![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The sea too was very full. It was nearly high tide; the waves were rolling very tall, with light like a menace on the nape of their necks as they bent, so brilliant. Then, when they fell, the fore-flush in a great soft swing with incredible speed up the shore, on the darkness soft-lighted with moon, like a rush of white serpents, then slipping back with a hiss that fell into silence for a second, leaving the sand of granulated silver. … Incredibly swift and far the flat rush flew at him, with foam like the hissing, open mouths of snakes. In the nearness a wave broke white and high. Then, ugh! across the intervening gulf the great lurch and swish, as the snakes rushed forward, in a hollow frost hissing at his boots. Then failed to bite, fell back hissing softly, leaving the belly of the sands granulated silver.1

– D.H. Lawrence, Kangaroo

The little seaside town of Thirroul, Dharawal in the local aboriginal language, sits with the ocean on one side of it and cliffs on the other, 40 miles south of Sydney. I used to live there. This, this, is what the breaking waves are like: what they feel like, what they sound like, their intensity. But the author was not an Australian. David Herbert Lawrence visited the town with his wife Frieda for six weeks in the winter of 1922. It scarcely seems credible that in six weeks he drafted a novel of 150,000 words: veritable torrents of Lawrence. Everything he had seen and thought and heard seems captured here, eloquent and half-digested, from the sounds of the ocean and the silence of the bush to the modes of speech and the brittle humour of those who lived next to them. But Kangaroo is not just a stunning evocation of place. I want to bring this novel – ultimately, indeed, this very passage – to bear on the relationship between literature, justice and the rule of law.

The rule of law is a global issue of both theoretical and practical importance. One aspect which has long been of interest to me, and which underscores the discussion of this book, involves the question of what it means to talk about justice in the context of formal legal judgments. This is a critical aspect, of course, of the rule of law: the notion of how judicial decision-making should be understood, the extent to which and in what ways we are right to think of it as constrained, and whether ‘the rule of law’ thus furthers or, on the contrary, inhibits the realisation of justice. Justice, it surely goes without saying, involves much broader issues than this, including questions of social, distributive and collective justice. My focus here is the relationship between rules, judgments and justice as one central component of what we mean when we talk about the rule of law.

The rule of law is in crisis: on that point, many scholars agree.2 On the one hand, it is imperiled by the resurgence in our politics of a Hobbesian conception of untrammelled sovereignty which insists that the State’s executive power should or must be given free rein in the treatment of those who are considered the nation’s enemies – that is, that the rule of law can and must be ignored by an executive power prior and superior to it.3 9/11, terrorism, security, immigration and refugees provide relatively familiar examples of the phenomenon. On the other hand, the rule of law is said to be imperiled by those many critiques, including post-modernism, relativism and post-colonialism, which have steadily undermined our belief in the orthodox assumptions of legal positivism, according to which rules and laws are clear, certain, objective and therefore capable of constraining such power.4 All this is relatively familiar too. Some indeed allege that these two dimensions, the one political and the other theoretical, are mutually enabling: the undermining of meaning by the latter facilitates its cynical manipulation by the former.5 Eventually, even something as objective as where someone was born collapses in a rhetorical and ideological slurry of claims and counter-claims.6 The theoretical ‘left’ is accused of facilitating the political ‘right’. By working so avidly to destabilise texts and institutions, key movements in contemporary legal theory and philosophy – not just in the recent past but since the dawn of modernism 100 years ago – seem fatally to undermine the tenets of the rule of law.

Many scholars, among whom Brian Tamanaha is exemplary,7 simply reject what has been called the ‘post-modern’ critique of the rule of law. They argue that some version of positivism must be maintained if the rule of law is to continue as a bulwark against abuses of discretionary power. Important challenges to conventional approaches to meaning and certainty in law are thus either ignored altogether or attacked on purely normative grounds;8 derided or dismissed just because the rule of law could not withstand such a critique. But this dialogue of the deaf between those who care about the rule of law and those who are interested in cultural, social and legal theory cannot go on – it shows a wilful blindness in the former and dooms the latter to irrelevance. Instead, I start from the position that the critiques of ‘rules’, language and meaning that have been accumulating not just since 1968 but for 100 years or more, cannot be wished away. The challenge – a real political as well as intellectual challenge – is to address more seriously their implications for the rule of law.

In rising to this challenge I want to address a major fault-line in contemporary writing in law and the humanities between writers who have been influenced in some ways by Heidegger on the one hand and by Derrida on the other. That is a pretty crude generalisation but it will do. The shared heritage and orientation of these philosophers, their shared distance from the analytic tradition, have largely concealed the fact that they suggest profoundly divergent responses to questions about the nature of legal judgment and the future of the rule of law. I want to sharpen the debate and clarify an under-appreciated distinction. The pragmatism that I take from Derrida gives us resources through which to re-imagine the rule of law while Heidegger’s does not. In particular, there seems to me powerful echoes in the latter of a jurisprudential tradition in which the idea of rules would be superseded or perfected by an entirely unbound and unlimited justice. Indeed, as we will see, this idea of justice as something that transcends and opposes the rule of law is common across a wide spectrum of legal writing. We hear it in the cultural study of law, where ‘literature’ is so often the cavalry which arrives to oppose and complete the law by incorporating those ‘essential human insights lost to formal thought’.9 In a lot of other legal theory too, such as in the critical legal studies movement, the word ‘politics’ performs a similar function; ‘politics’ which solves the problem of justice that the various critiques have shown that a structure of legal rules cannot. More recently the word used has been ‘ethics’; again too often a black box which points to something outside of the parameters of legal rules but which can, mysteriously, redeem the law and finally achieve justice.10 Throughout this book, I use the terms ‘romantic’ and ‘romanticism’ to identify this appeal to some transcendent idea or ideal capable of overcoming, exceeding or curing the law. There are then two foils in this book: positivism on the one hand, and the romantic impulse against which it has so often been pitted on the other. Kangaroo Courts asks what it means – particularly in relation to the rule of law – to cleanse our palette of both.

In fact these themes and controversies are not new. They converged at a moment in our intellectual and social history that remains critical for any understanding of them: modernism, specifically in the context of the aftermath of the Great War of 1914–18. Modernity and modernism are related, but they are not the same thing. This book considers what has often been called ‘the crisis of modernity’ and attempts to show how modernism – the outpouring of creativity in thought and in the arts which responded in various ways to that crisis – has continuing implications for how we understand the relationship between judgment and the rule of law, and between law and literature. And here, as will become apparent, the influential work of Mikhail Bakhtin and D.H. Lawrence, serve as my lodestars. Neither has received much attention in legal studies. Yet they speak directly to the problem of justice and of judgment in the wake of modernism, and they each endeavour to show the importance of literature in leading us through the very impasse which remains evident today – even in something as mundane as the rule of law. No less than Lawrence in the wake of the Great War, we still face the terrible problem of what to do once we can no longer believe in our old habits of thought: for belief has died though the habit of believing lingers on. This problem is not to be faced by attempting, through an act of will, to resuscitate our old beliefs or romantic notions; but rather by working out how to keep going without them. Lawrence wanted to know if the twentieth century had rendered politics outmoded or irrelevant. I want to know if the rule of law has likewise been rendered ‘quaint’, ‘outmoded’11 or irrelevant.

Kangaroo Courts and the Rule of Law: The Legacy of Modernism thus reflects my efforts to bring together three questions in legal scholarship which have become increasingly urgent in the last few years: a substantive question – what is the future of the rule of law?; a theoretical question – what is the difference between two main threads in what is now called ‘law and the humanities’?; and a methodological question – is the study of law and literature still relevant? These questions are critically important and interrelated. Each gives us resources to better understand and answer the others. The fundamental question seems to me to be whether we can recast the rule of law in light of the critical turn of the past century, rather than being steadfastly opposed to it. This book tries to build a distinct conception – a truly modernist conception, and ultimately a literary conception – of a post-positivist and post-romantic rule of law. In the process I hope to change how we understand the practice of law and literature, and to reframe what we understand to be the goals of legal judgment.

D.H. Lawrence offers an uncanny point of entry into all these interrelated issues of politics, philosophy and writing – indeed a subterranean warren that secretly connects them. That Lawrence was an unusually beautiful writer is not in doubt. But Lawrence’s fertile visit to Australia coincided with an explosive outburst of writing about politics, about psychoanalysis and about literature that placed Lawrence at the heart of the currents of change and anxiety transforming all these

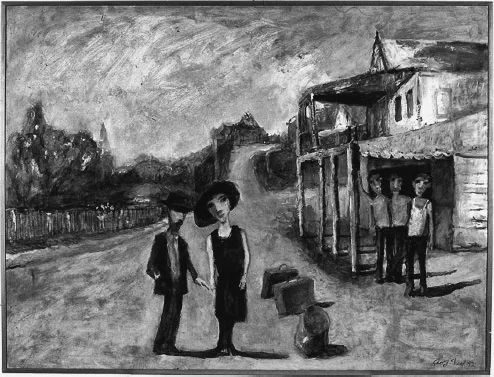

Figure 1.1 Garry Shead, Thirroul (D.H. Lawrence Series12)

fields. Kangaroo, written in 1922 and published the following year, is the strange and misunderstood apotheosis of this work and this moment: it brings together a theory of literature with a theory of politics and a theory of psychology at a critical juncture in the history of all three: on the very cusp of modernism in literature and just when the search for a way to break through the impasse of modernity was most keenly and widely felt. He saw the crisis of literature and the crisis of authority as interconnected, and he was right.

Chapter 2 provides a preliminary overview of the domain of law and literature and argues for its reconfiguration. In some ways the rest of the book is a case study intended to expand the methodology introduced here. Chapter 3 sets Lawrence’s work against ‘the crisis of modernity’ which engulfed the European imagination at the end of the Great War. This crisis, as an aesthetic, a religious, a legal and a political phenomenon, Lawrence saw all too clearly and felt all too keenly. In a very real way, the crisis was for Lawrence personal. Kangaroo, which I introduce in Chapter 4, was the novel he wrote that best attempts to come to terms with it.

Chapter 5 sees recent debates about judgment, justice and the rule of law as the aftershock of this cataclysm. In its thorough-going rejection of positivism, recent work whether influenced by Derrida’s ‘Force of Law’13 or by Heidegger and Levinas14 hearken back not only to a shared philosophical lineage via Nietzsche but to all those writers – Simmel, Weber and Collingwood as well as Schmitt, Lawrence and Bakhtin – who during and after the War already saw the limitations and blind spots of positivist thought. At least some of these writers, then and now, came to dismiss the rule of law as a perversion of justice. Yet, while Derrida and Heidegger offer a sceptical argument against the positivist rule of law and both render it vulnerable to attack, there is a crucial difference between them. Although not everyone will agree, this difference lies in Heidegger’s romanticism and transcendentalism as opposed to Derrida’s pragmatism and humanism: the enchantment of the one and the disenchantment of the other. Kindred in many ways, these two strands of contemporary anti-positivist legal theory offer very different resolutions to the p...