![]()

I.D.H. Shepherd and C.J. Thomas

The aim of this chapter is to focus attention on the recent academic literature relevant to the analysis of spatial patterns and processes associated with consumer shopping behaviour in Western industrial societies at the intra-urban scale of investigation. The literature relevant to this subject is extensive and a considerable variety of approaches and methods of investigation exists. This review describes and evaluates the range of approaches adopted and suggests the manner in which they are interrelated. Particular attention is paid to the recognition of significant gaps in current knowledge and, where appropriate, suggestions are made to direct future work to topics deemed to be of academic or practical planning significance. The emphasis of the review is on geographical sources, but the increasing interdisciplinary nature of this topic is recognised and appropriate excursions are made into the marketing literature — which emphasises economic, psychological and sociological concepts and methods — and into psychology and anthropology. However, no attempt is made to cover the growing literature emerging from the field of urban modelling. This work involves the development of highly sophisticated mathematical and statistical models and aspects of this work, as exemplified by Wilson (1974), Batty (1978) and Openshaw (1975, 1976), are clearly relevant to the investigation of consumer spatial behaviour. This work is beyond the scope of this particular review, which tends more towards an empirical emphasis, but it is more fully covered in the next chapter.

The emphasis of the early studies in the geography of retailing in cities was concerned with the empirical recognition (Proudfoot, 1937) and explanation, initially via theory (Berry and Garrison, 1958; Berry et al., 1963) of regularities in the spatial system of shopping centres. Shopper behaviour as such was rarely specifically considered. Instead, the system of centres was assumed to be in a state of adjustment with the distribution of consumer demand across the city. The implication, which is made explicit in central place theory, is that in normal circumstances a consumer will tend to shop at the nearest centre offering the good or service which he requires. Thus, from a knowledge of the distribution of consumer demand and the spatial structure of the shopping system, the vast majority of behavioural interaction might be predicted with ease. If this notion is correct, it clearly provides a relatively simple model for retail planning proposals, whether they emanate from commercial or public organisations. The strength of the relationship between structure and behaviour was assumed rather than demonstrated and did not bear close examination in either rural (Thomas et al., 1962) or urban (Clark, 1968) situations. In addition, it further implies that ‘consumer sovereignty’ is the major determinant of the availability of spatial shopping opportunities. This clearly overstates the case in the period after 1960. Many major developments in the organisation and control of retailing after that date (Dawson, 1977) have initiated changes in the spatial pattern and organisation of shopping facilities which do not necessarily reflect consumer pressure. In North America the growing scale of organisation of retail firms combined with relatively ineffective planning controls are highly significant, while in Britain a stronger planning framework combined with planning ideals developed in accordance with some of the concepts of central place theory are of considerable importance (Davies, 1976).

As a result of the recognition of the inadequacy of early simplistic behavioural assumptions, considerable interest has grown in the study of consumer spatial behaviour, and a great variety of approaches and methods of analysis now exist. However, the resulting corpus of literature is not well integrated and a refined theory of consumer spatial behaviour does not exist. Nevertheless, it might be suggested that a unifying theme can be recognised in this work in that the aim of much of the research is to explain behavioural patterns and their variations and, ultimately, to predict future relationships in an attempt to refine planning policy proposals.

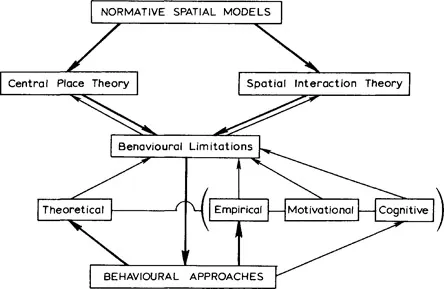

This review is broadly structured in a similar way to that of Thomas (1976). A basic distinction is made between normative spatial models and behavioural approaches and these are further subdivided into the categories indicated in Figure 1.1. Most of the literature falls conveniently into these categories for the purposes of preliminary discussion, although it is interesting to note that recent studies have increasingly given attention to more than a single category, while additional elements can be recognised in the literature which has emerged since 1974.

Figure 1.1: Interrelationships between Alternative Approaches to the Study of Intra-urban Consumer Shopping Behaviour

Normative Spatial Models

The normative spatial models represent an aggregate approach to the study of consumer spatial behaviour. Groups of people, usually defined geographically by place of residence, are considered to behave in accordance with postulated assumptions or norms which are considered to result in optimal patterns of spatial behaviour. The models most relevant to the current context are those associated with central place theory and spatial interaction theory.

Central Place Theory

Since the seminal work of Christaller (1933), interest in central place theory in geography has been considerable and a prodigious amount of literature has been generated. However, the great majority of this work has been concerned with the deductive theoretical basis for the development of hierarchical systems of service centres at the inter-urban scales and the empirical testing of the validity of such systems in the real world. Comprehensive reviews of such work are available elsewhere and their reiteration here is unnecessary (Beavon, 1977). Within this body of literature, interest in consumer behaviour has been secondary and patterns of behaviour have been largely inferred rather than empirically derived. Human behaviour has been assumed to conform to the economic man concept, and both suppliers and consumers of services are credited with perfect information and the ability to make economically rational decisions. The theory assumes that an optimal location decision is made by the suppliers of services and that every consumer undertakes an economically rational journey to consume (Pred, 1967). The suppliers’ decision is assumed to be determined by the ‘threshold’ concept, which states that a service will not be provided in a location unless a local market capable of supporting it at a profit exists. The market population normally will be located beyond the maximum sphere of influence (range) of any other centre supplying the service. The journey to consume is assumed to be determined by the range. The consumer will normally travel to the nearest centre within whose range he happens to live, in order to minimise the time-cost budget of the journey.

Interest currently centres on the latter concept which gives rise to the nearest centre hypothesis as the basic behavioural tenet of central place theory, i.e. that a consumer will visit the nearest centre supplying a good or service. However, it is now apparent that this inference results in a serious overstatement of behavioural realities. A considerable amount of information now exists which demonstrates the limitations of the hypothesis in the Western urban context (Clark, 1968; Ambrose, 1967; Day, 1973), so that at best it can be considered only a partial explanation for consumer shopping behaviour. For example, Clark’s (1968) study of Christchurch shoppers indicated that only 50–60 per cent of convenience shopping trips could be predicted by the nearest centre hypothesis.

The situation is perhaps not too surprising, since according to Pred (1967), even Christaller’s original work recognised two circumstances in which the behavioural assumption might deviate from the norm. First, shoppers may attempt to maximise total travel effort, often by combining shopping in a multi-purpose trip, rather than merely minimising the travel cost for an individual good. Thus, a consumer may obtain both low- and high-order goods at a high-order centre which is more distant than the closest low-order centre. Secondly, a shopper may travel to a distant centre if sales price savings exceed additional transport costs. It is difficult to envisage how such behavioural variations could be comprehensively incorporated into a modified central place theory.

Other features also limit the applicability of the behavioural assumption of central place theory at the intra-urban scale. Pred (1967) has suggested that consumers of services (like suppliers) are more likely to be ‘boundedly rational satisficers’ rather than ‘economic men’. Thus, consumer behaviour is considered to be constrained by the fact that the individual is likely to have an incomplete knowledge of the overall nature of the supply system and will, for many social reasons, be satisfied by undertaking journeys which will not necessarily result in an economic optimisation of potential opportunities. Thus, consumer spatial behaviour is as likely to be socially sub-optimal as economically optimal. Also, at the intra-urban scale, the range of possible alternative shopping opportunities is constantly increasing. This results from improvements in personal mobility and from increasing consumer awareness related to developments in education and advertising, and is demonstrated in the emergence of overlapping hinterlands of shopping centres at all hierarchical levels (Berry et al., 1963).

Incorporation into central place theory of behavioural variations such as these would modify the theory out of all recognition, if indeed such an exercise were possible. For this reason, presumably, little recent work on consumer behaviour has been specifically related to central place theory. In fact, the only recent article to address the nearest centre hypothesis specifically (Fingleton, 1975), based on an exhaustive statistical analysis of convenience goods shopping in Manchester, suggests its lack of applicability due to variability in behaviour related to variations in the age, car ownership and income levels of consumers. However, a recent review of intra-urban shopping patterns in British towns suggests that:

To a very large extent, the residents of British towns do use the nearest shopping centre offering a given type, quality and combination of goods and services. There are certain factors which can over-ride movement minimization, but this assumption is unusually valid: there are few spatial generalisations concerning human behaviour that are empirically so well supported (Warnes and Daniels, 1978).

However, while agreeing with the evidence behind this assertion and with its general sentiment, it is highly debatable whether such an assertion could form the basis of a comprehensive approach to the study of intra-urban shopping behaviour. The problem arises in the phrase ‘nearest shopping centre offering a given type, quality and combination of goods and services’. Given by whom? Presumably this relates to the individual shopper? If so, the ‘type, quality and combination of goods and services’ will be invariably defined by the individual shopper in terms of the required goods on a particular trip, mobility constraints on behaviour or, even more nebulously, level of satisfaction demanded. Such factors are likely to vary amongst individuals living in the same residential area, and by groups living in different residential areas with differing access to shopping opportunities. Clearly, the discussion has moved into the realms of the empirical, behavioural and cognitive-behavioural approaches to the study of shopping behaviour (Thomas, 1976). If the evidence and information provided by such studies could be successfully incorporated into a modified central place theory, then the approach implied by Warnes and Daniels might be justified. At the moment it is difficult to see how this might be accomplished and, in the absence of any direction on this point, their suggestion must remain speculative.

Thus, it appears at the moment that central place theory provides, at best, only a partial explanation for shopping behaviour in the intraurban situation and that the refinements necessary to rectify this situation are likely to prove extremely difficult. Consequently, it might be suggested that the value of central place theory in the study of consumer spatial behaviour in cities is most relevant to an understanding of the fundaments of the spatial structure of shopping opportunities, and serves as a useful pedagogic introduction to the study of consumer behaviour. However, the detailed limitations and constraints on its behavioural assumptions suggest that further investigation of consumer spatial behaviour is most likely to progress through an alternative research framework.

Spatial Interaction Theory

Spatial interaction theory offers an alternative normative model designed to explain behavioural interaction. The assumption that behaviour is explained by consumers using the nearest offering of a good or service is discarded. Instead, behaviour is assumed to be determined by a more complex trade-off of the advantages of centre size (or more generally attraction) of the centres against the disadvantages of distance (or more generally disincentive) of the consumers to the centres. This was derived from the ‘law of retail gravitation’ (Reilly, 1931) and is intuitively based on an analogy with Newtonian physics and empirical observations of shopping behaviour in an inter-urban context.

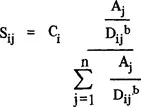

At the intra-urban scale, the wider range of shopping opportunities within relatively short distances renders the two-centre case of the original formulation inappropriately deterministic. In these circumstances, Huff (1963) considered it more likely that more than one centre will be used by the residents of a particular area with varying degrees of probability. The probability of the residents of an area using any particular centre was considered likely to vary in direct proportion to the relative attraction of the centre, in inverse proportion to some function of distance between the centre and the residential area, and in inverse proportion to the competition exerted upon the earlier relationship by all other centres in the system. These behavioural assumptions were independently incorporated into a probabilistic reformulation of the gravity model by Lakshmanan and Hansen (1965), which was designed to estimate the shopping expenditure flows between any residential area (i) and shopping centre (j) in a system:

| where | Sij | = | the shopping expenditure of residents in area i spent in centre j; |

| Aj | = | the size (or index of shopping attraction) of centre j; |

| Dij | = | the distance from area i to centre j; |

| b | = | an exponent empirically calibrated using known origin-destination data to express the distance disincentive function operating in the system under investigation; |

| Ci | = | the total shopping expenditure of residents in area i. |

The model was applied to the pattern of shopping trips to higher-order centres in metropolitan Baltimore and was found to provide a reasonable description of behavioural interaction. It was then rerun incorporating possible future residential areas and service ce...