![]()

Chapter 1

Simple Learning

I. P. PAVLOV (1849–1936)

Susan Kenny, aged 9 years, is seated in her classroom listening fairly attentively to her teacher reading R. L. Stevenson’s poem, ‘The Railway Carriage’. Her attention is momentarily distracted by Malcolm Weir who is engaged in drawing a railway engine on the lid of his desk. At this moment Miss Way, the teacher, who is feeling somewhat tired and irritable, asks Susan to explain the last line read. Unfortunately Susan is unable to do this and receives a rather severe reprimand and is singled out for constant reproof for the remainder of the poetry lesson. At the conclusion of the period Susan, usually a happy girl who enjoys most school activities, is heard to remark, ‘Silly old thing, who wants to listen to soppy stuff like that?’

Being a good-natured child she soon recovers her composure and by the end of the afternoon has apparently forgotten the whole incident. Subsequently, however, she has similar experiences in the poetry lessons which she never really enjoys again either with Miss Way or with other teachers. We could say that Susan has been ‘conditioned’ to dislike poetry. The word ‘conditioned’ is frequently used today with rather sinister overtones often associated with political indoctrination.

The word ‘indoctrination’ is deliberately being introduced here since it will possibly cause some slight emotional discord in the reader. Why is this? Perhaps we associate indoctrination with some mysterious treatment which is meted out to political prisoners in different parts of the world. This may seem a long way from 9-year-old Susan Kenny and her poetry lesson. Susan, however, has undergone (in our example) a change of emotional response; and if we consider for a moment we shall probably discover that many of our own emotions are conditioned. Sometimes a certain tune, or a particular voice or picture will cause in us a momentary change in mood. We might find the reason for this too difficult to explain, and Susan Kenny would also probably find it problematic to explain in years to come why she never really enjoyed poetry. If you consider any such feelings which you may have about different school ‘subjects’, you may perhaps be able to explain why you liked history but hated English, or enjoyed chemistry but could never get on with physics.

But what has all this to do with simple learning? Susan Kenny has learnt to dislike poetry; she responds to it in a different way, and there has been a more or less permanent change in her behaviour which may be regarded as a form of learning. It is simple learning and is often associated with the emotional aspects of behaviour of which teachers and teachers in training should be very aware. Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936), the Russian psychologist, first introduced this concept known as classical conditioning in 1909 (1). He was primarily a physiologist and was interested in measuring the flow of saliva in dogs as part of his study of the digestive glands. When food is placed in the mouth of a dog saliva begins to flow, but Pavlov noticed that it also began to flow before the food was actually placed in the dog’s mouth. In fact the dog would salivate at the mere appearance of the attendant bringing the food. This fact intrigued Pavlov and it is an indication of his brilliance that he decided to investigate the strange phenomenon instead of just dismissing it as a triviality.

He designed a basic experiment in which a dog was held in a loose harness set in a sound-proof room. The dog’s parotid gland had previously been exposed on the outside of its cheek in order that the saliva could be collected and measured. By means of remote control Pavlov was able to introduce some meat powder into the animal’s mouth. A metronome was set in motion and at almost the same time, or after a very short interval, the meat powder was introduced into the dog’s mouth. The dog salivated and the amount of salivation was recorded. This process of pairing sound and food was repeated about twenty times. Finally the metronome was started on its own, the dog salivated without any presentation of food, and the salivation was measured.

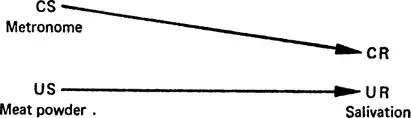

A variety of alternatives were used for the metronome, such as a buzzer, a light or a bell, and similar results were achieved. This, then, was simple learning and the basis of the process was the establishment of an association between the stimulus (S) of the metronome and the response or reflex (R) of the salivation. The dog had learned to respond to the stimulus (S), the sound, with a response (R), the salivation, which was previously associated with the stimulus of the food. Pavlov called the salivation the unconditioned reflex (UR), while the meat powder was known as the unconditioned stimulus (US). The metronome was the conditioned stimulus (CS), and the salivation became the conditioned reflex (CR). This is represented by the diagram shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1

The word ‘association’ has purposely been used because Pavlov’s work is often regarded as an objective demonstration of the idea of associationism which was first introduced by Aristotle as an explanation of learning. A simple example of this would be the fact that if you were to see one of your former teachers you would most likely be reminded of your old school, since in your previous experience the teacher and the school occurred together in place and time. The occurrence of these together is referred to as contiguity, an idea which was developed by a group of British philosophers known as the Empiricists during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Prominent among these were John Locke, David Hume, John and James Mill and Herbert Spencer, who all considered that mental activity was nothing but the association of ideas. An idea included both the emotion experienced and the perception of the object.

Pavlov saw learning as an association between a stimulus (S) and a response (R) which had been paired together. Being essentially a physiologist he expressed his ideas in physiological terms, but his physiology appears somewhat suspect today in the light of modern research. He argued that all behaviour was the result of reflex actions to certain stimuli which could be either external, such as visual, aural and tactile, or internal, that is, changes in body metabolism due to hunger, thirst, fatigue and so on. These internal stimuli are called proprioceptive stimuli. Pavlov, to whom the central nervous system (the brain and the spinal cord) was a kind of telephone switchboard, believed that both the meat powder (US) and the metronome (CS) were represented as separate points in the cortex of the brain. After a time the excitation of the point corresponding to the CS would actuate the point corresponding to the US, and the salivation (CR) would occur. This explanation of the physiological processes in the brain has to some extent been superseded in recent years by a more sophisticated understanding of the central nervous system and the part played by the reticular activating system, the limbic system and the hypothalamus (see Chapter 5). Nevertheless Pavlov has provided a number of concepts vitally concerned with learning. As J. Deese and S. H. Hulse comment,

This basic experiment of Pavlov’s has had an enormous influence upon the psychology of learning, and the terms conditional and unconditioned stimuli and conditioned and unconditioned responses are part of the basic vocabulary of the psychology of learning’ (2; p. 10).

Some of Pavlov’s important findings were as follows:

1. Extinction In the basic experiment the CS (metronome) and the US (meat powder) are closely paired. If after conditioning has been achieved the CS is presented a number of times without the US, the CR (salivation) gradually becomes weaker and finally disappears completely.

2. Spontaneous Recovery If, however, after an appreciable delay the CS is presented again the CR reappears. A direct parallel might be that we often recall events that we had long forgotten when we unexpectedly meet someone we have not seen for years.

3. Generalisation After the CR has been established with the CS, and a new CS similar to the original CS is presented, the same CR occurs. For example, if the CS is the sound of a bell, a similar CR can be obtained by changing the tone, or if it is a light a similar CR can be obtained by varying the intensity of the light. Thus the CR generalises to the change of stimulus. The greater the similarity of the S the greater the response, the less similar the S the weaker the response. This has some important implications for education which will be referred to later on in the chapter entitled ‘Transfer of Learning’.

4. Discrimination Again, it is possible to learn to discriminate between very similar stimuli and to respond to one and not to the other. Pavlov’s dog learnt to respond to a circle but not to an ellipse, and also to discriminate between similar sounds of nearly equal volume. In everyday life we have to learn to discriminate between similar stimuli, otherwise we would be making a number of similar responses to different stimuli. For example, in school we learn to discriminate between the ringing of the school bell for the end of lessons and the ringing of the same bell as a fire warning; and when driving we quickly learn to discriminate between a green and red light.

Pavlov’s work is only very briefly indicated here, but the interested reader will find a much fuller development of it in the books by E. R. Hilgard (3) and W. F. Hill (4). Although, as E. A. Lunzer (5; p. 9) says, ‘Pavlov made no attempt to extend his conception of learning to allow of its implication to teaching’, it might well be considered that the ability to generalise and to discriminate forms the basis of learning and education. A child learning to read is taught to generalise from ‘s-and’ to ‘l-and’ and ‘h-and’, and also to discriminate between such words as ‘there’ and ‘their’. When a child acquires the ability to classify, he generalises dogs, cats, horses, etc., as ‘animals’, and later he learns to discriminate between the different varieties of dogs. As teachers we must be careful to provide children with material containing sufficient common elements so that they may generalise, but we should not confuse them by providing material which is so similar that they experience difficulty in discriminating between common elements.

E. L. THORNDIKE (1874–1949)

Towards the end of the nineteenth century E. L. Thorndike, an American psychologist, was also interested in the scientific study of learning (6). Thorndike agreed with Pavlov that behaviour was the organism’s response to a stimulus, and he was concerned with the establishment of a simple model of learning upon which more complex structures might be built. Although there was this basic similarity and both were pioneers in the scientific study of learning, their approaches to the same problem reflected their different philosophies. Pavlov, one might say, arranged the environment, in the example of the dog, in such a manner that a particular form of behaviour (salivation) was forced to appear; whilst Thorndike provided an environment in which a variety of responses could occur and the learning of one type of behaviour would depend largely upon chance and satisfaction.

Thorndike’s basic experiment was to observe the behaviour of cats confined in a cage, release from which could be effected by the lifting of a latch or some other simple device. The cat’s initial behaviour tended to be of a random nature; it would claw, scratch, bite and push its paws through the bars until one particular aspect of this behaviour activated the release mechanism. When the cat was returned to the cage repeatedly, it gradually reduced the time it took to release itself by eliminating the non-effective responses. Eventually the cat would perform only the effective response to secure its own release. Learning had taken place which was gradual and which was the result of the organism’s reaction to the environment. It should, however, be noted that this gradual learning process, whilst it may be effective, is not always the most efficient.

Thorndike suggested that the cat, by going through its repertoire of behaviour patterns which already exist, will learn to make the most effective response. As a result of his experiments he proposed three principal laws of learning as follows:

1. Law of Effect The first part of this law stated that when a number of responses are made in a particular situation the response which is followed by a feeling of satisfaction, a reward, is more likely to be repeated in a similar situation. In other words, a response to a particular stimulus will by its very success lead to the strengthening of that particular bond. He also stated, in the second part of this law, that responses which were unpleasant or brought little or no satisfaction would not recur. This is, in effect, the rationale behind rewards and punishments.

2. Law of Exercise Here Thorndike stated that the responses which occurred most frequently could be strengthened. At first sight this would appear to be valid and to justify constant repetition in school, but the mere mechanical performance of one particular response, without some conscious coupling of the output to the input of the process, that is, ‘feedback’, will not necessarily result in improvement.

3. Law of Readiness This was perhaps the weakest of these three laws. Thorndike proposed that when a response was ready to be linked to a particular stimulus (ready in the sense of the necessary nerve structures being connected) discomfort would be the result. We shall see in a later chapter that more recent physiological studies on the ‘all or nothing’ principle regarding the firing of the nerve cells (neurons) reveal the weakness of this law. The ‘synapse’ where the nervous impulse from one neuron passes to another can either take place or not take place. There can be no feeling of discomfort in these circumstances.

Thorndike was a prolific writer but perhaps his most valuable contribution to learning was a modified Law of Effect. The main modification that he made was his rejection of the second half of this law which dealt with the effect of punishment. In general, modern educationalists accept that rewar...