![]()

1

CIRCULAR FRAGMENT OF A THEORY

… to speculate on what is still possible, in the domain of tonality.

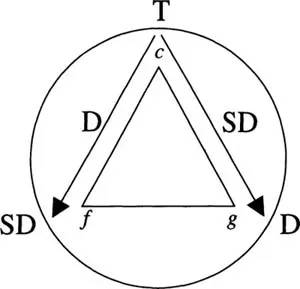

The generator of centuries of music, the holy trinity: tonic, dominant, subdominant (T, D, SD), and their extraordinarily clear functions with respect to each other; a constellation which becomes ever more mysterious, the more transparent the mutual relationship of the three poles is:

Figure 1.1

A closed circular form resting in itself, more essential than the genius that bowed to it, for it came first. A hierarchy of tones which could have ensured that the community of sounds which it controlled should be immutable once and for all. And yet one man, Schoenberg, around the time of the first world war, seemed able definitively to destroy this élite of tonal functions.

Fifty years earlier, the first bars of Tristan und Isolde had already evoked a disturbing picture: they made concrete the possibility of the non-existence of the fundament of the tonal order, namely the tonic itself. A few bars with only subdominant and dominant functions, and no tonic! At best a virtual presence, but in every case a real absence of the tonic.

So, during the conjunction of Nietzsche and Wagner –Schoenberg’s subdominant and dominant, respectively – round about and perhaps linked with the death of God, the light of the tonic began to be extinguished.

What is our situation since then, and to what extent was Schoenberg’s concept of the series really a breakthrough from the closed symmetrical world of the tonal hierarchy? Now, a century after Tristan, in a fog of total confusion, the contours of a different musical thought begin to emerge, and the suspicion arises that the original idea of the series was in fact a transformation of the tonal thinking-in-closed-forms, in which, when the loss of the tonic has really penetrated it, post-tonal music must eventually run aground.

To open up the way for this alternative musical thinking, it is necessary to take a speculative look at the dialectic of tonality and atonality.

Perhaps simply through its non-existence in our musical situation, the tonic is a constant presence, and its former historical existence remains fascinating. What is going on with that centre of gravity, that fundament of the tonal order, which for us now is just a hole into which all the notes threaten to sink, expressionless, whilst earlier they derived their expression from it?

It is striking that only the tonic (which the Chinese call ‘the King’) has extra functions in the hierarchical system, the others (SD and D) do not. The tonic is, after all, in addition to ‘itself, the dominant of the subdominant, and the subdominant of the dominant. The three poles of the system in its totality are thus mirrored in the three functions of its central point, of the tonic.

Which of the three following formulae expresses an absolute truth?

T = T

T = d of SD

T = sd of D

Without doubt only T = T, or indeed A = A; otherwise expressed: ‘I am that ‘I am, or: ‘Befehl ist Befehl’ (An order is an order).

But when a ‘given’ in a particular coherent system can be something other than itself, its absolute value becomes relative. In that sense the tonic is less absolute (and thus more vulnerable) than the dominant or the subdominant, which can only be ‘themselves’. It is this vulnerability, this possibility, unexpected but implied in its nature, of poly- and finally pan-interpretability, to which the tonic succumbed. The moment everything can be demonstrated with the tonic, the arguments turn against it: nothing is yet proven.

At this moment, now that the serial postulates are staggering in their turn, one can imagine Schoenberg’s position, how he felt himself sinking away into the maelstrom where the tonic had sunk. The horror that he felt, he describes in his letters. We also know his answer, the buoy, as it were, with which he kept himself afloat: a new ‘hierarchy of twelve notes, related only to one another’.

From this principle – analagous to the tonal formula – how can we construct a summarised picture?

A condition herein is that this yet-to-be-discovered note-constellation should contain a maximum of information in the most concentrated symbolic form. It must be, as it were, the generator, the microstructure from which all the macrostructures arise organically.

Tonal law can be seen as a series with a fixed centre. In Schoenberg’s conception of post-tonal music, this centre moves over the twelve possible notes of our tempered system, according to the laws of a series which the composer himself sets up. This series then becomes combined with its mirror-forms (inversion, retrograde, retrograde inversion).

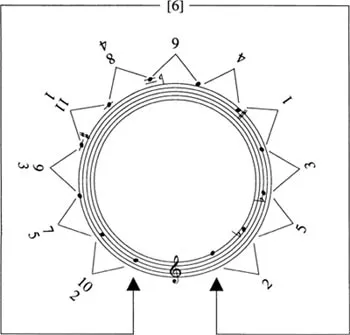

The summarised model of these principles must be a series with these mirror-forms built into it: in other words, the series must be anacyclic. Moreover, this series should also contain, in addition to all twelve notes, all the possible intervals between them – eleven, in all. The result is a so-called ‘all-interval row’ (see Fig. 1.2).

With the series, the following observations:

The sum of the intervals from 1 up to and including 11 is 66. It follows from this that the interval between the first and last notes of an ‘all-interval row’ is always a tritone (6): 66 – 5 × 12 = 6.

The point of symmetry in the series must then also always be the interval 6, whilst the mirror-point in each half-series is 3: (1/2 × 6).

This interval 6 is at the same time the symmetry-point of the octave (1/2 × 12 = 6), from which it follows that the absolute value of every possible interval in the twelve-note sphere can be expressed in the form of a number equal to or smaller than 6. This interval-value is the constant in every symmetrical all-interval row.

(Example: the series 7 4 9 2 11 -6- 1 10 3 8 5 can be written as: 5 4 3 2 1 -6- 1 2 3 4 5, I must simply indicate the direction of each interval: 5↑ 4↓ 3↑ 2↓ 1↑ -6- 1↓ 2↑ 3↓ 4↑ 5↓)

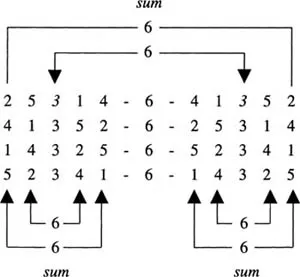

Back to the first series. The symmetry therein is indeed total:

Figure 1.2

1. |

The halves of the series mirror each other. |

2. |

All the intervals smaller than 6 are to the left, the intervals greater than 6 to the right; in other words: the directions in which the intervals are measured mirror one another. |

3. |

Both halves of the row are interchangeable: the series 413 5 2-6-25314 also works. |

4. |

The series halves can each in themselves be mirrored around the interval 3, from which the series 14 3 2 5-6-5 2 3 4 1 results. Also, the two halves of this derived series are interchangeable: 5 2 3 41-6-14325. |

With these series there are thus, in total, as many related variations possible, through internal mirroring, as are obtained through the customary external mirroring (inversion, retrograde, retrograde inversion).

5. |

Starting from the mirror-points 3, the sum of the intervals is constant, namely 6. |

6. |

Other permutations of the intervals 1 to 5 (included) do not meet the conditions. |

The schema below gives a summary of all this:

Figure 1.3

The practical musical value of this note-constellation, in which a maximum of Schoenberg’s structural principles is compressed, is inversely proportional to its theoretical value in serving as a model for symmetrical serial thinking.

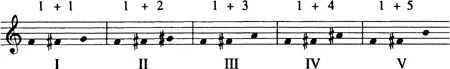

That the above series is unattractive as a compositional departure-point can be explained by the fact that it does not fulfil the ‘anti-tonal’ functions which play a great role in atonal music. What it comes down to is that, in order to neutralise tonalising centripetal effects, in ensembles of three notes at least one basic interval (the semitone) should emerge. In our tempered system, there are in total no more than five anti-tonal functions conceivable:

Figure 1.4

Measured against these functions, the series discovered earlier consists chiefly of tonalising note-groups, which lack all centrifugal effect. Thus, a series which, no matter how optimally informative for symmetrical serial thinking, is inadequate for the purpose: giving form to atonal music. Naturally this does not mean that no symmetrical row can be found (or used: Webern!) which actually meets the criterion of anti-tonality. Nonetheless, I have come across no series which can be mirrored from all sides like the one I have described above.

It would be absurd to conclude, from the discrepancy between the theoretical and the practical value of this series, that serial thinking is fundamentally a mistake: one cannot simply write off with a theoretical find the musical history of the first half of this century, which after all was determined by the obvious power of the serial principle. Nor is it for me to do this. Rather, I have described the models of both tonal and serial musical thought, in order to show how closely linked their dialectic is, how they mirror one another. So illustrated, the insight may arise that tonality cannot be resolved by serial thinking. It was for me to prove that both are hierarchic, deterministic approaches to sound, to the problem of musical form.

(1966)

![]()

2

THE DREAM OF REASON

Daedalus, son of Metion of Athens, murderer of his worthier cousin Talos, favourite and later captive of King Minos of Crete, tragic-brilliant architect of the Labyrinth of Knossus, lair of the child-devouring Moloch, the Minotaur (half man, half bull), father of Icarus (with whom he was incarcerated in his own labyrinth), chiefly responsible for the first air disaster in history (in which he lost his son, and cursed his art – the story is familiar enough), fugitive, rash builder of a temple to Aphrodite on Mount Eryx in Sicily, and finally victim of a snakebite – this ingénieur maudit is the mythological progenitor of art-engineers, mood-engineers, builders of music-boxes and synthesizers from Pythagoras to Meyer-Eppler and Moog.

At the exhibition ‘From Music-Box to Music ...