![]()

1 Business and sustainability

Background issues

1.1 The challenge of a sustainable world

The term “sustainable development” (SD) entered the political mainstream in 1987 with the publication of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland) report (WCED, 1987), with its reference to meeting the needs of the present without reducing the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This definition placed the social dimensions of development – particularly the persistence of poverty and the disparity in incomes between North and South – at the forefront, while recognizing that the environment needs to be protected and sustained to enable it to support the desired economic and social development. Since that report was commissioned by the UN General Assembly in 1982, it is easy to show that on the various indicators of sustainability selected by the WCED (Table 1.1), there has been little progress on most and some have even worsened. On the social aspects, global poverty continues while food supply has barely kept up with population growth. On environmental sustainability, while the ozone hole may have started to recover and locally acute pollution problems have been resolved, deforestation and desertification have accelerated since 1982, ecosystems and ecosystem services are increasingly under stress, and global warming and climate change have moved from credible scientific hypothesis to demonstrated reality.

Knowledge of the state of the world and its environment is better than it has ever been before; yet it appears that we are unable to fully absorb and act on this knowledge to find a way of reducing the overall impact of human activities on the planet. While some of the many international agreements relevant to environmental sustainability have succeeded in addressing specific problems,1 those relating to the Earth as a system have had less impact – effective measures to slow the loss of biodiversity and forests, or the spread of deserts remain under negotiation; generic international action on resource depletion is not even under discussion, and the limited progress under the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) has demonstrated the monumental task of dealing with environmental sustainability at the global level, even where the international legal framework exists.

Table 1.1 Trends identified by WCED (1987)

Hunger and poverty increasing | Literacy not improving |

Lack of safe water and shelter | Lack of fuel |

Gap between rich and poor widening | Desertification |

Deforestation | Acid precipitation |

Greenhouse gases and global warming | Ozone hole |

Toxic materials and the food chain | |

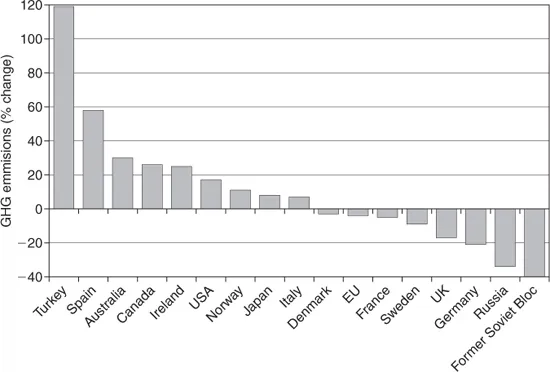

Focusing on the FCCC’s Kyoto Protocol, Annex 1 countries should reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 6 per cent by 2008–12. Some countries (USA and Australia until 2008) refused to ratify, some (e.g. Canada) have stated that even though they ratified, they will not comply. Others (including Japan) are finding great difficulty in meeting the targets; only some EU countries are on track to comply (Figure 1.1). Of the latter, most are only able to comply because of economic restructuring rather than environmental policies. While the industrialized world demonstrates its inability to meet an average 6 per cent reduction in GHG emissions, global carbon dioxide emissions have risen by ~40 per cent since the Protocol was agreed, and the annual increase of 0.9 per cent over 1990–99 jumped to an average annual growth of 3.7 per cent from 2000 to 2007 due to rapid economic growth in newly industrialized countries and the rampant burning of forests in Indonesia, Brazil and elsewhere (Global Carbon Project, 2009). The latest estimates for 2010’s emissions suggest a record 6 per cent increase in carbon dioxide emissions over 2009 (US DOE, 2011).

Figure 1.1 GHG emissions (% change 1990–2007) (source: adapted from UNFCC: Report on National Greenhouse Gas inventory data from Parties included in Annex I to the Convention for the period 1990–2007).

While GHG emissions have been accelerating, G8 world leaders have recognized the gravity of the climate change threat by adopting challenging goals for 2050 which would require industrialized countries to reduce their emissions by 80 per cent.2 The gap between such aspirations and the reality of current trends is thus becoming stark, and the outcome of the Climate Change Convention’s meeting in Copenhagen in 2009 demonstrated again how far the political response lags behind the trends identified by the science. Just before that meeting, the latest scientific studies suggested that current paths are still on the “worst case” scenario of a 6 °C rise by 2100 (Le Quéré et al., 2009).

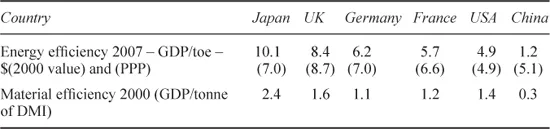

We can use Japan as an illustration of some of the challenges involved. Japan enjoys a good reputation for energy efficiency. As can be seen in Table 1.2, the amount of GDP produced per unit of energy consumed is higher than that of many other OECD countries, and considerably more than in China. Japan can also claim a similar lead in the efficiency with which it uses other natural resources – its resource productivity (RP). Table 1.2 shows Japan’s RP to be up to double that of other OECD countries, and the gap compared with China is even larger.

Among the factors contributing to efficiency are government policies introduced after the 1970s oil shock and developed to reduce Japan’s dependence on resource imports. These include:

• a legal framework aimed at a “resource-cycling” and “energy-efficient” society;3

• various government-funded initiatives such as eco-towns, Top Runner;4

• technology-push such as the many R&D programmes administered by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO);

• most recently, market-pull for low emission vehicles and efficient electrical appliances via an “eco-points” system, purchasing grants and vehicle tax reductions.

Table 1.2 Energy and resource efficiency

Sources: International Energy Agency (2009); MOEJ (2006); Xu and Zhang (2007); World Resource Institute (2005).

Notes

Toe: tonne of oil equivalent; DMI: direct material input; PPP: purchasing power parity.

These have created a framework in which incentives for innovation have been created towards a more sustainable economy – i.e. one in which resource and energy flows are more efficient. Some of Japan’s technologies and companies now offer world-leading “green technologies” in automotive, electrical goods and other fields. One indicator of progress in this field is the degree of efficiency improvements from the Top Runner policy in Table 1.3, where improvements range from 21.7 per cent to 98 per cent over eight to ten years.

With the impressive reductions in Table 1.3, an observer might be forgiven for assuming that Japan would not find too much difficulty in meeting the Kyoto target of a 6 per cent reduction! However while individual equipment has become more efficient, the trends in the “real” economy where such equipment is deployed have been in the opposite direction. As Table 1.4 shows, despite the availability of low energy equipment, there has been a substantial failure to constrain overall emissions in all sectors of the economy apart from industry. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the success of innovation-forcing regulations has been limited to those areas of particular focus such as those in Table 1.3, and has not spread to the rest of society and business. Thus even though hotels, offices and homes are using some high efficiency equipment, the overall energy efficiency of the system within which the equipment is deployed remains low, and may even have worsened, leading to rises in overall emissions.

Turning to resource productivity, progress has been made at the level of the overall economy as shown in Figure 1.2 where the amount of GDP produced per unit of direct material input (DMI) has grown year on year from 1990 (with the exception of 1998–2002), so that the economy is 80 per cent more resource efficient than 20 years earlier. Progress year on year has also been achieved with the recycling rate, although this is still only just above 12 per cent (Figure 1.3).

Nevertheless, the continued high dependency of Japan’s economy on imports is illustrated by its material balance shown in Figure 1.3. With 41.5 per cent of the 1.819 billion tonnes of resources consumed being imported, Japan exerts a significant impact on the global environment outside Japan through the demands it makes on the world’s forests, fish, minerals, oil, etc. This is often expressed as an “ecological footprint” which measures the area which would be needed to supply the sustainable needs of one person, and to dispose of the associated wastes. Some illustrative footprints are given in Table 1.5, where it can be seen that Japan exerts a total footprint area five times its own territory – in effect appropriating four times Japan’s area from other countries for its own use. This gives a feel for the scale and importance for the world as a whole of Japan’s national consumption. Of course, as indicated in Table 1.5, Japan is not alone in this and most industrialized countries are in a similar position.

Table 1.3 Energy efficiency improvements

Equipment | Improvement (%) | Period |

TV sets (CRT) | 25.7 | 1997–2003 |

Video cassette recorders | 73.6 | 1997–2003 |

Air-conditioners | 67.8 | 1997–2004 |

Refr... |