![]()

Part I

The emergence of Holocaust research

Background and context

![]()

1 “Our Holocaust”

The public context of Holocaust research

Israeli Holocaust research did not develop in a vacuum. Its roots were not in the academic ivory tower or in a maze of archives crowded with dusty documents. Its development was closely connected to social processes within Israeli society and to the different forces vying for an influence on its Holocaust remembrance.

For this reason understanding its development is contingent on an exploration of Holocaust awareness in this society during the first decades after 1945 until the Eichmann Trial. This chapter will be dedicated to understanding the context of Israeli Holocaust research, that is, to the presence of the Holocaust in Israeli society in the years preceding independence and the first decades of statehood.

It is commonplace to see the Eichmann Trial as responsible for the drastic change in attitude towards the Holocaust and its survivors in Israeli society. This book will claim that this is far from being accurate – the Holocaust had a strong presence within Israeli society and permeated its culture and public discourse long before the trial. The trial’s impact was the result of this presence. The Holocaust’s presence in different spheres of Israeli life constitutes the background for the emergence and growth of Holocaust research.

Holocaust commemoration in the pre-state era and the foundation of the “first” Yad Vashem

In the pre-state period the Yishuv (the settlement) as the Jewish community in Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel) or Palestine called itself was engaged in a political and military struggle, aimed at establishing the Jewish state. These political and existential pursuits in the 1940s were accompanied by anger and frustration at the destruction of European Jewry and the inability of the Zionists to prevent it.

From 1942 on different suggestions were raised in the Yishuv to commemorate European Jewry and various organizations started to act in this direction. The proposals were made by individuals and public institutions as well. For example, in a letter to the editor, published in the newspaper Davar in May 1944 Jacob Böhm proposed, “that the date of the Warsaw ghetto uprising should be declared by the authorities as a holy day for our people, the anniversary for the death of our martyrs”.1 He suggested enacting specific mourning customs for that day. One year later, two weeks after the end of the war,2 in the same newspaper, Leibel Goldberg, a member of the Yagur Kibbutz, suggested publishing “a book of testimony and commemoration” with the names of Holocaust victims. The book was aimed at “taking revenge and eliminating this anonymity surrounding their death”.3 Goldberg corresponded on the subject with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi,4 Eliyahu Dobkin, and other public figures, in order to promote the publication of the book. By September 1945 Mordechai Shenhabi counted 30 (!) different proposals for the commemoration of European Jews. Individual proposals that were sent to Yishuv leaders but were left unpublished should be added to this list. One of them was by Sonia Dostrovsky, who in February 1945 proposed a “women’s project” of “institutions for homeless children in memory of Diaspora children”.5

Out of all the proposals for commemoration, the proposal of Mordechai Shenhabi was accepted by the National Council, and later on by the Zionist Congress.6

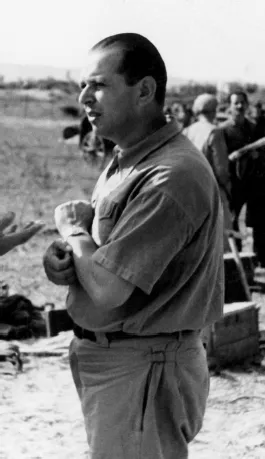

Figure 1.1 Mordechai Shenhabi, 1938. Kfar-Masaryk Kibbutz Archive.

Shenhabi was an ardent Zionist, a Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair (“Young Guard” – left Zionist movement) member, the first of the movement to arrive in Eretz Israel and a kibbutz member in Mishmar Ha-Emek. He had already submitted the first version of his proposal to the Jewish National Fund in September 1942, and during 1942–43 he was bombarding national institutions with memos and proposals on the subject. In August 1945 the idea of setting up a commemoration project was accepted by the General Zionist Council in London. Responsibility for its establishment was entrusted to a commission of the National Council headed by David Remez. The commission was soon snowed under with private proposals increasing in number as the project was getting more publicity.7

Shenhabi envisioned a monumental site with two foci – the Hall of Remembrance and the Hall of Heroism – which would commemorate Jewish fighters of World War II as well. Setting up “central archives for the history of the Diaspora, the collection of photos, pictures and documents about the destroyed Diaspora” had a secondary place in Shenhabi’s project and appeared under the heading “auxiliary projects”.8 This plan served also as a basis for the discussions towards the enactment of the Yad Vashem Law and the reestablishing of the institution in 1953 (on this more later). Despite the fact that the project had been accepted by the Zionist General Council,9 its execution was obstructed by existing Zionist organizations such as Keren Ha-Yesod (United Jewish Appeal, UJA), and the JNF, which were worried about competition in fund-raising abroad; as a result, the institution worked on “low heat” in the beginning. Problems with these organizations were solved only in 1947 and only then could serious work start at Yad Vashem.

The offices of the institution were located in a three-room apartment in Jerusalem. There were a number of employees doing office jobs and arranging archival materials collected from abroad in different ways. Dr Sarah Friedländer stood out among the employees. She was a Holocaust survivor from Bergen-Belsen, and worked at the institution as a secretary. She was born in Budapest, had the command of six languages, published articles and studies in Zionist and Jewish topics, and had organizational and administrative experience. In Yad Vashem she “laid down the foundation of the archives” and carried the load of organizing the International Conference for Holocaust Research in Jerusalem in 1947.10 The institute reached the peak of its activities with this conference that will be described at length below. An “index of communities” was also created in order to organize information for a lexicon of destroyed Jewish communities. But how does one define a community? One suggestion was to index only communities with one hundred or more Jews. This was opposed by Zerach Warhaftig (see later) who claimed that “even if there was only a single Jew” a locality should be included. Obviously, the question had its organizational and financial implications, “since copying thousands of names or numbers costs dozens of pounds”, which were not forthcoming to the institution, wrote Warhaftig to the Jewish sociologist Y. Lestchinsky.11

It should be emphasized that although Shenhabi was Yad Vashem’s originator, it was not a one-man project. Officially it was headed by an advisory board consisting of the representatives of the National Committee, the Jewish Agency, the Chief Rabbinate, the JNF, Keren ha-Yesod, the Jewish World Congress, the Hebrew University, and the Association of War Veterans.12 In effect, Yad Vashem was directed by a secretariat whose members were chosen from the advisory board. Beyond Shenhabi, the secretariat had three additional members: David Remez (he was the chairman of the National Council, the advisory board and the secretariat), Zalman Shragai (from the Mizrachi – Religious Zionist Movement and head of welfare department in the National Council), and Baruch Zuckerman (representative of the World Jewish Congress). In the beginning of 1946 after Baruch Zuckerman’s departure,13 Dr Aryeh Tartakower, head of the Jerusalem Bureau of the World Jewish Congress joined Yad Vashem Directorate, and was active in it for decades (in both states of the institution). In the beginning of 1947 Shragai was replaced by Zerach Warhaftig, also from the Mizrachi, who was instrumental in the rescue of Lithuanian yeshiva students to Shanghai during the Holocaust.14 Warhaftig was in the USA during the war, serving as the deputy president of the Poel ha-Mizrahi [labor religious Zionists] and a Board member of the World Jewish Congress. As soon as the Yad Vashem plan was published, Warhaftig voiced his firm opposition to the Shenhabi project, which in his view focused on “tombstones” while ignoring traditional Jewish ways of commemoration. According to him, the Jewish people are the people of the book, consequently “‘the book’, a Jewish expression of grief, and Jewish commemoration of the martyrs by memorial books should be in the center of the project.” In his criticism Warhaftig stressed the peripheral place allotted to the archives and the collection of documents and the lack of a book publishing budget.15

Despite his criticism of the Yad Vashem plan, Warhaftig agreed to join the institution. First he was offered the director’s post at Yad Vashem, but eventually, according to Aryeh Tartakower, he become “the representative of the National Committee in ‘Yad Vashem’, and also the representative of ‘Yad Vashem’ in the National Committee”.16 He agreed to join Yad Vashem on condition he would take charge of “documentation and archives”, which was virgin territory “least clear of all”.17 He declared that in his opinion “documentation and collection of materials should be regarded as main goal and the [building of] halls just as the physical infrastructure, but he would not set his view as being more correct”.18 Like Shragai and Remez, Warhaftig carried out his activities in Yad Vashem in the framework of his work in the National Council (he established its legal department), but unlike them, he did not consider Yad Vashem as a secondary post and divided his time equally between the two institutions. Warhaftig saw to the acquisition of materials from Jewish historical commissions in Europe, other Jewish organizations, and individuals. Right before the first Yad Vashem conference in 1947 (see later), Warhaftig formulated his views on Yad Vashem’s documentation work. “The idea of setting up the national archives of Holocaust history”, he wrote, “is a central point in the plan of the national commemoration project”:

We have set for ourselves the goal of establishing a grandiose Hall of Remembrance that would serve for concentrating and processing documents and materials concerning that period. These documents will provide for our generation and for the generations to come, the bricks and broad-stones for the construction of the history of the Holocaust, heroism and redemption in Israel. The concrete hall, the sanctuary lamp, and the field of Europe [from the monumental Shenhabi proposal – BC] will be the framework for the national memorial book.19

Warhaftig laid down two principles for the foundation of the prospective archives: “1. The all-Jewish character of the Holocaust … 2. This central archive should be located in the Land of Israel”. Warhaftig claimed that the all-Jewish character of the Holocaust determined the form of archival work because the destruction of Jewry in the different countries should be considered as one unit. Consequently, “documents about the destruction in one country constitute an inseparable part of the general material. There is no room for sectarianism and local patriotism.”20 The necessity of setting up the archives in the Land of Israel was based by Warhaftig on the claim that “the hope of re-establishing the ‘Jerusalem of Lithuania’ and the ‘Jerusalem of Slovakia’ had vanished” and after the destruction of “the large spiritual centers of European Jewry, there were no substitutes left for Heavenly and Earthly Jerusalem, for Jerusalem the holy city in the Land of Israel”.21

Warhaftig suggested

five main divisions for collected materials: 1. The scroll of tears – the story of the Holocaust history of each and every town, each and every country, 2. the scroll of martyrdom – revealing of the martyrdom of those Jewish victims, 3. the scroll of heroism – the history of the participation of the Jewish people in the war against the Nazi criminals, 4. the scroll of criminals – compiling the protocols of trials and assembling the list of criminals that have not been brought to justice, 5. the question of non Jewish relations – including Righteous Gentiles.

In addition, Warhaftig noted the need for “introspection – the impact of the events on the soul of the nation and the individual in Israel”.22 Above all, Warhaftig stressed the significance of objectivity and the scientific method. This research should employ:

the cold surgical knife of the impartial researcher, in the living flesh of our Holocaust. We should not be drawn after feelings of wrath that overwhelm us … We must not fail by exaggeration or by lack of precision in even the smallest detail.

Failure to do so will place weapons into the hands of “publicists and other penmen supporting the criminals and working on whitewashing their crimes”.23

Warhaftig had a major role in shaping the archives, but his activities in Yad Vashem came to an end with the establishment of the state and his participation in the political system as a Knesset member and minister.

Building the infrastructure of public support for the activities of the institution was a first priority in the eyes of its staff and executive during these years. Yad Vashem employees had dozens of meetings with the leaders of what they considered as their natural supporters: the Landsmanschaften (immigrant associations) in Israel and abroad. At these meetings the organizations were asked to call upon their members to record the names of the victims of their community in Yad Vashem.

In exchange for the commemoration of the individuals and the community by Yad Vashem, the respective communities and individuals were supposed to pay a registration fee, with the help of which the organizers planned to finance the activities of the institution.24 In the meantime, the members of different organizations were listed in Yad Vashem, they were to be included in a “card index” of potential supporters.25 Special effort was invested by Yad Vashem employees in getting the approval of the religi...