![]()

1 The structure of the South Korean developmental regime and its transformation

An analysis of the developmental regime of statist mobilization and authoritarian integration in the anticommunist regimentation

Hee-Yeon Cho

Preface

Before the economic crisis, the South Korean development model was a ‘successful’ model to be emulated by others. Such a conception of a successful model means that the contradictions and problems inherent in this model have not been illuminated at all. However, the crisis of the South Korean economy provided the momentum for an epistemological turning moment, which has allowed us to recognize the ‘unsuccessful’ aspects, and approach the South Korean development model as a model of crisis and contradiction.

This chapter aims to analyze the structure of the Korean development model as simultaneously a basis for rapid successful growth and its sudden crisis around the mid-1990s in the wake of the East Asian financial crisis. The chapter looks at the model’s characteristics of operation and its transformations. In this study, I explore: the structure that enabled this growth, especially political-social structure; how the same structure came to be a factor in the crisis; and in what direction the South Korean development model is currently transforming.

Characteristics of the South Korean developmental regime

Growth as a socio-political process and ‘the South Korean developmental regime’

The ‘developmental state theory’ (Johnson 1987, 1999; Amsden 1989; Evans 1995; Wade 1990; Gereffi and Wyman 1990) focused on an interventionist role for the achievement of economic growth. The developmental state theory explaining the East Asian economic miracle focuses only on the relation between the state intervention and the resulting phenomenon, that is, growth (Cho and Kim 1998: 128–132). My preference is to use the term ‘the developmental regime’ (rather than ‘the developmental state’), in order to bring to the fore the systemic and multi-faceted characteristics of the South Korean growth-oriented regime, not the phenomenal aspects of the ‘autonomous’ state intervention. I think we should not focus only on the state’s role but also see the whole structure in which more factors than the state interact.

In addition, the concept ‘regime’ is also preferred because it allows me to talk about socio-political reorganization as well as economic. Even when ‘the developmental state theory’ scholars discuss this growth, they approach it only as an economic process. In my view the growth is as much a socio-political process as it is an economic one. This is because economic growth is growth of not only the secondary industry, industrial production growth or the material production, but also socio-political reorganization of a society towards growth (Bonefeld 1987).

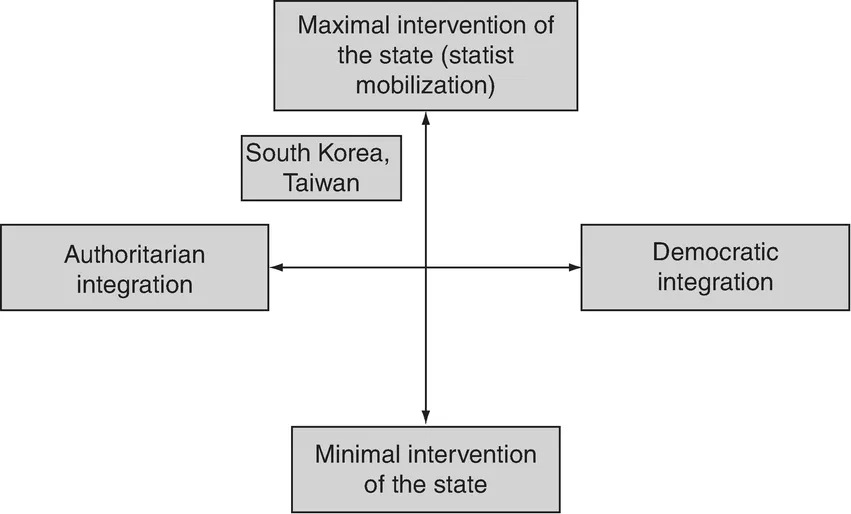

Conceiving of the growth as a socio-political reorganization includes the following two aspects. The first is the raising and distributing of material and human resources towards growth, especially in ‘resources-poor countries’ (Perkins 1994). The second is the societal integration of the members of one society towards the target of growth, that is, a kind of pro-growth integration of the working class, the popular sector and other classes. The way of raising and distributing resources is diverse from maximal intervention of the state to minimal one, while the way of the integration from very much authoritarian to very much democratic one.

Raising and distributing such resources is performed basically through the market. However, the state intervenes in this process. It is not correct to regard the state theory and market theory in East Asian development analysis as directly opposite. Rather, we can say that raising and distributing resources is performed in the interaction between the market and the state. Such interaction varies from the maximal intervention of the state to minimal one, all of which are combined with the market. Maximal intervention of the state and minimal one can be posited as poles in the same continuum, rather than the state and the market. The point is that the state’s intervention in economy is not seen as contrary to the market so the question is really whether the state’s intervention is market friendly or anti-market. For example, the state’s intervention in South Korea was market friendly: it just aimed to make business and market flourish and develop rapidly, overcoming diverse obstacles to market and business development.

In addition, we should see the difference in the way of political integration in the process of economic growth. One regime achieving a high economic growth can be democratic, however other one achieving the same growth can be authoritarian. We can characterize diverse regimes from democratic to authoritarian ones according to their political features of the developmentally oriented system.

In this sense the South Korean developmental regime, especially Park Chung-Hee’s regime, can be defined as that of maximal state intervention and authoritarian integration. This can be shown Figure 1.1. In the view of mobilization and distribution of resources, it can be defined as the regime of maximal intervention of the state, while the regime of authoritarian integration in the view of integration. I would define the maximal intervention of the state in South Korea as statist mobilization.

Figure 1.1 The mode of developmental state in South Korea and Taiwan.

The precondition of the developmental regime — the anticommunist regimented society

There has been a precondition for the developmental regime to emerge and function smoothly. I want to conceptualize such a precondition as ‘the anticommunist regimented society’. The mobilization for growth in the maximal statist form and integration in the authoritarian form has been helped by the anticommunist regimented social situation and has been made possible by utilizing and amplifying such a situation.

If social regimentation means that a certain society is regimented in a way to promote disciplinarization of social and political behavior to be accommodated to the dominant rule, factors which contribute to this social regimentation can come from many origins (e.g. Confucian culture, militaristic confrontation with foreign country, a specific historical experience, a certain ideological situation). By the concept of ‘the anticommunist regimented society’, I want to imply that such regimentation in South Korea comes mainly from societal confrontation with communism, although many other factors were involved.

The formation and reproduction of the developmental regime in South Korea can not be fully analyzed without considering interactional influences of the Cold War and the civil war. In South Korea, the intense conflict after Independence in 1945, in which social forces were polarized into left-wing and right-wing groupings, developed into the civil war. This civil war ended up dividing the Korean peninsular into a capitalist-oriented ‘right-wing’ ‘region’ and a socialist-oriented ‘left-wing’ ‘region’ (South and North Korea).

What is important in the formation of ‘the anticommunist regimented society’ is that, in the process of the violent conflicts accompanying the civil war, oppositional figures and groups were widely removed from the public arena. Actually as a result of oppression by the American Occupation Forces and the South Korea government (together with impact of the civil war), the working class movement and popular opposition movement were nearly crushed. Only progovernmental right-wing organizations could exist without the threat of death or imprisonment. Such a civil war, and the hot confrontation between them, transformed the external logic of the Cold War into an internalized consensual one, which continued to regulate social and class relations.

The internalization of the Cold War logic was helped by the popular conception that the commitment of the US had been decisive for the survival of South Korea during the Korean War. If we say that the rise of the East Asian developmental state was born out of the ‘politics of survival’ (Castells 1992), the strongest evidence can be found in South Korea. In this situation, the confrontation between South Korea and North Korea was mechanically reproduced on its own without any regard to the origins of such a confrontation. What is unique to this situation is that such self-reproduction of confrontation was internalized to become a self-censoring mechanism. This anticommunist regimented society has been reproduced easily by the fact that the Civil War was not over, but stayed in truce. That is, this characteristic of ‘society in truce’ made possible the continual domestic reproduction of Cold War-like confrontation. In contemporary histories in South Korea, this situation has been systematically fortified by the purposeful efforts of the dominant group to preserve the logic of confrontation.

In this respect, ‘the anticommunist regimented society’ in postwar South Korea can be defined as one in which the Cold War logic was, through the historical experience of the civil war, transformed into an internally consensual one and it regulated social relations and behaviors of the populace, resulting in labor discipline and popular acquiescence.

The phenomenon, which emerged in the formation of the anticommunist regimented society, is that the old landlord class was weakened so as not to block the socio-political reorganization by the developmental regime. Ironically, the confrontation between the socialist North Korea and capitalist South Korea pushed South Korea to carry out relatively progressive land reform, thus weakening the landlord class.

Although the discontent and the demands for land reform by peasants functioned as a driving force for the passing and enforcement of the land reform law in the parliament, in which assemblypersons with landlord class background occupied a majority, the land reform was forwarded by the radical North Korea land reform and an experience of revolutionary land distribution during the civil war. Land reform ‘law was passed, but not one hectare was redistributed before the North Koreans occupied the South Korea in the summer of 1950: whence came a revolutionary dispossession in all but the “Pusan perimeter” holding area’ (Cumings 1989: 12).

The ‘quite progressive’ land reform, the erosion of the material base of the landlord class and the breakdown of the former landlord class as a dominant class with effective oppositional potential against pro-bourgeoisie modernization (Lie 1991: 71) were factors that made East Asian societies go on different routes from the most Latin American societies. Because the landed oligarchies can function as potent brakes on economic growth, removal of the landlord class is an important social condition for capitalist industrialization. It is the peculiarity of the East Asian Cold War (unlike Latin America) that it contributed to land reforms, weakening the landlord class as a result. Here we can see the dual impact of the Cold War confrontation: on the one hand it contributed to opposition movements being wiped out, and, on the other hand, it led to yhe demise of the landlord class. Only under these social conditions, could the developmental regime from the 1960s become possible. And only under these conditions could statist mobilization and authoritarian integration proceed without serious threat because, in the anticommunist regimented social condition, the socio-political barrier to statist mobilization and authoritarian integration has lowered.

The formation of the anticommunist regimented society brought with it the reversion of the power in capital–labor relation in favor of the former, and the reversion of the power in state–civil society relation in favor of the former. In such an anticommunist regimented society we can see a great imbalance between both the state and civil society and between capital and labor, facilitating both statist mobilization and authoritarian integration.

In a sense, capitalism depends on the regimentation and disciplinarization of labor to fit into capitalistic order: an organization of labor in an industrial army analogous to a military army. The developmental regime from the 1960s could integrate the working class to the new capitalistic order as well as stabilize capital’s domination over the labor process by extending the existing social regimentation and disciplinarization in anticommunist regimented society to the labor process.

What is emphasized here is that the anticommunism in this period has been very hostile to North Korea. This anticommunist regimentation was like regimentation based on the ‘pseudo-wartime’ control, in particular via creating a social atmosphere of threat in the name of national security.

The statist mobilization and authoritarian integration by Park's regime

Under the condition of the anticommunist regimented society, the Korean developmental regime went on to perform the statist mobilization and authoritarian integration from the early 1960s. The statist mobilization and authoritarian integration for growth happened in the following way. First, concerning the statist mobilization of the whole society towards growth, the state intervened to support export- oriented companies and give massive support to birth of new capitals. State intervention activities, directed to constructing capital itself and valorizing constructed capital, was economic on the one hand but also political and social on the other. The state exploited all possible policy measures to support export enterprises and the accumulation of capital. For describing this kind of the state’s role, Amsden used such expression as ‘getting the prices wrong’ (Amsden 1989: 139). However, I would use such expression as ‘getting all fundamentals wrong in favor of growth and export’. As is well known, it took the form of ‘industrialization drive policy’, especially ‘export drive policy’. For this, the state intervened in the form of one-sided allocation of all economic resources towards export (e.g. allocation of credits to targeted industries and infant industries). It led the market, not merely followed it, especially through ‘industry-specific’ policies (Wade 1990: 233–236). The state actively led a strategic allocation of socio-economic resources to targeted industries and enterprises.

The statist mobilization was also done in relation to the money capital circuit. The state gave export enterprises easy access to internal savings and foreign loans. In the name of the so-called ‘export-finance’, export enterprises could receive subsidies and favors in getting bank loans easier than other enterprises. The fact that the banking system has been under the state’s control made it easier for the state to channel the stream of credit in favor of export. In addition, the state supported the enterprises, especially big enterprises and public enterprises, to borrow money in the international financial market under the guarantee of the state to back up weak credit of the enterprises. In this sense, export enterprises could enjoy privileged status in access to both domestic savings and foreign loans.

However, the statist mobilization in favor of export-oriented industrialization extended beyond economic policy to ‘getting the whole society wrong’. Here we can indicate diverse ideological interventions to inculcate social norms that fitted with incipient capital accumulation and that promoted new identities in its favor. The state has been an important agent in reproducing social norms to encourage obedience to a new order of capital. It also reproduced behaviors in favor of accumulation (e.g. savings rather than consumption). In addition, it endorsed a certain identity of the individual as a provider of low-wage labor, a production element and a provider of capital in shortage through voluntary savings. The state also promoted a new identity in the image of a self-sacrificial hard-worker in high labor intensity industries, as a self-employed worker and as a self-dependent breadwinner with self-responsibility to the individual and family security, not dependent on the state etc.

In addition, the state intervened significantly in the reproduction of a low-wage labor system. The state played an active role in keeping low-wage labor power in potential surplus and making a certain level of skill sustained, especially through legislation, e.g. new labor laws, or detrimental revisions of existing labor law.

This statist mobilization was supported by authoritarian integration. The pre-existing legal institutions (e.g. the law such as National Security Law) were crucial to the state’s intervention in reproducing a stable production system based on low-wage labor, and suppressing the opposition to such a system. Compared to the 1960s when consensus was manufactured via the modernization project, the developmental regime in the 1970s tried to integrate the labor and whole society in the more authoritarian way. The Yushin regime in the 1970s was that of harsh authoritarian integration near to totalitari...