1 Eugenics and the Meritocracy

The highest fulfilment lies in submission. Of nothing is this more true than of society; and here no lesson has been more simple, and yet more painful than the fact of genetic inequality.1

It was a considerable achievement for a society to pour so much milk and so much orange juice, so many vitamins, down the throats of its children... in spite of the fact that the statistics of healthy and intelligent childhood were stretched along the curve of achievement, and only a few were allowed to travel through the narrow gate at the age of eleven, towards the golden city.2

Meritocracies are generally thought to be self-evidently good things. In Britain, a society in which merit is rewarded regardless of background or social class has long been promoted as an ideal by politicians on both the left and right, together with the closely linked concepts of equality of opportunity and social mobility. Yet when Michael Young first coined the word in The Rise of the Meritocracy, it was meant as a pejorative term, as shorthand for the technocratic, deeply divisive society that he thought would result from post-war changes in education.3 Young saw the selective system enshrined in the 1944 Education Act as a biopolitical strategy designed to maximise national ‘talent’ at a time of increased international competition; he also linked it with the focus on intelligence (as opposed to physical strength or mental health), which was an especially marked feature of British eugenic thought. This chapter traces the connections between eugenic thought and educational policy in the years leading up to the war, before assessing the long term implications of the 1944 Act, which many perceived to be eugenic both in intention and effect; certainly, both supporters and critics of selective education saw it as marking a significant shift in the way that the relationship between the individual and the state was configured. Political and social debates about the issue are here considered alongside a number of literary texts that shed light on the subjective and affective dimensions of upward social mobility in this period.

The 1944 Act was steered through Parliament by the progressive Conservative Education Secretary R. A. Butler but was the culmination of long-drawn-out debates over the expansion of secondary education. The process started with the Education Act of 1918, which introduced a school leaving age of 14 and required all elementary schools (the state schools attended by the overwhelming majority) to provide more advanced courses for their older pupils. The Hadow Report of 1926 recommended a break between primary and secondary education at the age of 11 and, for the first time, the division of secondary schools into three types— grammar, technical and modern. These recommendations were carried out to a limited extent, if there were sufficient local authority funds. The Spens Committee, reporting in 1938, endorsed the Hadow Report and strongly supported IQ tests as the best means of selecting children for ability at age 11. The case for selective education was further strengthened by the 1943 Norwood Report, chaired by a former headmaster of the Harrow School. This claimed, though without offering any evidence to support the claim, that there existed three ‘rough groupings’ of children who had ‘different types of mind’— those interested in learning for its own sake, those whose abilities lay in the field of applied science and those with more ‘concrete’ skills.4 Evidence was submitted to this committee by a wide range of employers and teachers’ associations, almost all of whom accepted the validity of this crude system of classification. Only the Trades Union Congress (T UC) (which represented rank and file workers), in a response to the Spens Report included in the evidence to the Norwood Committee, protested over the social implications of such a hierarchical system. Their comments are worth quoting, as they emphasise the life-long effects of educational segregation:

The separation of the three types of school is... also bound to perpetuate the classification of children into industrial as well as social strata. So long as the three types of school remain separate, it is inevitable that the Grammar School pupil will continue to look upon the black-coated job as his natural right; that the Technical High School will tend to be regarded as the training ground of foremen and of highly skilled workers in the engineering and building trades; while pupils leaving Modern Schools will have to be content with what jobs are left.5

The TUC was also virtually alone at this point in arguing for ‘multilateral’ (i.e. comprehensive) schools.

The expansion of secondary education was supported by the Labour Party on the grounds of social justice. It was widely recognised that the education of most children beyond the age of 11 was inadequate, and it was also known that more than half the working-class children selected for free places in grammar schools turned them down, as parents could not afford the loss of wages for an extra two years. Labour politicians were anxious about the generally low level of education but also felt that it was particularly unfair to condemn talented children to elementary or ‘modern’ schools. It was on this issue that their interests converged with those of eugenicists who had become concerned about the prospect of a fall in ‘national intelligence’. This question was drawn to the attention of the wider public with the publication of Raymond Cattell’s polemic The Fight for Our National Intelligence in 1937. Cattell was a psychologist whose research had been funded by the Eugenics Society, and in the first chapter of his book, he made the sensational claim that:

every clinical psychologist knows, with the conviction of 100 to 1 probability, that national intelligence is falling disastrously at the present moment through the continual rapid replacement of the constitutionally bright by innately dull and limited types.6

Cattell had worked with the pioneering educational psychologist Cyril Burt, who not only endorsed Cattell’s views about the decline in intelligence but later gave evidence on this topic to the 1949 Royal Commission on Population, estimating a future decline of about 1.5 points of IQ over each generation. Burt’s estimates had a tangible effect: the Royal Commission accepted his view and accordingly recommended the introduction of adjustments to the tax system in order to encourage the ‘educated classes’ to have more children.7

Burt was closely involved with the Eugenics Society, and his work was a central point of reference for eugenicists for more than four decades. His interest in the subject stemmed from an early connection with Francis Galton, whom he met through his country doctor father. After training in psychology and physiology, Burt began a study comparing the intelligence of boys from a preparatory school and an elementary school in Oxford and a school in the Liverpool slums. Most of the children in the first group were the sons of ‘academics, Fellows of the Royal Society, or bishops’, in other words, they came from just the kind of family on which Galton had based his arguments for ‘hereditary genius’.8 Burt, accordingly, came to the same conclusion as Galton—that intelligence was strongly inherited. He maintained this position throughout his career, to the extent of falsifying the data in papers he published in the 1950s and 1960s on intelligence in identical twins.9 His biographer L. S. Hearnshaw has suggested that these papers (which appeared after his retirement) were written at a time when Burt was feeling particularly embattled, as the tide was turning against an emphasis on heredity, and indeed against the very conception of IQ as a single, quantifiable entity.10 However, the deception was not revealed until 1974, and from the 1920s to the 1960s, Burt was a powerful figure, one of the experts on whom government could call in order to shape what Foucault would term governmental reason. He became an advisor to the Home Office, the Ministry of Health and the Board of Education, and he is cited by Greta Jones as a pre-eminent example of the ‘technicians of social engineering’ who came into their own with the expansion of social welfare during and after the Second World War.11

Through his work on IQ tests, Burt also provided an indispensable instrument of governmentality. IQ tests had first been developed by Alfred Binet at the request of the French government, in order to detect ‘mentally deficient’ children. Binet drew up a series of tests designed to measure the qualities of memory, reasoning and verbal ability, and with his colleague Théodore Simon, he developed the concept of a quantifiable mental age. In 1913, Burt was appointed to the London County Council to test for ‘defective’ children so that they could be transferred into special schools. As Muzumdar points out, although he was supposed to be testing only subnormal children, by 1915 he had set up general research into the distribution of intelligence and was refining the design of standard IQ tests.12 He was also inspired by the use of IQ tests by the US Army in 1917, in which military recruits were tested for intelligence and aptitude before being assigned to particular tasks. Seeing this as a model that could be applied to the civilian population, he began to campaign for the use of IQ tests to identify bright children from all social classes, whose intelligence, he argued, should be viewed as a national resource. In 1924, he assured the Hadow Committee that it was possible to make an accurate assessment of a child’s mental ability by the age of 12, and his support for IQ tests carried great weight with successive governments.

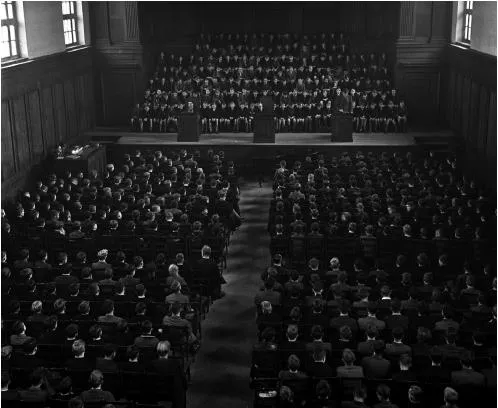

In the inter-war years debates about education were framed in terms of the competing discourses of social efficiency and social justice. The perspective of social efficiency was invoked both by those who argued that the low level of education for the poor was leading to a serious waste of national talent, and by those who took the view that as intelligence was genetically determined and already concentrated in the higher social classes, there was little point in wasting time and money seeking it out amongst the poor. The case for moving towards greater social justice through education was urged by socialists such as the historian R. H. Tawney, but only up to a point. In his Labour Party pamphlet ‘Secondary Education for All’, for example, he argued that all children should be educated to the highest possible standard, but that as individual needs and abilities varied, secondary schools should be of different types.13 The 1944 Act, which like the Beveridge Report is often seen as a touchstone of post-war optimism and egalitarianism, was inclined more towards the principle of social efficiency than social justice. It was progressive in making state education free to all and in raising the school leaving age to 15, but it was reactionary in its endorsement of the tripartite system of secondary education, through grammar, technical and modern schools. Moreover, a lack of investment in technical schools meant that the system soon became, in effect, a binary one, in which 20 –25% of the school population went to grammar and the rest to secondary modern schools (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Manchester Grammar School, 1950, morning prayer.

Figure 1.2 Bourne Secondary Modern School, Ruislip 1950, handicraft class.

LADDERS OF OPPORTUNITY

The Rise of the Meritocracy offers a scathing critique of this educational system and of the social forces that produced it. The argument is conducted through a fictional essay, supposedly written in 2033, on the May risings associated with the ‘Populist Movement’, an alliance of women and working-class men who have joined together to protest against the rigid social order of the twenty-first century. Young extrapolates from mid-twentiethcentury trends to imagine a society geared towards social efficiency, which has massively extended the selection processes developed during the two world wars. The Second World War, Young’s essayist writes, ‘woke people up to the fact that the nation possessed a supply of ability never ordinarily used to the full’; he also notes that international competition was a further spur for the introduction of competitive selection across all aspects of social and economic life.14 In this society an aristocracy of talent has replaced an aristocracy of birth, with rule ‘not so much by the people as by the cleverest people’. And as its populist critics argue, ‘intelligence’ is in this context defined solely in relation to the instrumental criteria of productivity and economic expansion. Thus:

People are judged according to the single test of how much they increase production, or the knowledge that will, directly or indirectly, lead to that consummation.... The ability to raise production, directly or indirectly, is known as ‘intelligence’: this iron measure is the judgement of society upon its members. (167–8)

In addition, Young highlights the biopolitical and eugenic effects of a move to a society in which intelligence and social status have become inextricably linked. His essayist cites Galton as the main inspiration for the new social order—his ‘Oh God, oh Galton!’ being a clear echo of Huxley’s ‘Our Ford’ in Brave New World— and frequently refers to the Fabian eugenicists Shaw and Beatrice Webb as guiding spirits. For in this dystopia the longstanding eugenicist concern with IQ has been taken to its logical conclusion. This is a society in which classes are ‘biologically’ differentiated according to merit: each of the components of merit—IQ and a propensity for effort—is thought to be quantifiable and identifiable by psychometric testing. Accordingly, the ‘talented’ are assigned to the ‘level which accords with their capacities’, so that over time the ranks of the gifted ‘have been swelled, their education shaped to their high genetic destiny’ (15). Moreover, the elite is more or less unassailable because it is legitimated by the biological ‘truth’ of genetic endowment:

Today all persons, however humble, know they have had every chance. They are tested again and again.... But if they have been labelled ‘dunce’ repeatedly they cannot any longer pretend; their image of themselves is more nearly a true, unflattering, reflection. Are they not bound to recognise that they have an inferior status— not as in the past because they were denied opportunity; but because they are inferior? (108)

Social stratification is enforced through tight regulation: IQ registers are kept at Eugenics House, and National Intelligence Cards are regularly updated. The drive to maximise ‘talent’ is supported by the campaign for ‘intelligenic marriage’ in which people are encouraged to consult the intelligence register before marrying, as meritocrats must not waste their genes. The importance of this issue is signalled through Young’s deft re-working of a familiar twentieth-century romance fiction plot, in which an aristocrat seduces a pretty working-class girl but their marriage is blocked, until it turns out—in the nick of time—that she herself is the long-lost daughter of an aristocrat. Young introduces a twenty-first-century version of this theme, in which the ‘pretty young mother’, who has been rejected with her child not because of her social status but because of her poor intelligence record, finds that ‘she is going to be all right after all, the Registry has wrongly docketed her grandfather’—he turns out to have had the high IQ rating, which is the new equivalent of noble blood, transforming her at a stroke into an acceptable marriage partner (174).

As Young makes clear, the aim of the meritocracy is not equality but ‘equality of opportunity’, or, to put it more accurately, this is the myth on which his meritocracy is founded. Like all such myths it involves paradox: the meritocracy is a society in which it is alleged (by the elite) that everyone is given a fair opportunity to find the role for which he or she is suited. Such an argument conveniently overlooks the fact that in a highly stratified society, in which ‘talent’ is identified before birth and each child assigned to an appropriate educational stream from the nursery onwards, there is no genuine equality of access to resources and support.

Young’s critique exposes a further confusion or blind spot that continued to muddy eugenic arguments. After the war even reform-minded eugenicists such as Blacker continued to invoke the principle of genetic determinism in support of their arguments for eugenic policies. For example, in his 1952 book Eugenics: Galton and After, which Blacker saw as offering a ‘reorientation’ of eugenics for a post-war society, he argues, disingenuously, that because of the complexity of the mechanisms of inheritance in man, we are justified in continuing to act on ‘the assumption whereon our ancestors who domesticated animals and plants have always acted, that like produces like’.15 Young challenged this view, his essayist drawing on the work of Hans Eysenck to argue that there can never be any certainty of the direct transmission of characteristics from parent to child: a child’s inheritance is best understood as being transmitted through rather than from its parents.16 Thus, clever parents will sometimes have less intelligent children, whom they will want, nonetheless, to have all the advantages they have had. This is one of the factors that leads the ‘new Conservatives’ in the meritocracy to make their proposal that a privileged education should be guaranteed for the children of the elite, without IQ or other testing. Th...