This is a test

- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shoko-Ken: A Late Medieval Daime Sukiya Style Japanese Tea-House

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 2003. Built in 1628 at the Koto-in temple in the precincts of Daitoku-ji monastery in Kyoto, the Shoko-ken is a late medieval daime sukiya Japanese tea-house. It is attributed to Hosokawa Tadaoki, also known as Hosokawa Sansai, an aristocrat and daimyo military leader, and a disciple and friend of Sen no Riky?. This work is an extremely thorough look at one of the few remaining tea-houses of the Momoyama era tea-masters who studied with Sen no Rikyu. The English language sources on Hosokawa Sansai and his tea-houses have been exhaustively researched. Many facts and minute observations have been brought together to give even the reader unfamiliar with Tea a sense of the presence which the tea-house still manifests.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Shoko-Ken: A Late Medieval Daime Sukiya Style Japanese Tea-House by Robin Noel Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Background to the Study

1.1 Identity & Representation

In this section the background to the study is presented. In section 1.11, the multi-faceted identity of Hosokawa Tadaoki as a tea-master, military and aristocratic figure is discussed. Following in section 1.12, the Shōkō-ken teahouse and other instances of Hosokawa Sansai’s tea architecture are presented. Finally in section 1.13, a textural resource of representative descriptions of sukiya architecture by a variety of commentators including early Europeans, modernist architects, and tea proponents are discussed.

1.11 Hosokawa Tadaoki—Hosokawa Sansai

Hosokawa Tadaoki is one of the most noted figures of the late medieval Azuchi-Momoyama and early modern Edo periods. Hosokawa is acknowledged in various capacities: as a prominent tea disciple;1 as one of the greatest military leaders of his time and one of the few figures to survive the re-unification wars during the turbulent period following the Sen Goku;2 and also for the substantial relations he held with Portuguese Jesuits.

Hosokawa Tadaoki’s interest in tea is said to have begun under the influence of his father Hosokawa Fujitaka (Yūsai; 1534-1610), and then under the greater influence of his father-in-law Akechi Mitsuhide (1528-1582).3 By the age of nineteen Hosokawa Tadaoki was already undertaking the role of ‘master of ceremony’ at tea gatherings which featured prominent guests.4 As a tea-person though, he is recognized primarily through his relationship with the great tea master Sen no Rikyū. Hosokawa Tadaoki studied tea under Sen no Rikyū, where he took the Buddhist name Sansai.6 He is also accorded as being one of Sen no Rikyū’s seven chief disciples.7 The close nature of their relationship is illustrated in a famous occasion where Hosokawa Sansai and Furuta Oribe risked themselves to bid their master Sen no Rikyū farewell at the Yodo river, following Sen no Rikyū’s confinement by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598) to house arrest in Sakai.8 Hosokawa Sansai also provided one of his own retainers to give the kaishaku, the coup de grace, at Sen no Rikyū’s ritual suicide.9 Later in life Hosokawa Sansai became patron to Sen no Rikyū’s son Dōan (1546-1607) whom he took into his service.10

Fig. 4. Chōjirō tea-bowl commisioned by Hosokawa Sansai.5 (Noble Heritage, p. 58, courtesy Eisei Bunko Museum).

Hosokawa Sansai’s tea identity is often mentioned in relation to his peer Furuta Oribe, also a daimyō tea master and disciple of Sen no Rikyū. These two tea-masters are said to represent opposites in style, manner, and even sometimes in skill. Furuta Oribe is generally regarded as the dynamic and inventive successor to Sen no Rikyū, whereas Hosokawa Sansai is noted as the orthodox, conservative and loyal follower of Sen no Rikyū’s teachings. It is Furuta Oribe who has received the most attention in tea history following Sen no Rikyū’s death, possibly due not only to his official appointment as the leading tea master, but also for his flamboyant personality and contribution to tea culture. Yet, some have also claimed that Furuta Oribe was inept at tea.11 Hosokawa Sansai has generally been overshadowed by the weight of attention paid to Furuta Oribe, and more often than not his place in tea history has been relegated to the periphery, or as is typically the case his style of tea is described as being a re-statement of Sen no Rikyū’s tea style.12 Hosokawa Sansai’s contribution to tea culture, and its significance however, should not be understated. As Nakamura Shosei states:

“Their ways of following Rikyu’s tea, however, were quite distinct. As mentioned earlier, it is said that Oribe was more liberal and that Sansai was conservative and more closely adhered to the tea of Rikyu. He did not, however, simply imitate and follow his teacher. Sansai established his own style of tea as well as his own tearooms. Although he inherited many techniques from Rikyu, there were many others that did not show Rikyu’s influence. These factors were evident and common in other warrior tea masters like Oribe. After the death of Rikyu, the world of tea developed to accept and include more of the elements common to the warrior class, and these were not characteristic of Rikyu’s tea.”13

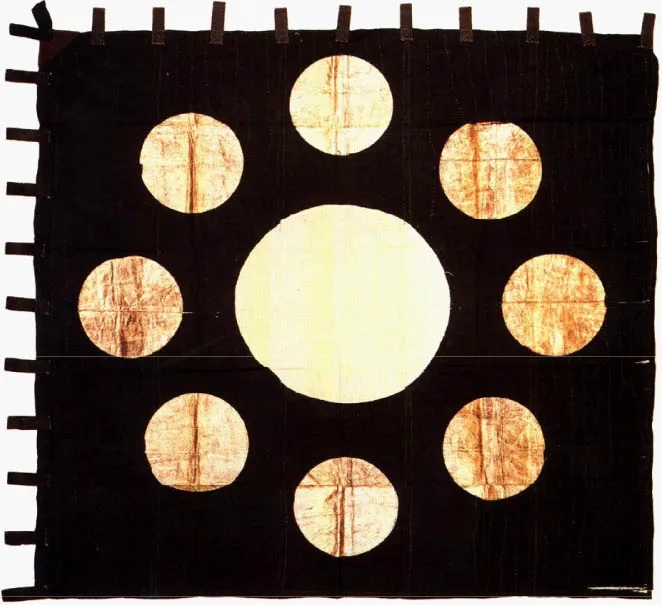

Fig. 5. Hosokawa military banner.14 (Noble Heritage, p. 76, courtesy Eisei Bunko Museum).

Hosokawa Sansai is credited with forming a school of tea under the name Ichi’o ryū.15 A tea treatise document attributed to Hosokawa Sansai, namely the Hosokawa chanoyu-no sho written in 1642 and published later in 1669, became the basis for this school and the propagation of the Hosokawa way of tea.16 This tea treatise is one of the first of its type to appear in the early Edo period, and is thought to have been aimed at young samurai tea aspirants.17 The influence of this tea treatise and other similar documents dating from this era is significant. The modern form of tea derives from these transmissions first produced by the daimyō-cha practitioners.18

As a military leader Hosokawa Tadaoki served under the banner of Toyotomi Hideyoshi during the re-unification period following the Sen Goku wars and during the ill-fated invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597.19 Following Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s death in 1598, Hosokawa Tadaoki joined the service of Ieyasu Tokugawa (1542-1616), and as a leading military figure continued to make significant contributions to the stability of the country.20 His military identity is generally seen to overshadow that of his tea life, as two famous anecdotes relate:

“In the time of the Shogun Iemitsu the Tairo Hotta Kaga-no-kami Masamori, a lord of great influence in all things, enquired through a third party whether he might see the famous possessions of the House of Hosokawa. Tadaoki gladly consented and invited him on a fixed day, and after serving his guest with a feast of the best he could provide, said: “And now I will show you my things (dogu).” And he brought out and displayed all his most valuable armour, swords and bows and arrows and such like things, but not a single tea vessel did he show. This was not at all what Masamori had expected, and he was not best pleased, but he allowed nothing of this to appear in his face, and he went away apparently delighted, after thanking his host profusely. But afterwards he again sent the third party to Tadaoki and asked him why it was that he had not brought out any of his famous tea vessels. “Oh,” said Tadaoki, “Masamori said that he wished to see my most cherished possessions (dogu), and what should this mean in a military family but the weapons and accoutrements of one’s hereditary profession?”21

“In the days of Tokugawa Iemitsu, Hosokawa Etchu-no-kami Tadaoki was the only remaining Tea Master who had received the tradition direct from Rikyu, and consequently he was much in demand as a teacher among all the daimyos who were interested in Tea. He always began his instruction with this warning: “You must remember that this is your military prowess that has obtained your fiefs and honours. Do not neglect this your main business. It may be well enough to occupy any spare time you may have with Cha-no-yu, but never let a diversion take the place of the serious work of life.”23

Fig. 6. Hosokawa Tadaoki’s suit of armour.22 (Noble Heritage, p. 66, courtesy Eisei Bunko Museum).

Hosokawa Tadaoki was recognised in the field for his restrained and pragmatic ingenuity.24 An example of this is demonstrated in the design of his suit of armour (fig. 6), which he devised as a means of protection from musket shot. In this design, which was later widely copied, we can appreciate Hosokawa Tadaoki’s preference for lack of adornment and utilitarian style.

Hosokawa’s artistic abilities elsewhere are also noted (refer fig. 7):

“It is unusual to find the head of an important family, like Hosokawa Tadaoki, turning his hand to lacquerware. While a daimyō was expected to devote himself to some cultural pursuit, he normally left the craftsmanship to others. He might admire a tea bowl, but it was beneath his station to master a potter’s wheel. Few crafts, more-over, are as painstaking and difficult as lacquerware. Properly curing and shaping the base, as well as applying, polishing, and reapplying the layers of resin, are skills that take years to learn. Tadaoki’s gift as an artist, however, were more than matched by an affinity for the hands-on, practical business of life. He could create an exquisite work like this flask; he could also teach stonecutters how to shape the blocks for the facing of a castle moat.”25

The Hosokawa house originated from Miyazu in the province of Tango.26 Since the ear...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1.0 Background to the study

- 2.0 Internal Architecture

- 3.0 External Architecture

- 4.0 Inner Garden

- 5.0 Outer Garden

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index