![]()

1

Introduction

Malaria is a major problem in many parts of Asia, Africa, and central and South America. Malaria occurs in about 100 countries. Approximately 40 per cent of the world’s population is at risk of contracting malaria. The outlook for malaria control is grim. The disease, caused by mosquito-borne parasites, is present in 102 countries and is responsible for over 100 million clinical cases and about 2 million deaths each year. Over the past two decades, efforts to control malaria have met with less and less success. In many regions where malaria transmission had been almost eliminated, the disease has made a comeback, sometimes surpassing earlier recorded levels. The dream of completely eliminating malaria from many parts of the world, pursued with vigour during the 1950s and 1960s, has gradually faded. Few believe today that a global eradication of malaria will be possible in the foreseeable future.

Box 1.1: Global Statistics on Malaria

• Malaria is one of the planet’s deadliest diseases and one of the leading causes of sickness and death in the developing world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 300 to 500 million clinical cases of malaria each year resulting in 1.5 to 2.7 million deaths.

• Children aged one to four are the most vulnerable to infection and death. Malaria is responsible for as many as half the deaths of African children under the age of five. The disease kills more than one million children — 2,800 per day — each year in Africa alone. In regions of intense transmission, 40 per cent of toddlers may die of acute malaria.

• About 40 per cent of the world’s population — about two billion people — is at risk in about 90 countries and territories. 80–90 per cent of malaria deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa where 90 per cent of the infected people live.

• Sub-Saharan Africa is the region with the highest malaria infection rate. Here alone, the disease kills at least 1 million people each year. According to some estimates, 275 million out of a total of 530 million people have malaria parasites in their blood, although they may not develop symptoms.

• Of the four human malaria strains, Plasmodium falciparum is the most common and deadly form. It is responsible for about 95 per cent of malaria deaths worldwide and has a mortality rate of 1–3 per cent.

• In the early 1960s, only 10 per cent the world’s population was at risk of contracting malaria. This rose to 40 per cent as mosquitoes developed resistance to pesticides and malaria parasites developed resistance to treatment drugs. Malaria is now spreading to areas previously free of the disease.

• Malaria kills 8,000 Brazilians yearly — more than AIDS and cholera combined.

• There were 483 reported cases of malaria in Canada in 1993, according to Health Canada, and approximately 431 in 1994. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA received reports of 910 cases of malaria in 1992 and seven of those cases were acquired there. In 1970, reported malaria cases in the USA were 4,247, with more than 4,000 of the total being US military personnel.

• According to material from Third World Network Features, in Africa alone, direct and indirect costs of malaria amounted to US $800 million in 1987 and are expected to reach US $1.8 billion annually by 1995.

I

Malaria in India

In India, the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) was launched in April 1953. Its core was the Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) with DDT (1 gm per sq. metre of surface area) twice a year in endemic areas where spleen rates were over 10 per cent. The NMCP was in operation for five years (1953–58). Its results were highly successful, in that the incidence of malaria declined sharply from 75 million cases in 1953 to 2 million cases in 1958, an estimated 80 per cent reduction of the malaria problem. Encouraged by these spectacular achievements in India, the WHO had recommended ‘malaria eradication’ as an international objective in 1955. The objective of the programme was reduction of the parasite reservoir in the human population to such a negligible degree that there would be no danger of resumption of local transmission.

The Indian campaign was considered to be the largest public health endeavour in the world, and contributed much towards the global effort of malaria eradication. The National Malaria Eradication Programme (NMEP) progressed satisfactorily and the incidence of malaria was brought down to merely 0.1 million in 1965 with complete elimination of deaths due to malaria. However, the NMEP suffered a setback from 1965 onwards due to several reasons. The most decisive was the short supply and late arrival of imported DDT due to unavoidable reasons (Pattanayak et al. 1994).

The rising trend of malaria was facilitated by developments in various sectors to improve the national economy under successive five-year plans. Malaria, at one time a rural disease, diversified into various ecotypes under the pressure of development — forest malaria, urban malaria, rural malaria, industrial malaria, border malaria, and migration malaria, the last cutting across boundaries of various epidemiological types.

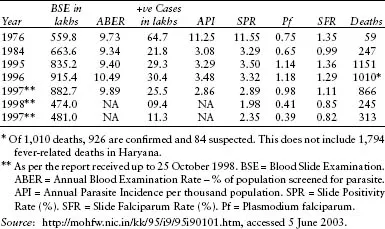

Accepting the recommendations of the Consultative Committee of Experts (1974), the Government of India embarked on a Modified Plan of Operation (MPO) for NMEP in 1976. With the implementation of the MPO, the total number of malaria cases came down from 6.47 million in 1976 to 2.18 million in 1984. Since then, the number of cases has been contained to around 2 million annually. Table 1.1 gives an idea of the changing incidence of malaria in India for the period 1976–1997.

Table 1.1: Changing Incidence of Malaria in India

Further, malaria returned in the 1990s with new features not witnessed during the pre-eradication days: vector resistance to insecticides; pronounced exophilic vector behaviour; extensive vector breeding grounds, created principally by water resource development projects; urbanization and industrialization; change in parasite formula in favour of P. falciparum; resistance in P. falciparum to Chloroquine and other anti-malarial drugs; and human resistance to chemical control of vectors. Malaria control has thus become a complex exercise.

Till 25 October 1998, a total of 937,536 malaria cases, including 405,210 falciparum cases, were reported from the various states. Malaria incidence declined by 17.05 per cent compared to 1,130,291 malaria cases of 1997. The Pf proportion, however, increased from 34.82 to 43.22 per cent. While malaria cases increased in Goa, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa, they declined in the rest of the states (NHP 2001).

Taking into consideration the variations among states, the central government’s assistance, amounting to Rs 130.99 crore, was made available to states in 1998–99. This included 100 per cent cash assistance to the north-eastern states under the NMEP. Under the World Bank project, assistance amounting to Rs 129 crore was earmarked to seven states (Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Orissa) and to other states in case of need, including cash assistance to District Malaria Control Societies (DMCS).

National Strategies to Eradicate Malaria

The National Malaria Control Policy (NMCP) operates under the National Vector-Borne Disease Control Programme in five-year strategic plans (current plan 2002–2007) and coordinates strategic decisions with the National Technical Advisory Committee on Malaria and with state health authorities. The National Health Policy of 2002 reinforced the commitment to malaria control, and set as goals the reduction of malaria mortality by 50 per cent by 2010 and the efficient control of malaria morbidity. Malaria control in India relies heavily on active case detection: every year nearly 100 million blood smears are taken from fever cases identified in the home, and patients are treated promptly if diagnosis of malaria is confirmed. Access to prompt diagnosis and treatment and education is further provided through village health workers, drug distribution depots, and fever treatment depots. In selected areas, there is targeted vector control through IRS, and larvicides.

Box 1.2: National Malaria Policy & Strategy Environment

Malaria Strategy Overview for 2003 | Strategy |

• Treatment and diagnosis guidelines: | Yes |

– published/updated in: | 2001 |

• Monitoring anti-malarial drug resistance: | Yes |

– number of sites currently active: | 13 |

• Home-based management of malaria: | NA |

• Vector control using insecticides: | Yes |

• Monitoring insecticide resistance: | Yes |

– number of sites currently active: | 72 |

• Insecticide-treated mosquito nets: | Yes |

• Intermittent preventive treatment: | NA |

• Epidemic preparedness: | Yes |

Anti-malarial Drug Policy, End 2004 | Current Policy |

• Uncomplicated malaria: | |

– P. Falciparum | CQ |

(unconfirmed): | ASU(3d)+SP (5 provinces) |

– P. falciparum | CQ+PQ |

(laboratory confirmed): | ASU(3d)+SP (5 provinces) |

– P. vivax | CQ+PQ |

• Treatment failure: | SP |

• Severe malaria: | Q(7d) |

• Pregnancy: | |

– Prevention | CQ |

– Treatment | CQ |

Source: www.mrcindia.org. Accessed 7 October 2008.

Malaria is currently somewhat under control in vast areas of India, covering almost 80 per cent of the population, despite increasing population density and aggregation, rapid and unplanned urbanization, and increased migration. However, developmental activities, expansion of agriculture, and deforestation have the potential for increasing anopheline mosquitoes’ breeding sites. A survey in Orissa in 2003 demonstrated coverage with the drug distribution depots and fever treatment depots of 98.7 per cent of the villages. About half of the fever cases sought treatment at the drug distribution depots and fever treatment depots, about 36 per cent from a health worker or primary health centre, and only about 13 per cent from other sources such as private medical practitioners. This represents a considerable increase in the proportion of people with fever seeking treatment from government sources compared with observations in the National Sample Survey in 1995–96. Following the 1995–96 malaria outbreak, Maharashtra introduced intensified active surveillance, prompt radical treatment, selective IRS with pyrethroids and larviciding in high-risk areas. ITNs (Insecticide-treated Nets) were distributed in areas of medium transmission. Under the Ministry of Health’s (MoH’s) Enhanced Malaria Control Project, which aims to control malaria in eight states including Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, where malaria morbidity dropped in the project’s districts by 46 per cent compared with 1997. Before 2004, approximately 1.8 million ITNs had been distributed and an additional 3.8 million ITNs are being procured. Over the same period, the population covered by the IRS decreased by more than 50 per cent.

The Ministry of Finance allocated funds to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare for the various national health programmes, including malaria, a portion of which was released to state governments. Over US$ 49 million was allocated to malaria control from the MoH in 2003. In addition, many states allocated significant budgets for malaria control activities from state resources. The World Bank has supported the Enhanced Malaria Control Project since 1997, disbursing approximately US$ 140 million; however, the project was expected to close in October 2005. Starting in 2005, the GFATM will provide an additional US$ 30 million for malaria control activities for two years in states that are not covered by the Enhanced Malaria Control Project, primarily those in the north-eastern part of the country. In addition, the Government of India has requested funding from the World Bank for a Vector Borne Disease Control Project that was due to begin mid-2006 and was expected to significantly expand the number of states covered. Gujarat is one of the beneficiary states for different schemes to eradicate malaria as a part of national agenda.

II

Malaria in Gujarat

Gujarat became a separate state in 1960 after the reorganization of Bombay state. According to the 2001 census, its total population is 50.6 million, divided into 26 districts. Gujarat is considered one of the endemic states for malaria in the country. It is one of the highly malarious states in India, with Surat district responsible for the maximum number of malaria cases among all districts of the state. Gujarat is endemic for malaria, dengue, and Japanese encephalitis — all mosquito-borne diseases. Table 1.2 shows the prevalence of malaria in Gujarat for the period 1999–2003. Cases of malaria increased in Gujarat from 64,130 in 1999 to 130,734 in 2003 (104 per cent rise). Falciparum cases also increased from 10,617 in 1999 to 30,890 in 2003 (191 per cent rise). Annual parasite incidences per thousand population also increased from 1.36 per cent in 1999 to 2.48 per cent in 2003.

Environmental conditions of Gujarat help determine the intensity of malaria transmission. The optimal climate for parasite development in the mosquito is a temperature of between 30°C and 40°C with humidity in excess of 60 per cent. Development from egg to adult may occur in seven days at 31°C, but takes about 20 days at 20°C.

Rainfall patterns help in the prevalence of malaria in Gujarat as mosquitoes benefit from rainfall. Even large amounts of rain that flush away mosquito larvae can produce pools of water that serve as future larval development sites. In areas of unstable malaria transmission, such conditions often bring about an explosion of anopheline mosquitoes and frequently contribute to epidemics.

Human intervention in the environment can create larval development sites and ‘man-made’ malaria. For example, massive logging during monsoon results in a proliferation in certain areas of sunlit pools of water, an ideal habitat for mosquitoes. Road building and other types of infrastructure projects, as well as agriculture and irrigation, are among a number of human activities that can s...