This is a test

- 139 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Education, Racism and Reform (RLE Edu J)

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this introductory text the authors look closely at widely held assumptions about 'race' and schooling in Britain, and evaluate the role of the school in a multi-ethnic society. Focusing on contemporary issues and concerns, they consider such controversial questions as: Is the education system rigged against black pupils? Is 'tolerance' really a characteristic of the British? The volume provides a detailed analysis of the Education Reform Act (1988) and the debate surrounding the National Curriculum, and asks whether these new initiatives do truly open the doors of opportunity for all children.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Education, Racism and Reform (RLE Edu J) by Barry Troyna,Bruce Carrington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Anti-Racist Education: A Loony Tune?

As we enter the 1990s it is becoming increasingly obvious’ to a growing number of people that anti-racist education (ARE) is a ‘loony tune’ of the radical left; another antic of ‘the race lobby’ which, as the Daily Mail insists, flies in the face of ‘common sense’ (‘More anti-racist nonsense’, Daily Mail, 17 May 1989). Burnage High School in Manchester, Highbury Quadrant primary school in London, Brent, Dewsbury and the Inner London education authorities have assumed demonic status in the eyes of the anti-anti-racists. This group of critics is not confined to right-wing theorists and activists. On the contrary, its membership is expanding at an inexorable rate and largely transcends conventional left/right, professional/non-professional divisions in the educational community. Therefore, let us examine the objections to ARE. At the risk of over-simplification, they seem to crystallize around three discernible, if not entirely independent nor discrete, issues: its mismanagement and application; its principles; and its irrelevance.

The first objection figures prominently in the critiques of (some) radical and liberal commentators on ARE. For instance, James Lynch, a leading exponent of cultural pluralist ideas, castigates ARE for being ‘too political, confrontational, accusatory and guilt-inducing’ (Lynch 1987:x). The National Union of Teachers tends to agree. In its guidelines on antiracism in education, it concedes that there have been ‘insensitive applications of anti-racist policies in some areas’ (NUT 1989:1). Indeed, this constituted the main criticism in the report of the MacDonald inquiry into the murder of Ahmed Iqbal Ullah by a white pupil, Darren Coulbourn, in the playground of Burnage High School in 1986. Whilst the committee of inquiry voiced its support for policies to tackle racism in education, it criticized the senior management of Burnage for applying a simplistic model of anti-racism to the school in their forlorn attempt to manage the tensions that were generated by the murder. As the committee observed, ‘the application of a moral antiracism’ which assumes that all whites are racist was ‘an unmitigated disaster’ which exacerbated rather than defused tensions in the school (MacDonald et al. 1989). Along the same lines has been the assessment of how Brent LEA in London has proceeded to tackle racism in its local schools. The HMI reports into educational provision in Brent (HMI 1987) and, in the following year, the authority’s Development Programme for Race Equality (DPRE) (HMI 1988), alongside Sir David Lane’s report on the DPRE for the Home Office (Lane 1988), coalesce around criticisms of the vigorous, some might say philistine, way in which the LEA has attempted to put flesh on the bones of its anti-racist education policy. The dispute that centred on the alleged racist remarks made by a local primary headteacher, Maureen McGoldrick, in 1986, the setting up in the same year of the DPRE – a group of advisers who were typified in the media as ‘race spies’ – and the comings and goings of Directors of Education generated considerable and prolonged media attention and criticism. Reactions to the events at Highbury Quadrant school in Islington also fit into this category. The decision to hold an assembly there in July 1988 to celebrate Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday sparked off a chain of events which culminated in the ILEA deciding to remove experienced teachers from the school. Once again, this stemmed from a perception of overzealous involvement of the school’s senior management in implementing anti-racist policies. ‘The Highbury Quadrant teachers regarded antiracism as something they could teach through their militancy,’ insisted the Labour leader of the ILEA, Neil Fletcher. ‘As an authority we would reject that’ (Guardian, 13 December 1988).

Whilst these criticisms do not attack the legitimacy of ARE per se, there are those who have raised doubts about the efficacy of its principles and have questioned their relevance to the educational experiences of black (and white) pupils. This was expressed most vividly at the Conservative party’s annual conference in 1987. There Mrs Thatcher juxtaposed ARE with good’ education in her gratuitous claim that ‘Children who need to be able to count and multiply are learning anti-racist mathematics – whatever that may be’ (Thatcher 1987). Others have indicated, in less hysterical terms, that a concern with ARE might be diversionary, inhibiting rather than enhancing the academic progress of black pupils. For this reason, Malcolm Cross (1989) is critical of anti-racists who have mounted ‘thoughtless attacks’ on the National Curriculum. In his view, the revival of core’ subjects in the new legislation could provide a ‘window of opportunity’ for black pupils who, for one reason or another, have been deprived of the educational experiences that are enjoyed by their white, middle-class counterparts. Circumstantial support for Cross comes from an inquiry into the London borough of Newham, where examination results are notoriously low and where ARE features prominently on the educational landscape. According to the chair of the inquiry team, Seamus Hegarty, the LEA has given more attention to raising teachers’ awareness of racism than to meeting the needs of black pupils. Put another way, ARE has benefited white teachers more than black pupils, enhancing the career opportunities of the former whilst depressing those of the latter (Independent, 7 April 1989).

Criticism of the management, relevance and efficacy of ARE has thus loomed large in the campaign of vilification. None the less, the most trenchant objections to ARE have been voiced by those polemicists and theorists who are associated with the New Right. Since the mid-1980s, ARE has been subjected to unrelenting attacks by Anthony Flew, Ray Honeyford, the Hillgate Group, Frank Palmer, Roger Scruton, John Marks and other doyens of the New Right. They challenge the very raison d’être of ARE (see Oldman 1987). Their interventions have rested on two main predicates. First, in contradistinction to compaigners for ARE, they insist that racism is neither institutionalized nor normative in British society (e.g. Honeyford 1988). In other words, they subscribe to what we saw referred to earlier as the ‘rotten apple theory of racism’. Second, they perceive the function of schooling largely in instrumental terms. In this view, ‘the deterioration in British education has arisen partly because schools have been treated as instruments for equalizing, rather than instructing, children’ (Hillgate Group 1987:2). The educational (and social) policy that stems logically from a synthesis of these positions corresponds with interpretations of the liberal democratic tradition. The state should offer protection to individual liberties and therefore must try to ensure that black pupils are not subjected to explicit forms of racial discrimination and violence. In addition, the state, where necessary, should provide black pupils with the opportunity to become functionally competent in English. However, no other concessions are necessary and should not be offered. In short, black pupils should be treated as ‘trainee whites’. The assimilationist approach that this commends has characterized some of the responses to Muslim objections to Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. It will be recalled that, closely associated with fundamentalist demands for the banning of this book, there was a more forceful insistence, on the part of some Muslim community spokespersons, for separate schools. The media and public response demonstrated unequivocably that assimilationism, and the conditional citizenship for blacks which it implies, was once again in the ascendancy. As Woodrow Wyatt, ‘the voice of reason’ in the News of the World, put it to his readers:

newcomers here are welcome. But only if they become genuine Britishers and don’t stuff their alien cultures down our throats.

(5 March 1989)

Or as George Gale, ‘cutting through the nonsense’ and presenting ‘the voice of common sense’, informed his Daily Mail readership under the headline, ‘No room for aliens’:

we must do nothing through legislation or the use of public money to preserve alien cultures and religions. Likewise, they must seek to be assimilated. … They have chosen to dwell amongst us. In Rome, do as the Romans do.

(3 March 1989)

For those who have first-hand experience of the changing political climate in the ‘race’ and schooling debate, from the time when black pupils first began to make their presence felt in the UK’s schools in the early 1960s, the influence of the New Right’s conception of ‘the multicultural society’ on national and local policy in the late 1980s provides a sense of déjà vu: a flashback to the days, nearly thirty years ago, when ‘only if’ definitions of citizenship for black immigrants and their children prevailed. Consider, for example, the close resemblance between the views of Wyatt and Gale and those of George Partiger (former MP for Southall) who had this to say in 1964:

I feel that Sikh parents should encourage their children to give up their turbans, their religion and their dietary laws. If they refuse to integrate then we must be tough. They must be told that they would be the first to go if there was unemployment and it should be a condition of being given National Assistance that the immigrants go to English classes.

(cited in Troyna 1982:129)

Nor are the similarities confined to media discourse or political rhetoric. The re-emergence of assimilation as a credible and legitimate ideological base for the debate about ‘race’ and schooling can also be inferred from the framing of recent policy documents. Of these, the education development plan that was issued by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea springs to mind. In 1988 the borough declared its intention to abandon ARE principles and practices when it assumes responsibility for local services from the ILEA in April 1990. Its education plan, issued in early 1989, actualized this commitment. Thus, after a perfunctory acknowledgement of the borough’s duties under Section 71 of the 1976 Race Relations Act, which the borough conceives in the narrow sense of promoting ‘equality of opportunity’ rather than the broader commitment to ‘eliminate unlawful racial discrimination’, the plan proceeds to identify the ‘specific educational needs’ of ethnic minority pupils (Royal Borough 1989:49). However, these are defined in terms of, and confined to, language, with an assurance that the borough will help pupils whose mother tongue is not English to develop competence in this language. The value of mother-tongue teaching is also interpreted in these terms; namely, as a means to an end – the acquisition of English. The limited conception of ethnic minority ‘needs’ in the borough can also be inferred from the decision to locate responsibility for ‘multi-ethnic needs’, at inspectorate level, with the Inspector for Communication and to diffuse the concern for promoting equality of opportunity throughout the inspectorate without any indication of how this might be monitored (Royal Borough 1989:49).

The policy proposals of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea constitute a most spectacular retreat from ARE principles and interpretations. However, the borough is not alone. Other LEAs, such as Berkshire, Bradford, Inner London and Manchester, have demonstrated, in recent years and in different ways, a more hesitant and ambivalent commitment to ARE in particular and to egalitarian initiatives in general. Whilst colour-blindness’ has not been reinstated as a policy imperative in these LEAs, the radical approach to the formulation, implementation and appraisal of ARE, which characterized their procedures in the mid-1980s, is now a thing of the past (Troyna and Williams 1986).

The liberal moment thus seems to have gone. That moment started with the publication of the 1977 Green Paper, Education in Schools: A Consultative Document, where for the first time the DES acknowledged, albeit in the most tentative manner, the legitimacy of cultural pluralist conceptions of educational reform:

Our society is a multicultural, multiracial one and the curriculum should reflect a sympathetic understanding of the different cultures and races [sic] that now make up our society.

(DES 1977:41)

The pursuit of egalitarian reforms, especially from anti-racist perspectives, gained momentum with the outbreak of urban disorders in 1980, 1981 and 1985 (see Chapter 2) and ended, in our view, with the introduction of the Great Education Reform Bill (GERBIL) into the House of Commons in November 1987. We can now look back with some nostalgia on that period, which saw an increasing awareness of how racial and gender inequalities disfigure the educational life-chances of pupils and which encouraged a number of LEAs and their schools to promote ARE (and other egalitarian initiatives) as an integral and informing aspect of their policy and practice. Of course, we should not romanticize this trend; after all, there were some LEAs and institutions where ARE constituted little more than impression-management and the great divide between rhetoric and practice was never seriously broached, never mind breached (Troyna and Ball 1985). At the same time, it would be disingenuous not to acknowledge some of the important steps that were taken at local government level and in some schools and colleges towards expediting provision and resources for the development of strategic policies to combat racism (alongside other structural inequalities) and the practices to which they give rise.

The Shifting Sands of Ideology and Policy

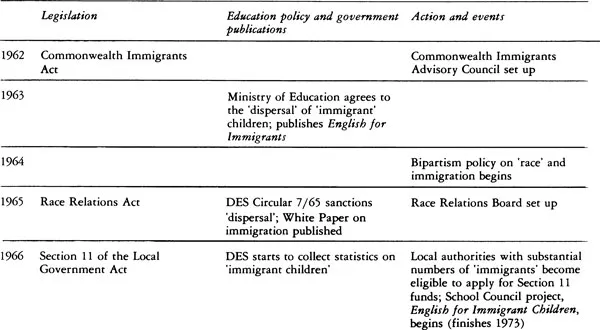

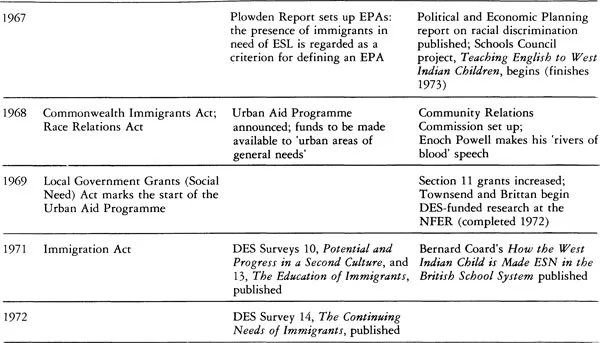

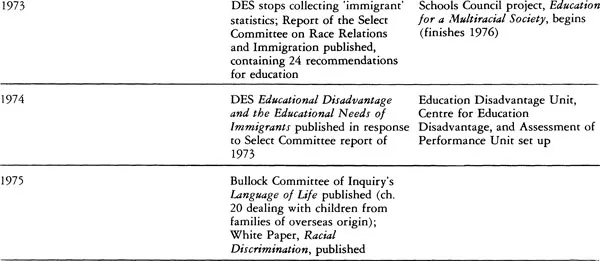

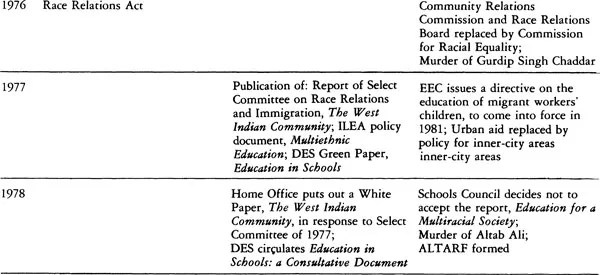

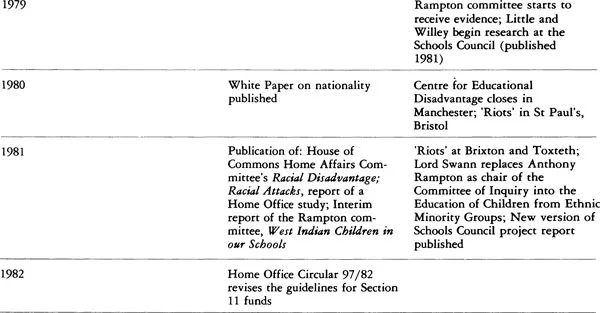

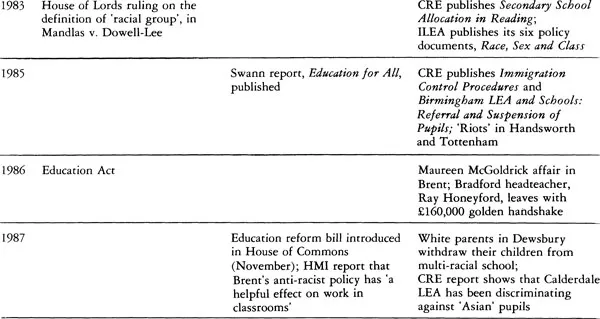

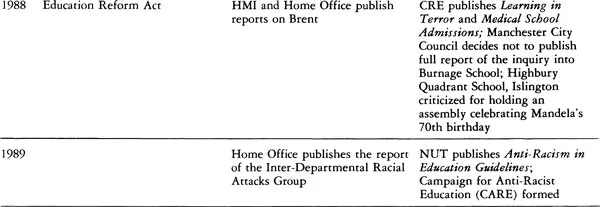

How do we make sense of the changing ideological and policy idioms in the ‘race’ and schooling debate? As Table 1.1 indicates, there has been a range of initiatives in this sphere of educational and social policy since the early 1960s and we have given some flavour of the rapidly changing ways in which the issues have been defined and, in some cases, confined. These ‘racial forms of education’, according to Chris Mullard, have assumed various guises: ‘immigrant’, ‘multiracial’, ‘multicultural’ and most recently, of course, anti-racist education (Mullard 1984:14). However, these labels tell us little about the political or educational principles which underpinned the policy and pedagogical approaches. It is important, therefore, to go beyond the historical narrative that is provided by Sally Tomlinson (1983) and the Swann committee (DES 1985a) and to consider the conceptual frameworks which social scientists have generated not simply to trace, but also to understand, the evolution of policy and practice on ‘race’ and education over the last twenty-five years.

Table 1.1 The educational response to black pupils in British schools and related policy initiatives on ‘race’, 1962–89

For many writers in the field, the most compelling and plausible interpretations of these changes appear in the work of Street-Porter (1978), Mullard (1982) and Troyna (1982), who draw on analytical tools which are provided by the sociology of race relations. They specify ideological and policy approaches in terms of assimilation, integration and cultural pluralism. These phases are periodized from the early 1960s through to the mid- 1980s, although they are intended neither to imply a neat and regular progression nor to denote practices at the chalk face’. Their intention is to characterize prevailing ideologies as they are reflected in the rhetoric and policy prescriptions at national and local government level. Each ideological concept embodies a specific ‘racial form of education’ and, according to some writers (e.g. Jeffcoate 1984), denotes particular perceptions and conceptions of the relationship between black pupils and the state. This was not the view of Mullard or Troyna, however. They argued that the move towards cultural pluralist models of education did not constitute a significant departure from the assumptions and principles which underpinned assimilationist conceptions. That is to say, multicultural education, although representing a more liberal variant of the assimilationist model, continued to draw its inspiration and rationale from white, middle-class, professional understandings of how the educational system might best respond to the perceived ‘needs’ and ‘i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series editor’s preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Anti-racist education: a loony tune?

- 2. Who gets what?

- 3. Racist understanding and understanding racism

- 4. The Education Reform Act 1988: to free or not to free?

- 5. The ‘entitlement curriculum’?

- 6. Anti-racism in the new ERA

- References

- Index