![]()

| 1 | THE URBANISATION PROCESS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES |

Although it is axiomatic to state that houses comprise the greater part of any city, this sheer physical dominance does not mean that housing provision is important enough to be discussed in isolation from other aspects of urban life. Housing as a commodity has many different characteristics so that its importance and nature vary from producer to consumer. Castells (1977) has argued that the ‘housing crisis’ does not derive from exploitation but from the mechanistic relation between supply and demand. However, in the Third World, where massive shortages of conventional houses exist, the socio-economic characteristics of the production process determine the nature of this ‘crisis’ and these almost inevitably involve exploitation. As such, housing provision is a function of the national and international structural relationships which have given rise to Third World cities; it is not unique and shares many features with other important and diverse components of urban life, such as the distribution of political power, or the availability of employment.

In this opening chapter it will be useful to examine the general characteristics of the urbanisation process in the Third World in order to identify some of the broader forces involved. Later chapters will focus on more specific issues, such as housing provision per se and its individual components, illustrating the main arguments with reference to case studies. It is important to remember, however, that the structural relationships discussed in this initial overview are omnipresent throughout the spatial hierarchy.

The Statistical Dimensions of Urbanisation

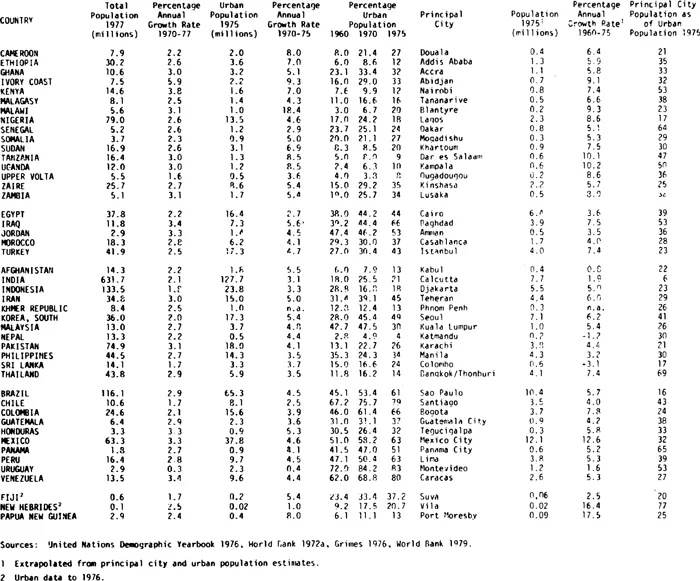

Most statistical information on an international scale is assembled by multinational organisations such as the United Nations or the World Bank. The national data collated in such summaries often exhibit considerable differences in both working definitions and reliability, and where possible some form of standardisation is employed to enable more useful international comparisons to be made. Thus ‘urban’ data cover settlements of at least 20,000 inhabitants, whilst ‘cities’ are taken to be urban agglomerations of more than 10,000 people. These figures are essentially population counts for official administrative districts and may not correlate either with the actual metropolitan area or with the socio-economic functions of the settlement.

The general scarcity of uniform and reliable data in the Third World also means that aggregate tables may vary widely in the accuracy of their individual components. This is particularly true for intra-urban social phenomena, such as health indicators or housing quality. The latter is usually poorly defined and gives rise to very misleading comparative figures; for example, most tabulations which purport to summarise both slum and squatter populations invariably cover only squatter settlements simply because they are visually more distinctive and appear easier to record. There are relatively few criticisms of such international aggregations and their data are too readily accepted by eager quantifiers. Admittedly, neither the United Nations nor the World Bank claim complete accuracy for their statistical compilations but the prestige of such information sources often lends a credibility which far exceeds reality. Criticisms and data peculiarities may be found in almost every country in the Third World and it would serve no useful purpose to itemise them all at this point. Suffice it to say that basic caveats do exist and should be borne in mind when national or international statistics are utilised. Where possible in the broad overview which follows, such data will be supplemented by information from detailed subnational surveys.

Basic Characteristics

It is advisable when analysing urban growth to distinguish at the outset between the absolute numbers and the relative rates or proportions which are involved. The rise in the urban proportion of total population in the Third World does not appear to be unduly remarkable if comparisons are made between the developing countries and industrial nations during their initial growth period. Over the last two decades the average annual rate of population growth in the Third World was 2.5 per cent (World Bank 1979); the comparable figure for developed countries during their most rapid growth periods was 3.1 per cent. However, the averaged figure for the Third World covers a much wider range of demographic and urban circumstances than that for developed nations, making excessive generalisation on this scale of somewhat dubious value. The individual statistics in Table 1.1 are more indicative of the real situation and illustrate several important characteristics.

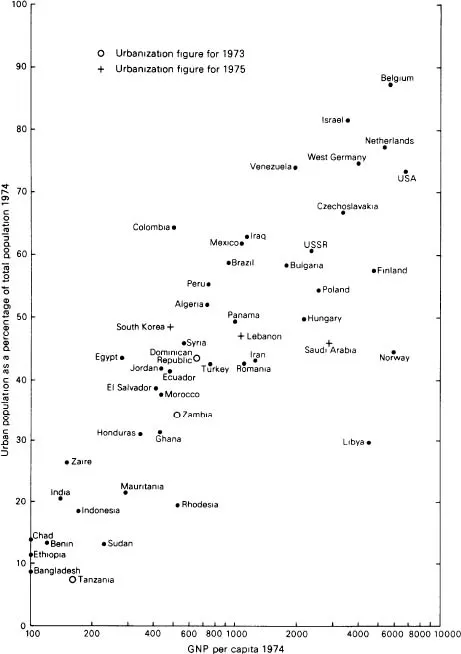

First, contemporary urban growth in developing countries has such large absolute dimensions as to distinguish it clearly from nineteenth-century trends in Europe and America. Between 1800 and 1900 the total city population of Europe (including Russia) increased by some 4.3 million, whereas in the less developed countries of Asia the urban population has risen by 160 million in just the last twenty-five years. Moreover, rural populations have also been increasing at unprecedented rates throughout the Third World: at equivalent growth periods in the developed countries few rural populations showed comparable expansion. The overall scale of urban development is therefore more massive than ever before and is likely to continue to accelerate throughout the present century since many Asian and African countries have yet to reach their forecasted maximum rates of urban growth. In general terms the expansion in urban populations can be correlated with economic growth (Figure 1.1), although it would be unwise to infer a causal relationship either way. The precise nature of the connection between the two elements has generated strong discussion around contrasting arguments which will be considered later in this chapter.

Table 1.1: Growth in Total, Urban and Principal City Populations Between 1960 and 1975 in Selected Developing Countries

Figure 1.1: Urbanisation and Economic Growth, 1974

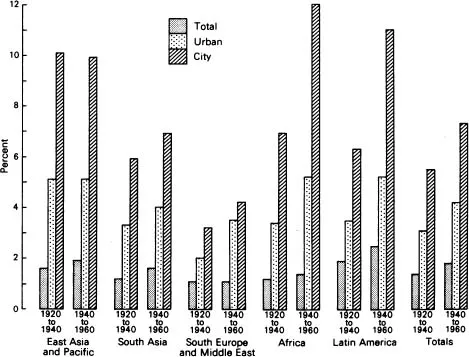

One less controversial characteristic which can be identified in most developing countries is the allometric nature of urban growth, i.e. the way in which the largest cities have experienced the most rapid increase. In most regions the development of cities with populations in excess of 100,000 has been virtually double that of overall urban expansion (Figure 1.2). This is not to say, however, that definite correlations may be drawn up between size, economic functions and urban growth rates. Considerable variation again exists from country to country in relation to different economic and political situations.

Figure 1.2: Regional Growth Rates of Total, Urban and City Populations

This general comment can also be extended to the phenomenon of primacy in which one city is seen to dominate the urban hierarchy within a particular country. Linsky (1969) has argued that high urban primacy occurs most frequently in small, populous, poor countries with colonial histories, but here again variations exist. A considerable degree of primacy also exists in countries such as Hungary, Denmark and Britain; on the other hand, Thailand, where the capital Bangkok is almost 30 times larger than the second city of Chieng Mai, has never been a de facto colony. Many developing countries do not, in fact, exhibit any marked urban primacy at all, a characteristic which tends to undermine the mathematical generalisations on urban primacy attributed to the Third World.

Such conclusions call into question the validity and utility of related concepts, such as the rank-size rule and urban hierarchy, as well as the notion of primacy itself. As Janet Abu-Lughod (1973a) has pointed out, most of the standard measures which have characterised such analyses have been derived from a period of European urban-industrial growth which was distinctly abnormal compared to that which preceded or followed it. She has consequently illustrated that the urban primacy and imbalance, which supposedly characterises the various Middle Eastern countries, disappears when the artificiality of recent political boundaries is ignored and the region is examined as a whole. Unfortunately, having criticised Western notions of primacy and hierarchies, Abu-Lughod goes on to describe a regional urban hierarchy in the Middle East, ranking downwards from Cairo, through the subregional centres of Baghdad, Beirut and Damascus to the subnational cities such as Homs, Kirkuk and Basra. Not only does this hierarchy contain all the traits previously criticised but it also ignores the Israeli cities in the region.

Santos (1977a: 16) has been even more critical of contemporary geographical theory on urban growth and urbanisation, taking the stochastic models related to innovation diffusion severely to task. Contrary to prevailing thought on this subject, Santos claims that the direction and nature of development diffusion is a function of external influences and laws based on the interest of the sender in order to maximise results (profits). Quantitative models may also be criticised for their failure to take social structures and relationships into consideration, as well as their neglect of historical information. In the context of the Third World, these factors are of crucial importance in attempting to understand the nature of the development process. Santos (1977a: 18) again summarises the situation succinctly: ‘an essentially dynamic phenomenon is reduced to a morphological piece of data. Process is reduced to a form. Reality is deformed into bastardized mathematical models fit [sic] into a Procrustean bed.’

The variation which characterised and has affected the urbanisation process in the Third World argues against excessive generalisation, particularly along Western lines. So many criticisms can be made of the facile typologies produced to date that the value of such work must be seriously questioned. The remainder of this chapter will accordingly concentrate on offering an explanatory framework within which the urban growth characteristics of any one city or nation may be usefully placed.

Causes of Urban Population Growth

Natural Growth

About half of the population growth in Third World cities is the result of natural increase – rather more than half in Asia, rather less in Africa. The main cause of rapid natural growth in developing countries has been the sharp decline in mortality, particularly in infant mortality, which has occurred over the last two decades. The accumulation of knowledge and skills in the various fields of medicine, hygiene and nutrition together with their diffusion throughout the Third World has been the principal reason for this fall in death rates, although there are still many countries, particularly in Africa, which have not yet experienced the full benefits. In contrast, birth rates are affected by a much more complex mix of biological, social and economic factors and, in general, have remained high. Annual growth rates have thus increased dramatically over the last twenty years and average 2.5 per cent for developing countries as a whole. Considerable variation exists, however, so that in Latin America and Africa many populations are increasing at annual rates in excess of 3 per cent, with some, such as the Ivory Coast and Kenya, nearer to 4 or 5 per cent. The significance of these rates of increase may be gauged from the fact that the population of the Third World is likely to double in only twenty-five years.

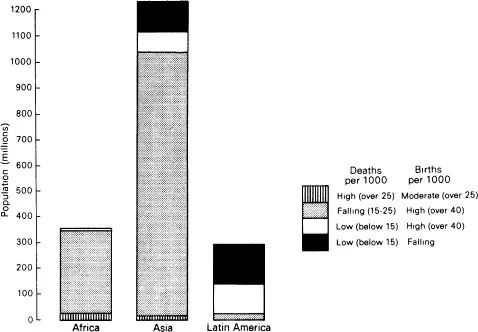

The variations in birth and death rates which exist in developing countries, when taken together with the demographic transition which the developed nations have experienced, make possible the production of a fourfold classification of growth rates (Figure 1.3). The majority of developing countries fall into the first two groups and it would seem that the most rapid phase of their population growth is either being experienced at present or is yet to come. However, over recent years evidence has appeared to modify this pessimistic prognosis (McNamara 1977). Between 1960 and 1977 birth rates in the less developed countries declined on average by about 13 per cent. Moreover, this fall in the crude birth rate has been fairly widespread, occurring in 77 of the 92 developing countries for which estimates were available; in addition the rate of decline is accelerating.

Although these general figures seem encouraging they do mask important variations in both regional and national trends. The greatest reductions in the crude birth rate have occurred in the countries with the smallest populations and in several of the largest nations, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nigeria, the fall in birth rates has been minimal. But whilst the downward trends in fertility levels are welcome, they are not yet large enough to allay current fears over the anticipated pressure on world and national resources that population growth must create. It is important therefore that the determinants of the decline in birth rates be identified and incorporated into future birth control programmes.

It is fairly clear that the demographic transition in developed countries was paralleled by both mortality decline and socio-economic development. This relationship has consequently been simplified to one in which fertility decline is assumed to be dependent on the level of income per capita. However, the relationship is far more complicated than this and the circumstances that affect its character in the Third World today are considerably different from those which operated in developed countries. In general, five factors have been identified as being important in the current downtrend in Third World fertility rates. The first is improved health, particularly in infants, since the survival of children encourages parents to think positively about the size of their family. A second factor is the spread of education which makes both men and women more receptive to new ideas and more perceptive of the benefits of family planning. This phenomenon is closely linked to the third element which is the enhanced status of women.

Figure 1.3: Vital Statistics for Developing Countries, 1955

In addition to these specific family planning factors, there are two more general development features which can be linked with declining birth rates. One is the broader distribution of the benefits of economic growth. If the lower-income groups can be convinced that their living standards will rise, not just absolutely but relatively, then they will be more likely to change their opinions concerning family size. However, as discussed below, economic development in the Third World has not always been accompanied by an egalitarian distribution of benefits and the increased diffusion of such rewards remains one of the most important indirect ways in which governments can encourage family planning. The other feature of modern development which has affected fertility is urbanisation. The move to the cities has drastically changed many of the traditional attitudes towards family size and function. In rural areas large families ensure a cheap labour supply but in the city they simply increase the dependency ratio and make housing more expensive. In addition, life in the city increases access to all of the other factors which are related to diminishing birth rates. At present, therefore, the indications are that lower levels of fertility are associated more with specific features of development rather than with the general level of economic wealth. McNamara (1977:25) provided convincing proof of this in his comparison of Korea and Mexico; for the substantially higher overall national income of the latter has failed to bring about either fertility reduction, or other socially desirable changes.

Despite such evidence, birth control programmes have continued to be advocated on the basis of the economic benefits which they are likely to bring about. This approach has been justifiably criticised because it is based on the assumed relationship between economic and demographic change which took place in industrial nations. However, the precise nature of this relationship is still imperfectly understood, and it would appear that economic development preceded the deceleration in population growth. As there were no birth control programmes during this period in the developed nations, one must assume that the improved standards of living, change in socio-economic values and increase in education brought about the reduced birth rate which occurred. If this is so, then the developing countries of the Third World are being asked to reverse the process and control fertility in order to increase economic benefits. In short, what the British or German family achieved voluntarily, the Indian or Nigerian family is expected to undergo in response to paper promises of prosperity.

There is no guarantee that developing countries will eventually follow the demographic transition experienced in the West, and the authoritarian attempts to impose admittedly humanitarian objectives on such societies place heavy demands on the individual family. This raises the important question of whether poor families in the Third World see demographic issues in the same light as the middle- and upper-income groups who determine national policies. To families in rural areas, the ‘dependency burden’ of children may well mean a less arduous life. Although similar agricultural logic cannot be applied in all situations, it does illustrate that the poor do not have large families without reason. Indeed, their very poverty forces them to make rational, pragmatic decisions.

At present the number of developing countries with government-supported birth control programmes is limited. In 1975 there were 34 with official programmes designed to reduce birth rates. Mor...