![]()

Part I

The Realities of Working-Class Life

Because working-class life is frequently either ignored or caricatured in the United States, critics of working-class literature often focus on unearthing working-class writers’ representations of the lived experience of class. These imaginative reconstructions of working-class lives reaffirm suppressed histories for working-class audiences and challenge middle- and upper-class readers to recognize the tangible effects of class inequity.

Paula Rabinowitz, in a move signaling our increased awareness of the importance of visual culture, examines both literary and photographic landscapes of economic depression. In writing about literary and visual texts about the Great Depression, she examines the physical places of poverty, such as the Hoovervilles that were built along roads, as well as the displacement of families who were uprooted from their homes or jobs or both. Rabinowitz also examines contemporary work on the Great Recession, which is characterized by abandoned homes and industrial buildings left shuttered and crumbling. Such places are repositories of memory: memory of community and a time when middle-class comfort was within reach.

Whereas Rabinowitz examines representations of how economic crises alter people’s physical and psychic landscapes, Renny Christopher’s article underscores the danger inherent in working-class jobs. I use the word “inherent” with some hesitation, for while much blue-collar work may be more risky than white-collar desk jobs, Christopher notes that the United States has a high rate of work-related injury relative to other industrialized nations. The numerous industrial, agricultural, and other accidents that occur in literature are violent and, as readers of texts such as Pietro di Donato’s Christ in Concrete can attest, difficult to read. Christopher, in her study of numerous novels and poems, thus compares the challenges of writing about work-related accidents to the challenges of writing about combat casualties: she asks how a writer can render the realities of horrific accidents and deaths without being sensational or “pornographic.”

Sylvia J. Cook also takes up a work-related question that has horrific dimensions: slavery. Cook, however, begins with the question hotly debated by literary critics and labor historians as to whether slaves should be considered part of the working class. In her examination of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Cook argues that each author put class at the center of her narrative. The centrality of class does not suggest that class is more important than race, which would certainly be a peculiar formulation in an abolitionist novel, but rather suggests how class and race may be interlocked and how this intersection is understood by the protagonists. In showing how slaves in both texts adapted nineteenth-century codes of respectability and refinement, as well as instances of both identification and tension with poor whites, Cook emphasizes the complexity of the questions and advocates for reading these texts as “resources” that help us to understand rather than as “symptoms” that point to problems with ready diagnoses.

![]()

1 “between the outhouse and the garbage dump”

Locating Collapse in Depression Literature

Paula Rabinowitz

Kenneth Fearing, Dead Reckoning

Flying by the seat of one’s pants, guesswork because the instruments have failed, the stars cannot be sighted, one’s location unfixed. It was the title of Kenneth Fearing’s mid-Depression volume of poems—a navigational term of unknown origin describing the method of plotting a course based on past positions. Because space and velocity are relative—because the rug’s been pulled from beneath one’s feet, with each reckoning, the possibility for error increases exponentially. As such pathbreaking works by Caren Irr (The Suburb of Dissent) and Jani Scandura (Down in the Dumps) have shown, Depression-era literature was rife with tropes of positioning, of location, of place; or rather of displacement, derailment, missing locations, and missed connections. Spatial order—central to demarking borders between industrial and residential zones, between men and women, between workers and their bosses, between races, between parents and their children—although sharply visible, still tangibly in effect, could no longer be counted on to signify as they once had. Kenneth Fearing outlines this vanishing urban space “[b]etween the haberdasher’s and the pinball arcade,” a “heelpocked pavement” distinguished only by a cigarette butt in “Memo” (77).

In our current “Great Recession,” these “heelpocked” locations of collapse have become even harder to discern as they have extended beyond the cheesy cityscapes “between the haberdasher’s [if there any left in America] and the pinball arcade” across landscapes of subdivisions and big-box stores. The space of the “doubly occupied,” as anthropologist Kathleen Stewart calls it, “a space on the side of the road” (marginal areas where dispossessed people congregate and exchange hardship, survival, and other stories), at once controlled by forces beyond the locales in which people reside—military occupiers, industrial and financial giants—yet still remaining repositories of local forms of memory, desire, and imaginative rumination—and possibly even organization. In short, what were once “places,” suffering but iconic, during this current episode of depression known as recession, are now displaced, dispersed across an invisible terrain, “up in the air” where, as Frank Rich points out, the movie based on Walter Kirn’s 2001 novel dematerializes this site.

It was not until 1928, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, that the term “depressed areas” came into use to describe zones of economic devastation.1 Not that these locations of collapse were not obvious, and obviously cordoned off, before then. In the 1880s, following the English graphic artists (Samuel Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, Francis Montague Holl) he admired, Vincent van Gogh knew to sit before the poor houses and churchyards and potato fields to find the “orphan men,” those destitute old homeless men, he was drawing.2 In America, Dutch émigré Jacob Riis knew where to find “the other half” who lived crammed together in the Lower East Side of New York—the place where Michael Gold would later find “Jews without Money” living amid dumps and among bedbugs (a literary form that Michael Denning dubbed “the ghetto pastoral” [230]). Spatial metaphors limn class divisions—the topos is the trope.

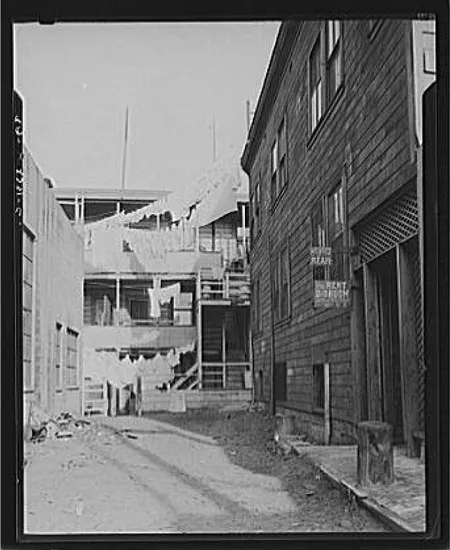

Figure 1.1 Dorothea Lange, “Slums of San Francisco, California.” June 1935. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF 34–002331-C.

Depression—a word dating at least to 1391 when Geoffrey Chaucer used it to describe the astronomical phenomenon of the lowering of a polestar or planet beneath the horizon—is literally a condition of being lowered in position. Pressed down, sinking, it refers to elevation or rather its opposite—structurally or figuratively—tracking horizons, fortunes, powers, affects: these more metaphorical and psychological senses emerge in the mid-seventeenth century and explode into the nineteenth century as surgery, gunnery, algebra, pathology and medicine, geology, musicology, philosophy, meteorology, finance, all begin to use the term to denote a lessening or lowering of or within.3 Codified as a psychiatric disorder only in 1905, it finally settles as the term for the Great Depression following the 1929 stock market crash and its aftermath, settles in part as a gentler antidote to the harsher nineteenth-century terms panic or crisis (Bird 89, qtd. in Dickstein 6). Thus the slippery usage of this word—a term of mobility itself—veers from the cosmic across an array of fields of specialization to eventually land in the interiority of the psyche and then extend outward again into the realm of economics. Contemporary usage toggles between the psychological and economic, though as our current euphemism of recession suggests, it’s now a term to be avoided—through infusions of Prozac or TARP.4 Yet the two modern meanings are so embedded within middle-class life they resist troping, or rather, they have become the trope—the “turn,” “manner,” “way” according to Webster’s Universal Encyclopedic Dictionary—in which we live, the figuration of this doomed location.

The Great Depression was figured as a collapse—literalized in Pietro di Donato’s 1939 novel, Christ in Concrete, as a collapsing building that smothers its workers alive under tons of debris—or as a massive flow of drowning workers migrating across regional borders to connect those passing along the edges of John Dos Passos’ 49th Parallel. Either trope—vertical instability and collapse or horizontally emptied spaces—made visible this ruin, a vision of diminishment, seen through predictable icons of men lined up along streets for bread or work (seen, for instance, in Dorothea Lange’s 1931 photograph White Angel Bread Line) or uprooted families strewn along dust-filled landscapes (found in Paul Taylor and Dorothea Lange’s American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, or Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White’s You Have Seen Their Faces, or James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men) or squatting in substandard housing zoned to contain impoverished immigrants and migrants, ethnically and racially marked as unfit or undeserving (seen in Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices). Its inhabitants, despite being found everywhere, were nevertheless sent to the corners and margins of visibility. As Miles Orvell has pointed out, this extended to bastions of capitalism: in “the first year of the depression … Fortune … devoted to stories about gold and wine, Macy’s and the Vanderbilts, the New York Times and the International Paper Company … [printed] an article called ‘Vanishing Backyards’, an article on junk. … America is likened to a child that recklessly ‘hurls its refuse out the window, and doesn’t care how high are piled the tin cans in the backyard’” (287). The connection between marginal spaces (backyards) and marginalized people (children) was firmly in place immediately after the crash.

Figure 1.2 Arthur Rothstein, “Squatters’ shacks along the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon. Many of the men living here during the winter work in the nearby orchards of the Willamette and Yakima Valley in the summer.” July 1936. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, LC USF 34–004831-E.

Tillie Olsen: Yonnondio

The “one patch of green”—“there was no other place for Mazie”—is found “between the outhouse and the garbage dump,” a zone suffused with “a nauseating smell,” but affording the child enough privacy to indulge daydreams (4–5). Throughout the rest of Olsen’s fragment of a novel, these two eccentric monuments (to shit, to trash)—especially the garbage dump at the river’s edge—sites of refuse, debris, waste, “places piled high with collections of used-up things still in use”—become refuges for the imagination of the “doubly occupied.” (Stewart 41, 61). This elision, from refuse to refuge, that sibilant s easing into a soft g, is a common thread of locating “a space of alterity,” according to anthropologist Kathleen Stewart as an entire ethos and aesthetics of “making do”—of dead reckoning—maintained daily life in these edge zones (Stewart 91, 68). As Mazie sinks deeper into lethargy and lassitude with each move across the destroyed landscape of midcontinental United States, the dump becomes a tangible location of her collapse—and a refuge from it.

What begins for her when she peers into the mouth of the pit mine and its fiery backdrop as a vision of hell—the depression below the horizon—extends briefly from her cramped and violent childhood in a Western mining camp out across a huge prairie landscape to encompass the stars lowering to its flat expanse. It quickly contracts again when her family’s financial disaster as sharecroppers leaves them mired in debt. But the city dump, down by the river bank, finally opens an exciting new space of exploration: “On the inexhaustible dump strange structures rise: lookout towers, sets, ships, tents, forts, lean-tos, clubhouses, cities and stores and train tracks, cabooses, pretend palaces—singularly fitted with once furnishings, never furnishings, or nothing at all” (150). Ultimately, this refuse refuge, this stagnant “space on the side of the road” congeals into a tomb for her listlessness: “Where you going?” “No place” (169). “And there was nothing really new on the dump. It smelled sewer, smelled garbage, smelled crap ’cept right at the river-bluff edge” (168).

“I don’t have no place. . . .” “Why don’t I have no place?” (178). Mazie finally confronts her mother who has tossed out—dumped—her homemade “perfume,” a stinking brew concocted for her dump girlfriend Ginella from scavenged flower petals rotting in a discarded and corked bottle. The entirety of Omaha becomes no place, a kind of refuse pile, circulating the smells of the slaughterhouse and pork processing plants, the dead riverbanks, at once empty and overripe. Susan Edmunds, commenting on the perfume scene, notes its debt to what she outlines in Grotesque Relations as “the domain of the domestic exterior” (125), especially as it was promulgated during the early 1930s by the Hoover administration, which she finds stressed through its publication The Home and the Child the importance of “proper disposal of garbage … the harmfulness of residences located ‘unduly near railroad … dumps, marshes, or obnoxious industries’” (137–38). And, this pamphlet goes on to insist, a la Virginia Woolf’s call for A Room of One’s Own a few years earlier, upon “‘privacy … each child should have a place’” (qtd. on 139).

In Yonnondio, Olsen delineates the...