eBook - ePub

Beyond the Global Crisis

Structural Adjustments and Regional Integration in Europe and Latin America

This is a test

- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Beyond the Global Crisis

Structural Adjustments and Regional Integration in Europe and Latin America

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book aims at offering a comparative, multi-perspective analysis of the different, at times parallel, at times with varying degrees of interdependence, macroeconomic and structural adjustments in the two continents against the backdrop of important processes of regional integration. Its reading offers a multifaceted appreciation of the reality emerging from the mixing up of longer run tendencies deepened by the brute force of the financial and then industrial crisis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Beyond the Global Crisis by Lionello Punzo,Carmem Feijo,Martin Puchet Anyul in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The two continents’ macroeconomic scenarios

1 Growth under strain in the European Union

A long-run perspective

1.1 Introduction: the determinants of long-run growth in theoretical models

The formalization of economic growth theory was started by the neoclassical model set up by Solow (1956), where the accumulation of capital and labour eventually ends in the stationary state as the saving rate can no longer sustain the expansion of the economy. Given the hypothesis of constant returns to scale, the growth accounting of the income share accruing to each factor (the output elasticity of the input multiplied by its accumulation) adds up to one. Since the growth accounting of real economies exhibits a “residual” which is neither reflected by the contribution of capital nor of labour input, this further output formation is ascribed to efficiency in the combination of factors of production, namely total factor productivity (hereafter, TFP). The Solovian view of a smooth process of GDP increases has the drawback of considering technical progress, which is the most crucial variable ruling the growth path, as an exogenous variable.

A first attempt to bring technical progress into the picture consisted in considering labour in units of efficiency, so to prevent diminishing returns of the labour input and open the growth model to the possibility for per capita income to follow a steady expansionary path (Mankiw et al., 1992). The subsequent generation of “endogenous growth” models (Romer, 1986, 1990; Aghion and Howitt, 1992) was dedicated to the modelling of increasing returns to scale. The hypothesis of technical progress (the technological coefficient A considered in the production function) growing at the same rate of labour effort allows the capital per unit of labour efficiency (labour in units of effort) to remain constant, and the per capita income to grow without limits. In this perspective, human capital can be analysed not only as a further input to the production process along with physical capital and unskilled labour, but also as the increase in the number of high-education workers, employed as researchers in R&D laboratories, with respect to those employed in the production sites (Aghion and Howitt, 1992). Knowledge then feeds the growth in TFP through the discovery and adaption of new ideas and innovations capable of endogenously propagating capital accumulation. In the words of Gary Becker (2002), “(t)echnology may be the driver of a modern economy, especially of its high-tech sector, but human capital is certainly the fuel”.

Since knowledge and human capital are more important for growth than the accumulation of physical capital, microeconomic foundations modelling the technological frontier have been worked out. Innovations push the leading economies to continuously move the technological frontier forward, thus defeating the Solovian view of a smooth catching-up process by the backward economies.1 Countries closer to the world technology frontier follow an innovation-based strategy characterized by the leading role of science-based companies and by a clever selection of firms and managers. Technologically backward countries instead pursue an investment-based strategy, which relies on capital accumulation through the imitation of innovations and their diffusion in the manufacturing firms (Acemoglu et al., 2006).

A more radical departure from the constant returns to scale paradigm is implied by the increasing returns of the capital and labour inputs stemming from the introduction of imperfect competition markets. The New Economic Geography approach underlines the central role of agglomeration factors (universities, R&D laboratories, etc.) in fostering the territorial concentration of companies attracted by the high level of human capital of workers, researchers and managers (Krugman, 1991). Since technical progress is a not-completely-excludable non-rival public good, the incentive of expected profits is preserved by the appropriability of innovations within networks of firms, through patents and the spreading-over of technical progress by the learning by doing. Hence, production districts exhibit increasing returns to scale, with social returns to investment exceeding private returns to investment (Vandenbussche et al., 2006).

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the per capita income gap of the European Union vis-à-vis the United States (hereafter, US) is scrutinized. Section 3 evaluates economic convergence across the Western and the Central and Eastern European countries. Section 4 examines the evolution of per capita income across the European nations and regions, according to the analytical instruments provided by the theories of endogenous growth. Section 5 concludes.

1.2 Fifty years of economic growth in the European Union and the United States

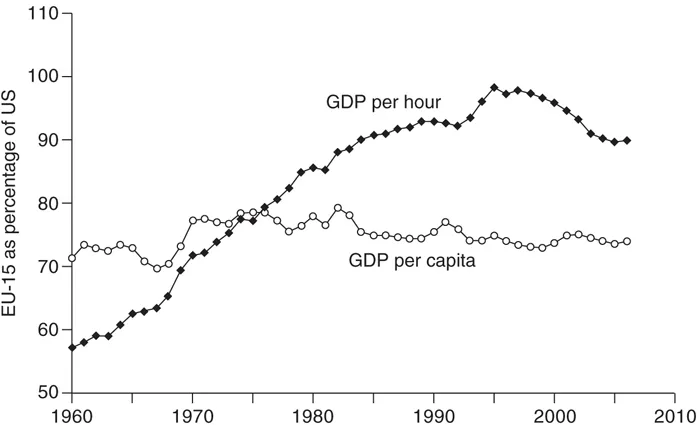

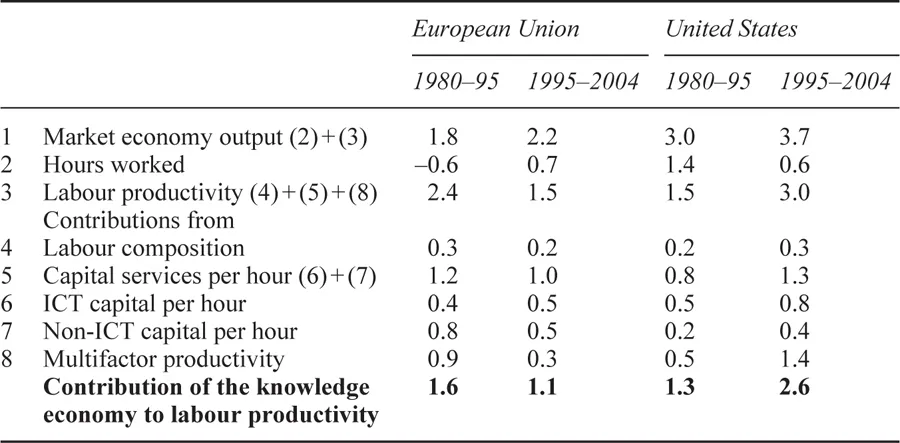

Figure 1.1 clearly portrays the lack of a pattern of catching-up of the European Union vis-à-vis the United States per capita income since 1960.2 Figure 1.1 also shows that the productivity gap between the two narrowed from 25 per cent in 1973 to 2 per cent only in 1995, by virtue of an average annual labour productivity growth in the European Union (2.4 per cent) twice as fast as in the United States (1.2 per cent). The gap then widened again to almost 10 per cent in 2008 (see Table 1.1). An unchanged gap in per capita income in the presence of a narrowing gap in labour productivity till 1995 can be explained by quite different trends in TFP, labour productivity and working hours.3

Figure 1.1 Total economy GDP per hour worked and GDP per capita in EU-15, 1960–2006 (relative to the United States).

(source: The Conference Board and Groningen Growth and Development Centre, Total Economy Database)

Table 1.1 Contributions to growth of real output in the market economy, European Union and the United States, 1980–2004 (annual average growth rates, in percentage points)

Source: EU KLEMS database.

The exceptional growth rates of post-war Europe were due to high investment rates imitating and developing innovations mainly from the US, which rapidly decreased unemployment rates and lifted both productivity and wage levels. The distributive conflict between capital and labour, following the 1973–74 enormous rise in oil price, negatively impinged on investment projects. During the 1975–85 decade of high inflation created by the wage-price spiral, capital intensity increased due to the introduction of labour-saving techniques. During the decade 1985–95, the agreement to abolish competitive devaluations and pursue a process of monetary integration aimed at achieving the “common good” of convergence to low inflation required a switch to anti-inflationary monetary policies. Due to the long period of high real interest rates, firms slowed down the implementation of investment projects, so that the introduction of technical progress in the manufacturing sectors was severely delayed. In the European Union prior to the last two enlargements (hereafter, EU-15) the rate of expansion of output progressively reduced, so that the catching-up process was stuck since the 1990s at around 70 per cent of the US level (see Figure 1.1).

Therefore, the EU-15 does not compare favourably with the United States for the three knowledge economy components summarized in the last row of Table 1.1, respectively expressing high-skill to low-skill workers ratio, investment in ICT and TFP growth.

In the decade 1995–2004, the resurgence of productivity growth in the United States was a combination of high levels of investment in ICT starting from the mid-1990s and of the rapid productivity growth in the market services sector starting during the 2000s. In the EU-15, instead, a much weaker growth in TFP in the whole period 1980–2004, as well as the ICT investments and the ratio of high-skill to low-skill workers exhibiting much lower growth rates than in the US after 1995, make it clear that the higher-than-in-the-US labour productivity growth of the 1980–95 period had not been due to a more educated labour force combined with more innovative physical capital, but to a structurally low participation rate and a declining employment rate.4 In fact, a low growth rate negatively impinged on employment during the two decades in which the European monetary integration was carried out (1979–99). Job creation revived from the mid-1990s onwards – mainly, in Spain and in Italy – because the softening in labour market regulation allowed an increase in temporary contracts. However, growth rates have continued to be unsatisfactory: the unemployment rates were substantial also before the present crisis, and an hourly productivity higher in EU-15 than in the US was almost completely offset by the reduction in the number of hours worked.5

These developments explain why the contribution of capital deepening to labour productivity growth, in particular of information and communications technology per working hour, has been lower in the EU-15 than in the US. The depressing performance of Europe as for TFP growth was the consequence not only of little innovation in sectors specialized in technology, but also of the lack of diffusion of new technologies in the user manufacturing sectors (von Ark et al., 2008). Being short of a significant impact of innovative capital on labour productivity growth, the EU-15 economies are also more vulnerable to negative shocks. In fact, starting from the mid-1990s the impact of technological progress on the TFP in the United States consisted of increases both in labour productivity and in employment. On the contrary, in the EU-15, a negative business cycle causes an enduring decline in labour productivity, as market adjustment through job cuts is prevented by employment protection legislation, and the employment and output recovery after a recession often reflects a lower labour productivity.

The adhesion of the Central and East European countries (hereafter, CEEC) to the EU in 2004 and 2007 has not changed much the overall labour productivity gap between the EU-27 and the US. Labour productivity in the CEEC has been catching up well (so that the real wage increased in the CEEC during the decade 1995–2005 by 3.5 per cent per year, against a meagre 1 per cent in the EU-15), but starting from an initial level lower than in any of the EU-15 countries, in Bulgaria and Romania more than elsewhere. The employment performance is not as satisfactory because labour markets are characterized by a lower average participation rate – around 65 per cent, against 73 per cent for the EU-15 – and a higher structural unemployment ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I. The two continents’ macroeconomic scenarios

- PART II. Sectors, technologies and trade

- PART III. Third millennium industries: Their future in the two continents

- Index