998). What is worth initially emphasizing here, a specific instance will be discussed in more detail below, is the way in which this particular conception of research-ascounting ties directly into a particular logic of intervention. On the WHO’s model, intervention, of which surveillance is an integral part, involves an open-ended commitment to further action (Hardt and Negri 2000). Although the problems it is addressed to may change over time, with crisis-management giving way to monitoring and prevention once problems are brought under control, ongoing action of some sort, appropriately modified to take account of the numbers, will always be necessary. Vigilance must be constantly maintained.

In relation to some problems – the great infectious diseases spring to mind – such a stance is clearly warranted. However, it becomes much more problematic, as is the case with tobacco use (not to mention alcohol use and obesity), when the ‘disease’ in question is no sort of disease at all but an activity linked to the way certain delineated categories of people live their lives (see Gard and Wright 2005). Here, intervention has a tendency to become highly intrusive, selective and discriminatory, and can serve to reinforce the marginalization of the already marginalized (see Salmon, this volume). When the same ‘problem’ populations are picked out time and time again, on behavioural grounds, for the purposes of intervention – indigenous peoples, the urban poor – they come to inhabit what Hardt and Negri term, following Agamben, a de facto ‘state of exception’ in which they are partitioned off from the rest of ‘healthy’ society in terms of the differential treatment they receive (Hardt and Negri 2000: 17). Routinely re-describing activities that individuals engage in, like smoking or any other ‘risk behaviour’, using the language of the epidemic, has been one of the ways in which this partitioning has been practically achieved (LeBesco, this volume; Lavin and Russill 2010).

Behavioural epidemiology’s practices of counting, exemplified in the WHO’s programmatic ambitions for tobacco-control research, have, I would suggest, been central to recent shifts in the conception of public health’s proper aims. The mundane work of counting smokers thus matters, and it matters for a range of reasons, providing, as it does, a means of mapping out particular kinds of problems, classifying particular populations and framing particular types of interventions. It contributes towards making tobacco use, and tobacco users, public, accountable and actionable concerns. There is, therefore, a great deal that we can learn by looking in detail at what that work involves.

As part of its drive to establish a global system for accurately measuring the spread of the ‘tobacco pandemic’, the WHO has encouraged the adoption of a universally standard method, examined below, based on a set of criteria that rigidly define what is to count as a smoker and how. The WHO’s claim is that this system of quantification, which is able to weave together the local and the global in an apparently seamless web, is a neutral apparatus for ‘carving the world at its joints’, laying things out as they are in themselves before the gaze of dispassionate observers. However, establishing criteria about what is to count inevitably brings out some features of a phenomenon while excluding others, incorporating them within systems of relevancies that have important implications for the way in which it is possible to access and so think about the nature of the problems they are used to describe (Law and Lynch 1988; Goodwin 1994; Bowker and Starr 2000): numbers do not determine their own significance. Counting, in this sense, has a politics, what Martin and Lynch (2009), adapting Hacking, have termed a ‘numero-politics’.

Once ...