![]()

Part

I

DEICTIC THEORY

![]()

Chapter

1

NARRATIVE COMPREHENSION AND THE ROLE OF DEICTIC SHIFT THEORY

Erwin M. Segal

State University of New York at Buffalo

This book represents the collaborative work of a group of students and faculty at the State University of New York at Buffalo. We have our homes in various disciplines, including communicative disorders, computer science, education, English, geography, linguistics, philosophy, and psychology, but most of us think of ourselves as practicing cognitive scientists. As cognitive scientists, we are able to consider a far larger set of concepts and methods than are normally available within each of the individual disciplines. Moreover, by seriously interacting with one another on a regular basis, we attempt to keep our ideas coherent with positive inputs from all of the disciplines.

The idea of cognitive science is one that is beginning to have greater favor within the walls of academe. The path to truth is not defined by a single discipline nor by a single methodology. Cognitive science takes its topic—cognition—and tries to understand it from a variety of knowledge bases and basic methodologies.

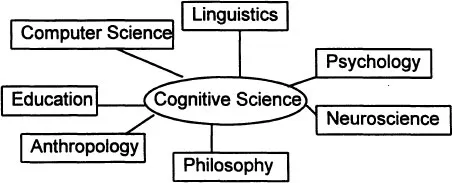

As illustrated in Fig. 1.1, we assume that different disciplines, using different methods, have each developed an accepted database or shared set of beliefs which can contribute to the understanding of cognition. The science of cognition is informed by all of the disciplines. Cognitive scientists presume that two pieces of information must be consistent with each other if they are to be considered valid. The researchers in cognitive science have the task of using knowledge from each of the disciplines to help sharpen and clarify the claims of the others. Conceptual inconsistencies across methodologies or disciplines are viewed by cognitive scientists as problems to be solved. The output of such an approach should be a solid database and a theory that is conceptually coherent with the best of each of the separate disciplines.

Fig. 1.1. Some of the disciplines that supply concepts and methods to the field of cognitive science.

The research represented in this book is focused on the process of interpretation of narrative text and the mental representation that might result from this process. We do not directly investigate perceptual or motor processes or the differences between oral and written text. Therefore, unless otherwise specified, telling, writing, hearing and reading, all refer to language activity generalized across modality.

The ultimate goals of our research program include (a) identifying the knowledge that a reader must bring to a text in order to understand it, and (b) that a writer must have brought to a text in order to have produced it, (c) describing the abstract structure of the knowledge needed for (a) and (b), (d) characterizing the processes by which a representation in memory is modified as a text is being read, and (e) by which a representation in memory is accessed as a text is being produced, (f) describing the new representations, (g) constructing a (computational) model of this process and representation, and (h) showing that the model understands the text by having it pass a Turing test by answering questions about it.

In addition to having the above goals, some of us are concerned with other questions concerning narrative. What is a story? Why are some stories or storytellers “better” than others? What does one gain by reading, viewing, or listening to a story? Why do people tell stories? Why do they listen to them? Why are these popular activities in virtually all cultures?

This anthology represents some of the work we have done so far. Much of this work has been in the development and articulation of the process by which certain information representing the spatial, temporal, and character structure implicit in the narrative is produced and understood.

In this chapter, we review some ideas relating to discourse comprehension and production and narrative interpretation that have influenced our research. We then present a brief overview of Deictic Shift Theory, which underlies the research of most of the contributors to this volume.

Approaches to Narrative Comprehension and Production

Different researchers, theories, and disciplines emphasize different aspects of cognition and communication, and thus explicitly or implicitly impose different sets of constraints on how narrative comprehension and production is to be understood. In this section some of these different approaches are described. We learn from and are influenced by each of them.

Communication Theory

Communication theory originated in an analysis of communication from the perspective of people sending and receiving messages over communication systems such as telegraph and radio (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). Such physical systems support the conduit metaphor, which is a popular metaphor for communication and language comprehension (Reddy, 1979). This view holds that a message is transported from a sender to a receiver within the symbols of the communication system. The metaphor is quite explicit in general language use— “He delivered the message to me” “I acted upon the message as soon as I received it”—and is implicit in several language and narrative theories.

In some sense, the mathematical theory of communication (Shannon & Weaver, 1949) formalizes the conduit metaphor. It is designed to evaluate the success of the transfer of a message from the source (e.g., speaker) to a destination (e.g., hearer). The theory emphasizes the properties of the code. We learn from communication theory that a communication system such as language contains a small number of basic elements (e.g., phonemes), and that these are combined to produce larger more meaningful elements (e.g., words). Still larger units of communication are possible, but are not usually studied. By implication, the message to be communicated is hidden within the coded message. The speaker sends a message by encoding it into transmittable units, and the hearer understands the message by decoding the coded sequence of units received. Communication may fail if some of the codified elements get distorted in transit or there are encoding or decoding errors. Certain, but not all, interpretations of classic communication theory (Shannon & Weaver, 1949) are consistent with the conduit metaphor. Those interpretations argue that in order to communicate, the source starts with an identifiable unit of information to be communicated (a message), puts it into a form in which it can travel, and sends it toward its destination. When the encoded message arrives at the destination, it can be decoded —that is, put back into its original form.

Meaning Extraction Theories

Meaning extraction theories focus on the structure of the language rather than on the communication process, but the implicit constraints of the conduit metaphor remain. Communication theory relies heavily on the mathematics of probability applied to the likelihood that linguistic units will succeed one another. The formal and computational linguists who presume a meaning extraction theory agree that ideas are expressed by sequences of units, but in order to produce or understand a text, a language user must apply a sequence of syntactic and semantic rules to the idea to be communicated or to the presented text. This process goes far beyond decoding and concatenating a string of elements.

It became clear many years ago (Katz & Fodor, 1963; Lashley, 1951) that concatenations of word meanings alone cannot explain comprehension. One needs to recognize the specific relationships among meanings. “Man bites dog” does not mean the same thing as “dog bites man.” Although the tasks of comprehension and production became much more complicated with the addition of complex syntactic rules marking the semantic relations, the major premise of the conduit metaphor remained unsullied. Language still works because writers write sentences which contain meanings, and readers understand text by unpacking the meanings contained in the sentences.

Meaning extraction theories, which require a literal linguistic approach to comprehension, have been implied or held by many researchers (Chomsky, 1965; Davidson, 1967; Fodor, 1975, 1983; Pinker, 1984). They presume that language is a very complicated system. In order to be able to speak and understand linguistic utterances, one must know the rules of the language. Rules are manifested in implicit structural relations between elements within sentences, and these rules must be known by both speaker and hearer. Thus, problems such as, “What has to be known in order to comprehend the sentences of a language?” and, “How is the knowledge of that language acquired?” are important to study. This approach, which underlies the study of generative grammar, has some very important theoretical constraints, including the presumption that the first stages of language processing are dependent solely upon formal properties of the language, and are strongly circumscribed. Thus, language researchers can confine their study to properties of the linguistic system. They do not have to deal with general knowledge, nor the physical, social, and intentional context of utterances.

One difficulty that these theories face is the complexity of some of the proposed rules. Linguistic rules, which are needed to uncover the meaning conveyed by the text often seem so complex that their leamability is doubted. If rules necessary for comprehension and production are too complex to be learned, they must be innately given. Many linguists lean toward nativism because of such problems (Chomsky, 1965; Pinker, 1984), because regardless of the complexity of the rules, they hold that whatever meaning a sentence contains must reside within it, and the meaning must be recoverable by a competent hearer.

In meaning extraction theories, the comprehension process requires parsing the incoming sentences using lexical and syntactic information, retrieving the appropriate lexical meanings, identifying the logical relations among them, and building the semantic structure(s) implicit in the sequence of sentences. These tasks may be difficult or even impossible to learn, but they clearly constrain the domain of analysis. Comprehension is a linguistic problem; it does not require knowing where the sentence was said, who said it, what knowledge the hearer has about the subject, nor why the speaker said what he or she did. Production can also be seen as a linguistic problem; one starts with the semantic representation of a sentence to be communicated. By successive transduction of forms from the original idea unit (probably stored as a semantic representation), to its lexical and syntactic representations, to its phonological and phonetic representations, the speaker gradually converts the idea to a form that can be spoken. From a meaning extraction theory perspective, language comprehension and production take place in an encapsulated linguistic module in the brain that receives an input of linguistic strings and produces as output their conveyed meanings (Chomsky, 1965; Fodor, 1983).

Meaning extraction theories presume the conduit metaphor. The meanings of the messages are contained in the linguistic strings. When interlocutors communicate, they send each other messages encrypted within the uttered sentences. Receivers of messages must use their powerful decoding apparatuses, that is, knowledge of the language, to recover the meanings of the sentences received.

Theories of Structured Representation

Most of the research and analyses done by proponents of meaning extraction theories focused on the analysis of linguistic units, usually no larger than single sentences. Their analyses tended to be of the sentences considered in isolation and out of context. In the 1960s, after a period of several decades during which it was neglected, empirical scientists again began to study narrative and discourse (Freedle, 1977, 1979; Pompi & Lachman, 1967). It did not take researchers long to realize that the syntax and semantics of expressed sentences do not contain all of the information that is conveyed. Much of what is needed to understand a text has to come from elsewhere. There was a growing amount of empirical evidence to support such a claim. A great deal of information not directly contained in a text is often implied by it (Brewer, 1977; Pompi & Lachman, 1967; Schank & Abelson, 1977), and text often cannot be understood if taken out of context (Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Dooling & Lachman, 1971).

Meaning extraction theorists could argue that one must separate the comprehension process from what is concluded from the text. Other researchers, however, argued that comprehension cannot be separated from interpretation (Minsky, 1981; Rumelhart, 1975; Schank & Abelson, 1977). Whatever the explanation, much of the information necessary to understand the event or situation under discussion is often missing in the sentences of the text. Consider, for example, the following sentence: “Smith hit a sharp grounder to short, but he was so fast that he beat Miller’s throw by two steps.” Important issues concerning the mechanisms and processes of comprehension are, “What is necessary for understanding this passage?” and, “When is it understood?”

One understands the previous example only after activating a memorial structure containing knowledge about baseba...