![]()

1 Introduction

Natural Resource, Conflict, and Sustainable Development in the Niger Delta

Ibaba Samuel Ibaba, Okechukwu Ukaga and Ukoha O. Ukiwo

Sustainable development of the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria is vital not only to the stability and prosperity of Nigeria, but also to global energy security. However, the Niger Delta has in the past two decades experienced protracted violent conflicts. At the roots of these violent conflicts are the genuine quest of the people for sustainable development that is based on social justice, equity, fairness, and environmental protection. Although richly endowed, the region is hopelessly poor. This paradox of poverty in the midst of plenty has been attributed to a myriad of fractors ranging from Nigeria’s centralized federalism, to ethno-regional domination, corruption, poor governance, and oil-related environmental degradation.

Natural resources can (and often do) play cataclysmic roles in the development of countries. In Nigeria, the discovery of oil in commercial quantity in 1958 marked a turning point in the nation’s economy. The country moved away from agriculture, which hitherto provided the revenue base, and to dependency mainly on oil for revenue and foreign exchange (Usman 2008). Notably, oil and gas contribute 40 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 90 percent of total earnings, and 87 percent of gross national income (Akinola 2010). The country earned $500 billion from oil between 1960 and 2006 (Nafziger 2008). Other estimates indicate that the country also generates $4 billion annually from the export of natural gas (Obi 2009). Since 2000, with the increase from three percent to 13 percent of the share of oil revenue that goes to the relevant state, the Niger Delta region has witnessed huge revenue inflows. In 2008, for instance, six Niger states (Akwa-Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, and Rivers States) received the sum of $7.1 billion out of $16.5 billion allocated to the thirty-six states of the federation1). Despite these huge revenues generated by oil and gas, for the entire country in general and state governments in the region, the Niger Delta, which hosts the oil and gas industry, remains one of the least developed parts in the country (Obi 2010).

The concern for the poor state of development in the region dates back to the colonial period when Niger Deltans, along with other ethnic minorities in the country, expressed fear of domination and development neglect. The colonial government responded by setting up the Willinks Commission in 1957 to determine the veracity of these fears and to proffer solutions. Although the commission acknowledged the validity of the concerns, it failed to agree that state creation, a major demand of the people, was the solution. Instead, it recommended the declaration of the region as an area for special development attention, and recommended the establishment of a special agency to facilitate its development. The commission recognized democratic governance as the only guarantee of the rights of minorities, and predicated its recommendations on the practice of democratic governance in postcolonial Nigeria (Willinks Commission Report 1958).

In 1966, late Major Isaac Adaka Boro, an Ijaw, led the Niger Delta Volunteer Service (NDVS) to declare a Niger Delta Republic. While the goal of becoming a separate country was not achieved, this effort once again highlighted the regions concerns. Development neglect, despite the region’s vast resource potentials, was cited as the justification for the rebellion (Tebekaemi 1982). Later in the early 1970s, oil-producing communities (OPCs) in the region began agitations against the transnational oil companies (TOCs) engaged in oil production in the Niger Delta. The Nigerian oil industry is dominated by TOCs. The most notable is the Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC), which operates a joint venture with the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), and produces about half of the country’s oil. The dominance of TOCs in the Nigerian oil industry, and the fact that Nigerian oil is a significant source of oil for the United States and other countries in Europe and Africa, explains the globalization of the Niger Delta question and the complex dynamics associated with it.

The concerns that resulted in agitations by OPCs pertained mainly to the payment of inadequate compensation for properties destroyed by oil production activities, the destruction of livelihoods without the provision of viable alternatives, and the environmental destruction caused by oil spills and gas flare. The OPCs demanded the payment of adequate compensation for their destroyed properties, basic social amenities such as water and health facilities, environmental protection, employment opportunities, and the award of contracts to indigenes (Okoko 1998). The TOCs responded with community-development support by providing boreholes to supply potable water, school buildings, health centers/cottage hospitals, scholarships, among other things. But the conflicts did not abate, as these provisions made very little impact on the quality of life. OPCs linked protests to the provision of such development support and thus continued to agitate for more, while the TOCs could not respond adequately to the demands for adequate compensation, citing state legislations that had fixed the compensation rates without negotiation or recourse to existing realities (Ibaba 2008). The engagement tactics of the OPCs, which included blockade of oil production facilities such as roads, rig sites, and flow stations, soon became a major concern to the TOCs who lost man hours and missed production targets. The TOCs thus called in security operatives to either quell community protests or protect their facilities.

The repressive tactics of the security operatives—who attacked, injured, and killed people and destroyed property—turned the hitherto peaceful protests violent. A classic example is the case of Umuechem community, where a peaceful protest against the SPDC was met with force by the anti-riot police who killed twenty persons and destroyed 495 houses with hand grenades. Significantly, the protesters’ main complaint was the pollution of their river and source of water, destruction of farmlands, and disruption of normal economic activities by the SPDC oil production (Alapiki 2001). State repression set the stage for the emergence of pan-ethnic and civil society organizations that mobilized the people against the TOCs and the Nigerian government. Organizations such as the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), Movement for the Survival of the Izon Ethnic Nationality in the Delta (MOSIEND), Ijaw National Congress (INC), among others, embarked on mobilization and peaceful protests, demanding development attention as well as an end to oil-induced environmental degradation. MOSOP, the forbearer of these organizations, proclaimed the Ogoni Bill of Rights, a charter of demands on the TOCs and the Nigerian government in 1990, and pursued it vigorously. But the Nigerian government responded with violence, which culminated in the hanging of MOSOP leader Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight of his compatriots following a widely condemned trial and conviction in 1995.

The repression of the Ogoni struggle and the militarization of the region set the stage for violent mobilization against the Nigerian State and the TOCs. Groups such as the Niger Delta People Volunteer Force (NDVF), Niger Delta Vigilante (NDV), and others began to engage security operatives in armed confrontation. The Ijaw Youths Council (IYC), the umbrella body of Ijaw youth, met in Kaima, Bayelsa State, in December 1998 and proclaimed the Kaima Declaration. Among others, the Kaima Declaration demanded the withdrawal of the Nigerian military from the Niger Delta, and the cessation of oil production activities by TOCs, whom they gave an ultimatum to leave the region. The resolution also claimed ownership of all lands and resources in Ijaw land, ceased to recognize all state legislations on the oil industry, and called for the convoking of a sovereign national conference to renegotiate the existence of the Nigerian State (Kaima Declaration 1998). The Kaima Declaration, which closely followed the resolutions of the First Urhobo Economic Summit held in November 1998, was copied by other ethnic groups, which proclaimed their own chatter of demands such as the Warri Accord (1999), the Aklaka Declaration (1999), and the Bill of Rights of the Oron People (1999). The common elements found in all of these demands are self-determination, resource ownership/control, and the convoking of a sovereign national conference.

However, it was youth from the Ijaw ethnic group that led the armed struggle that later turned into insurgency in 2005 (Watts 2007). Ijaw resistance in the Niger Delta is historic, and this latest phase can be located in that historic context. King William Koko of Nembe led a rebellion against the British from 1894 to 1895, over attempts by the latter, represented by the Royal Niger Company, to preclude the Nembe from the palm oil trade that was very lucrative then (UNDP 2006). Ijaw youth were also inspired by Major Adaka Boro, who led the 1966 rebellion to declare the Niger Delta Republic. It is noteworthy that his hometown was chosen for the all Ijaw youth conference that resulted in the Kaima Declaration. The Ijaw role in the counterattacks on security operatives resulted in reprisal attacks on Ijaw communities by Nigerian security forces. Examples include Odi in 1999, Okerenkoko in 2006, Gbaramatu in 2009, and Ayakoromo in 2010. These attacks also led to the proliferation of militia groups, which later formed the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), which coordinated activities of the militia movement and engaged the military directly in armed combats.

MEND’s engagement tactics were mainly attacks on oil infrastructure and kidnapping (hostage taking) of TOCs’ foreign workers. Between 2006 and 2008, it carried out 66 attacks, leading to 317 deaths, 30 injured persons, and 113 victims of kidnapping (NDTCR 2008: 116–119). These attacks disrupted oil production and reduced oil production and exports (Obi 2010; Joab-Peterside 2010), forcing the Nigerian government to proclaim amnesty for militia combatants. The Amnesty Program offered forgiveness to combatants in return for the renunciation of militancy, arms surrender, reintegration, and provision of alternative source of livelihood (Adeyemi-Suenu and Inokoba 2010). The program ended violence as envisaged by the Nigerian government; attacks on oil infrastructure and oil workers are almost non-existent, and oil production has risen to 2.3 million barrels per day (Joab-Peterside 2010). However, there is the possibility of violence recurring if the Amnesty Program fails to address the fundamental issues that caused the violence.

NIGER DELTA: CHALLENGES TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

The Niger Delta is rich in numerous natural resources that endow it with great potentials for sustainable development. But this has been strained by factors that include governance deficits, resource-extraction-induced environmental degradation, and violence.

GOVERNANCE DEFICITS

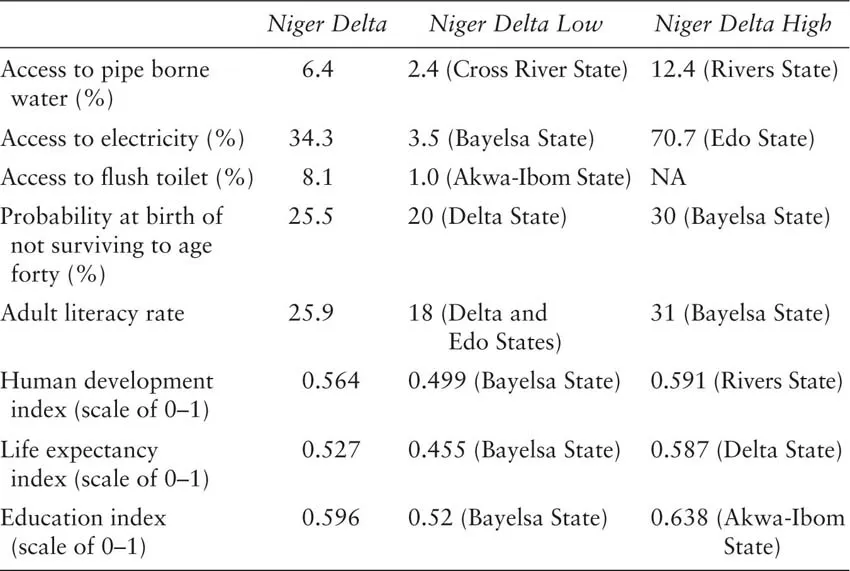

The Niger Delta is a strange paradox. Despite its vast natural resources, including oil and gas, the region ranks low in several indicators of development. This strange paradox of poverty and suffering in a region endowed with so much wealth in form of natural resources illustrates both the symptom and effect of governance deficit. For example, Table 1.1 provides information on quality of life indicators and shows how huge oil and gas revenues have barely touched the lives of majority of the citizens.

Table 1.1 Quality of Life Indicators in the Niger Delta: 2006 Only

Source: Adapted from Ibeanu (2008: 214).

Although current data on basic amenities is not readily available, the figures provided by the 2006 UNDP Niger Delta Human Development Report are instructive. The report shows, for instance, that one primary school served a population of 3,700 or an area of 14 square kilometers, while a secondary serviced a population of 14,679 or an area of 55 square kilometers. For primary health care, the facility population ratio was discovered to be one facility for every 9,805 people, and one secondary health facility for a population of 131,174. The same report indicated that the pipe-borne water provided an infinitesimal source of water, representing only 7.37 percent in Akwa-Ibom State, 7.49 percent in Bayelsa State, 2.43 percent in Cross River State, 2.89 percent in Delta State, 9.70 percent in Edo State, and 12.42 percent in Rivers State.

The dominant view blames governance deficits on the ethnicized character of politics in Nigeria, the abnormal federal system, and the politics of oil wealth distribution. The point is that politics in Nigeria is used to pursue individual and ethnic group interest, and thus, when a particular ethnic group is in power, it allocates state resources to benefit its people and denies other groups a fair share of such resources. In the case of the Niger Delta, the argument is that because it is inhabited by minority ethnic groups, the Nigerian State, which until 2010 was headed by persons from the majority Hausa-Fulani, Igbo, and Yoruba ethnic groups, neglected and deprived the area of development funds and attention, despite its huge contributions to the national treasury. The changes in the revenue allocation formula, which coincided with the emergence of oil as the mainstay of the national economy, is usually cited to vindicate this point. At independence in 1960 and until 1970, derivation2 was a major component of revenue allocation in Nigeria. Within this period, which saw the country depend on agricultural products produced in the home lands of the majority groups, the share of derivation in revenue allocation was 50 percent. But beginning from 1970, when oil displaced agriculture as the basis of the national economy, derivation was reduced first to 45 percent, and later to as low as 1.5 percent in 1981 (Mbanefoh and Egwaikhide 1998; Jega 2007; Idemudia 2009). This is seen as a deliberate ploy to deny the region of development funds. The country’s federal system, characterized by centralization of powers and resources, intersegmental imbalance, and the privatization/personalization of the Nigerian State, is blamed for creating the conditions that supports ethnicity-based political domination3 (Naanen 1995; Okoko, Nna, and Ibaba 2006).

The second-most prominent explanation of the lack of development in the Niger Delta is the nonchalant attitude of TOCs toward corporate social responsibility, exacerbated by the state legislations on the oil industry that has alienated the people from the oil wealth and their environment. Oil industry laws such as the Petroleum Act of 1969, the Land Use act of 1978, and the Oil Pipelines Act of 1956 are highlighted as instruments of disempowerment that have created conditions for underdevelopment (Nna 2001; Idemudia 2010).

But Ikelegbe (2011) has noted correctly that these explanations locate the causal factors of the Niger Delta crisis in externalities by blaming the federal government and the TOCs, and neglects the governance deficits in the region that is part of the fundamentals that underlie its underdevelopment. This view links governance deficits to the political elite and ruling class at the communal, ethnic, state, and regional levels in the Niger Delta, characterized by selfishness, decadence, corruption, ineptitude, and arrogance, which has resulted in the lack of accountability, transparency, and openness in resource use and management. The high-profile corruption cases involving some past governors of the region, who were prosecuted by the Nigerian anti-graft agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), vindicates this point. There are two classic examples. First was the arrest and conviction of Chief D. S. P. Alamieyeseigha, former governor of Bayelsa State, for corrupt practices involving the diversion of public funds to personal use. This was f...