![]()

Chapter 1

Educational Facts and Intellectual Interpretations

This chapter begins with an inventory of some of the most evident features of the current difficulties or ‘crisis’ in state-run, mass-based school systems and in the relations between this form of education and its societal context in the major industrial market societies.1 Then an attempt is made to characterize, in very general terms, the different types of intellectual interpretations of education/society relations that have been developed in the post-World War II period and to suggest the association of such respective interpretations with the changing historical context and the divergent social alignments of educational researchers themselves. Next, the basic elements of the historical materialist approach that will be used in this book to interpret education/society relations in advanced capitalism are presented.2 In the final section, this historical materialist approach is applied to begin to develop a critical analysis of the current educational crisis.

The Current Educational Crisis

School is not dead in advanced capitalist societies, but it is certainly not very healthy. Over the past generation, the incidence of such individual student acts as classroom violence, truancy, vandalism and dropping out has generally increased in the state-run, mass-based school systems of all western industrial countries. More collective expressions of unrest with existing school provisions and related social institutions have frequently appeared in such forms as rebellious youth cultures, student political movements, increasingly militant teachers’ organizations often bonding together with other state workers and clients to fight budget cuts, and parent and other interest group movements pressing for various types of reorientation of the schooling process. Mass opinion polls document a growing general sentiment of dissatisfaction with the schools. Educational debate in both Western Europe and North America has become increasingly focused on basic organizational concerns. Among the fundamental issues on which there is now visible, persistent dispute in most countries are the following: whether control of the school system should be more centralized or more localized; whether the learning process should emphasize ‘the basics’, rigid discipline and universal standards, or curricula built from children’s actual experiences and cultural differences; whether equality of educational opportunity should be more fully provided through affirmative action measures for disadvantaged groups or, conversely, whether merit criteria should be more exclusively emphasized in the light of growing economic demand for highly trained scientific and technical personnel; and whether specific job skills or more general adaptive skills should be emphasized in linking school programmes more effectively with the world of work. While the particular character of existing school provisions and the growing patterns of criticism may differ substantially, in each of these countries a number of institutional features of schooling that were previously taken for granted by all are now being questioned by many. Government commissions to propose the institutional reorganization of various levels of the school system have recently been established within most countries. In short, we are in the midst of an ‘educational crisis’.

In many respects, such a situation is not unique. Even the most cursory glance at the history of public schooling since its inception, less than two centuries ago, reveals recurrent periods of intense criticism of the adequacy of established forms of schooling to meet evident social and economic needs. Revisionist educational historians have now extensively re-examined some of the major nineteenth century periods of educational conflict and documented the often divergent interests of leading business and professional groups involved in criticizing and transforming the dominant institutional forms of state schooling. Within the twentieth century, such conflicts have been somewhat less evident and more muted, as they have been largely encapsulated within a single, taken-for-granted general form of schooling. As the leading revisionist, Michael Katz, noted for the United States that by 1880:

American education had acquired its fundamental structural characteristics, they have not altered since. Public education was universal, tax-supported, free, compulsory, bureaucratically arranged, class based, and racist.3

Moreover, within this general form of schooling a number of more specific organizational features have been quite fully institutionalized over the past hundred years with little serious dispute. These include: full-time attendance; age grouping; an increasing reliance on teacher-dominated classroom instruction of age groups, with declining assistance by home instruction or student monitors; the graded curriculum; extensive and standardized supervision of students; expansion of the size of schools, school systems and administrative hierarchies; and the extension of the school day and of the extra-curricular responsibilities assumed by school staffs.4

Nevertheless, periodic educational crises have remained discernible. Marxist scholars, in particular, have begun to analyze systematic connections between economic crises and educational reform movements in this century. The most seminal work, by Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, focuses on the progressive education movement at the turn of the century and the current period of ‘educational change and ferment’ in the US, as well as the nineteenth century era of the common school reform. They conclude that:

... the main periods of educational reform coincided with, or immediately followed, periods of deep social unrest and political conflict. The major reform periods have been preceded by the opening up of a significant divergence between the ever-changing social organization of production and the structure of education … The three turning points in US educational history which we have identified all correspond to particularly intense periods of struggle around the expansion of capitalist production relations.5

While subsequent critics have justifiably scored the simplistic formulation of Bowles and Gintis’ ‘Correspondence principle’, their major empirical conclusions remain largely unassailed.6 Indeed, at least in the most recent periods of economic crisis, some of these connections have become clear enough to many educators themselves. As Merle Curti observed in 1935, in his historical review of the social ideas of leading American educators:

The depression of 1929 and subsequent years … like the World War, made educators of every shade of opinion more socially conscious and more willing to assume new responsibilities for building a better and more truly democratic order. The depressions of 1837 and 1857 had stimulated some educators to assume special responsibility for preventing such catastrophes in the future, but the debacle of 1929 had more far reaching effects. The economic crisis, as Judd reminded his educational colleagues, ‘has made us all aware in a new and vivid way that schools are a part of the general social order and that the curriculums of schools and their methods of dealing with pupils are largely determined by the conditions of life outside the schools’.7

A similar awareness has re-emerged in the current period. As the Swedish comparative researcher, Torsten Husen, puts it:

The most evident symptom of changed attitudes towards education is the wave of criticism from both left and right that swept many countries in the late 1960s. The former consensus about the benefits of traditional schooling and the conviction that education always represented an intrinsic good were gone. So was the belief that education was the main instrument for bringing about a better society ... A by-product of the debate was the growing awareness that the schools of a given country operate within a given social and economic framework, whereas prior to the 1960s school problems were often conceived of as purely pedagogical ones that emerged in a socio-economic vacuum. This widening of the perspective has been beneficial to the debate, because it has led to the realization that problems besetting the educational system are in the last analysis social problems which cannot be solved simply by taking action only within the walls of the school.8

Typically, it has been some time after the onset of such economic crises that educational leaders have been moved to reassess established educational practices. Curti further observed that:

... it was only in the later stages of the depression, when business support was increasingly withdrawn from the schools, that educators were thoroughly aroused regarding the educational, social and economic crisis: and that even then their attitude and program, with some exceptions, was more conservative than that which the Federal Council of Churches took in September, 1931.9

Similarly today, it has been some years after the onset of the current period of economic stagnation and fiscal crisis, and in the face of substantial education budget cuts, that educational leaders once again have become concerned enough about such symptoms to consider seriously any basic reforms of established organizational forms of schooling.

However, the current ‘educational crisis’ is also quite distinct in several respects. It is much more extensive and more sustained than previous periods of educational conflict. In reviewing the history of conflict in the British educational system, Tapper and Salter conclude that:

Although past educational issues have resulted in bitter controversies … they appear to have been successfully contained in terms of their duration, the range of the interested parties involved, the confining of the debate to established elites, and the limitation of its wider societal impact. This is in direct contrast to the present situation for the conflict is continuous, it is not confined to the elite levels of a few interested parties, and the issues being raised have direct implications for the overall character of the society.10

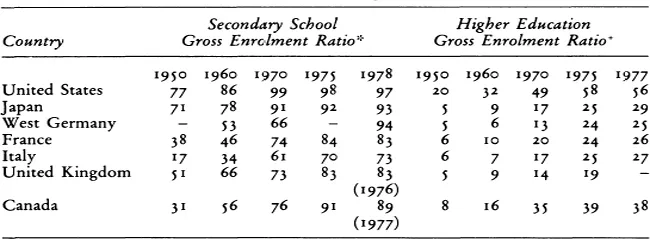

While Tapper and Salter may have seriously underestimated the role of subordinate groups in stimulating earlier educational reforms,11 there can be little doubt that the current ‘debate’ involves far more active participants than any previous crisis period. In contrast to the 1930s, the vast majority of the ‘eligible’ age group are now enrolled in secondary schools, higher education has expanded very rapidly to include at least a quarter of the 20 to 24 age group in most advanced capitalist societies, and the majority of the older population have attained some measure of secondary schooling and come to regard continuing access to advanced schooling as an entitlement for their children. Post-World War II trends in participation rates are shown in table 1. Clearly, a far greater proportion of the population stands to be directly affected by persistent cutbacks and reorganization initiatives than in prior crises.

Table 1 Post-War Trends in Educational Participation

Indeed, whereas in previous economic crises the secondary schools served only a minority of those eligible and higher education remained an elite preserve, the schools in the post-War period have become the central institution for socializing and selecting virtually all the young people of advanced capitalist societies into their adult pursuits. To reorient such a pervasive institution in response to economic crisis has become an extraordinarily difficult and delicate matter. In the wake of the post-War economic expansion, public expenditures on schooling in many of the industrial market economies of Western Europe and North America were permitted to increase their share of the GNP from two to three percent in the 1950s to six to eight percent in the late 1960s, including massive capital outlays to build new universities, colleges and urban schools. Educational expenditures grew much faster than economic productivity and considerably faster than total goverment revenues. The educational infrastructure established in the 1960s facilitated the unprecedented growth of higher education enrolments which continued throughout the early 1970s. With the economic stagnation of the 1970s, the increased productivity and enhanced life chances long associated with advanced schooling were gradually perceived to be false promises as more and more educated youths faced unemployment and extended underemployment. More generally, as growing numbers not only heard the many promises but experienced the reality of advanced schooling, various inadequacies and contradictions became widely evident. The situation had reached the point that, by the early 1970s, radical criticisms directed at the false identity between schooling and education as a generic human activity, and at the dominant general form of schooling, as well as proposals to abolish schools and create alternative forms of education for young people, began to be listened to seriously for the first time in over a century.12 But by the early 1980s, the deschoolers have been largely forgotten. In a context in which the most palpable alter...