![]()

Chapter 1

The meaning of politics

This book is not mainly about party politics and the curriculum, but about the question ‘who controls the curriculum of secondary schools?’ The answer is not a simple one, and the question itself is of fairly recent origin, only becoming important when the curriculum began to be called into question. When there was no controversy about the content of the curriculum, there was no argument about its control. When the curriculum becomes controversial, however, it is essentially a political controversy. There are two interrelated problems: the distribution of knowledge in society; and the decision-making involved.

If we take 1944 as a crucial date in the development of secondary education, it would be true to say that the following ten years or so were dominated by the debate about the tripartite system: should there be separate schools for different kinds of ability or comprehensive schools catering for all children? By the late 1950s that battle was largely over, and for about the next ten years the discussion shifted to questions of grouping and school organisation: should comprehensive schools be divided vertically into houses or horizontally into year groups? Should we have streaming, or setting, or banding, or mixed ability groups?1 By 1965 these questions about structure had developed, to some extent, into questions about the content of the curriculum, partly stimulated by the work of the Schools Council.2 At the same time some educationists began asking the more fundamental question ‘What is the point of a common school unless we have a common curriculum which transmits a common culture?’

By the mid-1960s it was also becoming clear that the period of consensus in education since 1944 had obscured a number of fundamental ideological problems about the nature of education. From then on disputes often centred on the question of ‘the comprehensive school’ but they went much deeper than a difference of opinion about whether grammar schools should survive or not. The Black Papers3 (from 1969 onwards) helped to illustrate at least two of these areas of conflict: whether schools should concentrate on an elite few or on the majority; whether the purpose of education was to develop individuals or to socialise children to fit in to the existing social structure.

On the first of those issues the Labour Party has always been divided, and that is one reason for deciding to avoid identifying party politics with the politics of the curriculum: it is much more complicated than a simple left versus right confrontation. Within the Labour Party, many individuals valued grammar schools because they had helped bright working-class youngsters to climb the ladder of opportunity: for this group of politicians (and many others) comprehensive schools would only be ‘successful’ if they enabled more working-class pupils to climb even higher up the ladder and away from their own social origins. For such Labour Party ‘elitists’ an important feature of comprehensive schools would be selection and streaming so that the ‘able’ would be helped on their journey upwards and not held back by those less gifted.

This debate goes back a long way in labour history. As early as 1897 the Trades Union Congress had demanded a policy of secondary education for all, condemning the segregation of elementary and secondary-school pupils. At that stage they were firmly against the elitist basis of the grammar-school curriculum. But the Fabian Society, and in particular Sidney and Beatrice Webb, had pursued a policy very much in the liberal tradition of utilitarian philosophy, justifying selection on grounds of economic and social efficiency.4 So there is a fundamental difference in outlook, even between those in the same political party (the Labour Party); it may be convenient to label one group egalitarians and the other elitists, although this terminology is not entirely satisfactory. Egalitarians want a worthwhile curriculum for all children; elitists are concerned to select the brightest for a superior, academic curriculum.

The question ‘who shall be educated?’ is clearly related to the question of ‘what are schools for?’ – is it to make life more worthwhile for all individuals, or to make society work more efficiently? Sidney and Beatrice Webb and many early Fabians belonged to the philosophical tradition which emphasised education as a means of making society a better place in the sense of a more efficient organisation. Sidney Webb's book London Education (1904) described the kind of ‘capacity catching’ machinery of scholarships which would ensure efficient leadership for society at home and in the British Empire. Webb was totally opposed to the idea of a common school with a common curriculum, and accepted the Morant policy (1902-4) of sharp differentiation between elementary and secondary curricula. In fact Sidney Webb's views were so similar to the Conservative policy on secondary education at that time that in January 1901 Sir John Gorst, the Conservative education minister, distributed proof copies of Webb's Fabian Manifesto The Educational Muddle and the Way Out in support of the Conservative policy of clearly separating elementary and secondary schools, but providing a scholarship ladder which would enable a few very bright working-class children to pass from elementary schools into the secondary schools.5 In the House of Commons the two members sponsored by the Labour Representative Committee (the precursor of the Parliamentary Labour Party) opposed the 1902 Education Bill; at that time the majority of the Labour Movement was on their side, but an influential part of the Fabian Society had firmly established a non-socialist tradition which the Labour Party was later to inherit and to preserve.

The Labour Movement as a whole tended to see the 1902 Act as a piece of class legislation. In their social and educational views the Labour Movement covered a very wide range: ‘Elitism and egalitarianism with Webb at one end, Thorne and Hobson at the other, and the ILP somewhere in the middle, provided the limits within which Labourism was set rather than the framework on which it was built’ (Barker, 1972, p. 18).6 The dispute was, of course, not simply about the structure of education into secondary and elementary: the content of the curriculum was at stake as well.

A more recent version of the dispute between egalitarians and elitists centres on the word ‘meritocratic’. In 1958 Michael Young published The Rise of the Meritocracy, which should have succeeded in demolishing the meritocratic point of view. The book was described as a fable narrating the development of a meritocratic society some time in the future. A society (England in the future) is described where ‘I.Q. plus effort = merit’.7 This was a society where the most intelligent had to be detected at an early age and given the opportunity to benefit from an intensive educational programme. If they responded with appropriate effort they were ultimately rewarded by being allotted a position in life in accordance with their carefully calculated ‘merit’. It was, needless to say, described as a nightmare world where efficiency took precedence over humanity, and where those who lacked measured ability were destined to a carefully planned inferior life. Implicitly the question was asked (which had been ignored by many who considered themselves to be concerned with social justice): if it is unfair for children to have a better education because they happen to be born rich, is it any less unfair for children to have preferential treatment because they happen to be born with a high IQ?

One of the messages in Young's book was that the meritocratic position rests on an inadequate view of democracy: true democracy in a free society should include a better quality of life for all, and the vast majority of the population should have access to worthwhile educational experiences, not just an elite few – whether they are a social or an intellectual elite.

So one ‘political’ dispute about the curriculum is whether an educational programme should be planned for the most able pupils which is quite different in content and form from the curriculum designed for the majority. A related (but distinct) question is whether there should be a curriculum planned for all pupils which has some common elements.

If it is decided to give a superior curriculum to the elite and an inferior curriculum to the majority, then two kinds of decisions must be made. First, it is necessary to decide who goes into which category; second, it is necessary to decide what kind of curriculum would be suitable for those two groups. Both decisions are essentially political: the first decision exerts control over who is to have access to the power bestowed by certain kinds of knowledge; the second involves a judgment about the relative statuses of kinds of knowledge – a judgment which, of course, tends to confirm those statuses.

If a preference is expressed for concentrating on providing a common curriculum, then the first decision (that is allocation to two different levels of curricula) is avoided, but not the second – the determination of what will go into a common curriculum. But perhaps the second question is not as difficult as it seems. The argument in favour of a common curriculum is usually made along one or more of the following three lines:

1 Comprehensive schools were introduced partly to equalise opportunities, that is, to give groups such as working-class children and girls of all classes a better education. But if you divide children into categories at an early stage of their education (academic and non-academic; grammar and modern) and give them different curricula, then you effectively prevent those following a non-academic curriculum ever becoming ‘academic’: they cannot ‘catch up’ because they are effectively running in a separate race. The benefits of comprehensive schools can be nullified by curricular differentiation at too early a stage.

2 A second argument in favour of comprehensive schools was that separate schools tended to divide pupils socially and culturally as well as intellectually. Common schools help to ‘unify society’; but this social and cultural unification would only take place if there were some kind of genuine common experience – a common curriculum – within the common schools. Otherwise, as Julienne Ford pointed out (1969), the divided system was simply perpetuated under one roof by means of ‘streams’ which possessed quite different ‘cultures’. It might be argued that television has done more for cultural unification than education, but that does not negate the argument that schools have a part to play in unifying society.

3 A third argument for a common curriculum is not necessarily connected with comprehensive schools at all. It suggests that if the state makes education compulsory for the 5-16 age group, then (because we value freedom highly in our society) it is the duty of the state to specify as far as possible the advantages to be gained by the child to compensate for eleven years’ loss of freedom. At first these advantages tended to be taken for granted – it was simply assumed that education was ‘a good thing’; but when education as an institution comes under attack then that assumption can no longer be taken for granted, and has to be justified in rational terms. Such a justification is difficult, if not impossible, without an explicit statement about the benefits bestowed by education in terms of curriculum content. This should be based upon a cultural analysis of the knowledge and skills which young people need in our society and the kinds of experiences that can be regarded as sufficiently ‘worthwhile’ to be made available for all.

If it is argued that education is not mainly about making society efficient, but is more concerned with giving as many people as possible access to a worthwhile life, then the problem of curriculum planning is not seen as the need to supply trained manpower for industry but as making a selection of the most important aspects of culture for transmission to the next generation. Then the crucial cultural question is ‘what is worthwhile?’, and the crucial political question is ‘who makes the selection?’

Some recent sociologists specialising in the sociology of knowledge would have us believe that control of the curriculum is simply a question of bourgeois hegemony.8 They assume that in a capitalist society the whole of the cultural superstructure, including education, is a reflection of the values of the dominant group – i.e. the bourgeoisie or the capitalist ruling class. For this group of writers education is assumed to be a totally socialising influence. But I am suggesting that the question of the control of education and the content of education is much more complicated than that especially in a pluralist society. As I have argued that point in detail elsewhere (Lawton, 1975), in this book I would prefer to concentrate on the task of analysing who makes the decisions in our society about the organisation, the content and the planning of the curriculum. As well as questions about ‘who?’, there are related questions about ‘how?’ and ‘why?’

One familiar answer to the question of ‘who controls the curriculum?’ is that in the UK, unlike any other country, teachers decide on their own curriculum – teachers are free to make their own selection. Teachers in England and Wales are certainly more free in this respect than in most other systems, but it would be a mistake to over-simplify the situation by exaggerating teachers’ autonomy (as we shall see in Chapter 2). Secondary teachers’ freedom to select their own curriculum content has legally existed only since 1945, and is today increasingly under attack.

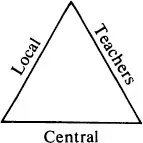

Another familiar view is that in England and Wales we have a national system of education which is locally administered, leaving the implementation in the hands of teachers themselves. This may be seen in terms of a triangle of power: the central authority (DES), the local authority (LEAs) and the teachers.

Figure 1.1

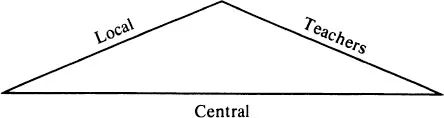

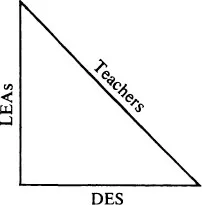

As we shall see in Chapter 2, there is an important ambiguity in this ‘triangle’. The teachers’ can refer either to the organised bodies of teachers (teachers’ unions and professional associations) or to the fact that whatever the central or local authority may prescribe, the interpretation of the curriculum must always be in the hands of teachers.9 If power is measured in terms of the length of each side of the triangle, it is clearly possible to have triangles of different shapes: in other words it would be a mistake to assume either that the triangle is equilateral or that angles do not change from time to time, especially if we are concerned with the control of the curriculum.

Figure 1.2 Nineteenth century?

Figure 1.3 Post-1945?

It may be useful to begin with a description of the formal position of each of these three ‘partners’ in relation to the secondary curriculum:

1 The DES now has little formal control over the curriculum. The word curriculum does not appear in the 1944 Education Act (which is still the major piece of legislation governing education); and no curriculum content is legally specified in secondary schools apart from religious instruction. But that does not necessarily mean that there could be no central influence or even control under the 1944 A...