1

The Obersalzberg

There was a time when archaeology, as a discipline devoted to silent monuments, inert traces, objects without context, and things left by the past, aspired to the condition of history … in our time history aspires to the condition of archaeology, to the intrinsic description of the monument.

—Michel Foucault

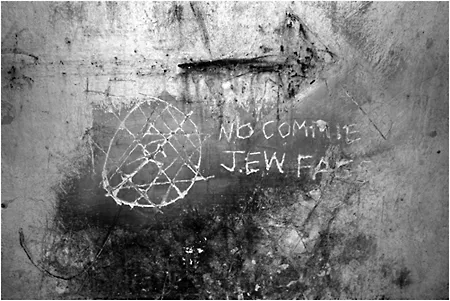

While strolling amid the awesome beauty of the Obersalzberg, just above the Bavarian town of Berchtesgaden, it utterly chills to realize that the dank, mossy, overgrown ruins embedded in the landscape are remnants of the places where Hitler vacationed, entertained world dignitaries, and held meetings of strategic and military importance. Incongruously abutting this melancholy landscape, a huge, new, unbelievably shiny, glass and steel, horseshoe-shaped, five-star InterContinental Hotel shimmers. A pleasure palace for well-heeled tourists now mingles with the former site of an important Nazi holiday spot, Hitler’s Berghof, which came to be widely understood as the Nazi spiritual home. But this complicated landscape, drenched with memory-catalyzing objects testifying to the huge complex that once dominated the mountain, shields a vast bunker system that lies below it. The moist and dewy tunnels where water dribbles down the walls offer a remarkable testament at once to the failure of the Nazi project and to the endurance of neo-Nazis who have stenciled the walls extensively. While the aboveground topography witnesses a battle between memory and forgetting, the bunker system stubbornly works toward remembrance—although often not of the victims but rather of the perpetrators. For below the beautiful mountain, swastikas, anti-Semitic, and anti-queer slogans still proliferate; on the walls, in English, one finds “No Commie Jew Fags.”

What do we make of this place? What does it say about our early twenty-first century moment that we can vacation where Hitler did? How do we understand the memories that spaces hold? Studying the rise of a luxury hotel on this beautiful, troubled mountain allows us to reflect not only on the curiosities of this particular site, but also on larger questions about how the ghosts of the past inhabit the present. The Obersalzberg has gone from a place where Freud enjoyed gathering mushrooms, to a place where Hitler and many other high-ranking Nazis vacationed and plotted, to a U.S. Army recreation center, to a luxury resort. In what follows I examine what it means to say that the land is, to use Margaret Olin’s words, “tainted

ground” (3). While Part One, “Burning Landscapes,” focuses on a particular Nazi site, this discussion of the transformation of spaces with difficult histories is applicable to other situations. Those concerned with ground zero—the site of the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack in New York— struggle with how to incorporate a history of violence and the memory of the victims into the new form of that particular place. And, of course, there are sites all over the world where brutal events occurred, from private scenes of domestic violence to the killing fields of Cambodia, from the massacres in Armenia to the bombings in Afghanistan. As Kenneth Foote details in Shadowed Ground, landscapes and spaces of violence are treated very differently depending on the choices of the communities or families affected. In some cases a need arises to eradicate the site of violence, in other cases to preserve it as a memorial, and in others to reintegrate the site back into the “normal” landscape of daily life. The Obersalzberg was not a scene of violence, it was not a concentration camp; it was an immensely important strategic and propagandistic Nazi site. To be sure, the beautiful landscape unwittingly supported a violent regime. But unlike concentration camps that have become memorials and unlike daily spaces of violence that meet diverse ends, memories of the Nazi time on the Obersalzberg have to account precisely for this curious absence of violence in the very space where one of the world’s most violent regimes plotted and imagined a world shaped by eradication. “Burning Landscapes” outlines some of the fascinating history of the Obersalzberg, analyzes Sybille Knauss’s novel Eva’s Cousin (2000), looks at some curious photo albums, and finally examine the lavish Hotel InterContinental built in 2005.

In November 1938 the British magazine Homes & Gardens featured a gushing article detailing the delights of Hitler’s holiday chalet on the Obersalzberg. “The site commands the fairest view in all Europe,” the starry-eyed author and photographer, Ignatius Phayre, noted. “The curtains are of printed linen, or fine damask in the softer shades. The Führer is his own decorator, designer and furnisher, as well as architect” (194). The article goes on to describe the “delightful” and “lovely” daily routine maintained by Hitler on the Obersalzberg. Granted, when the article went to press Kristallnacht (9 November 1938) had not yet happened, World War II had not yet exploded, and what we now know as the Holocaust had not yet accelerated. Nonetheless, in the first five years of the Hitler dictatorship, the local and international press was full of accounts of Nazi violence so no one could legitimately claim, as the peaceful images of the Berghof suggest, that the Nazi regime would become a pacific force in Europe.1 That Homes & Gardens would have made the choice to fawn over Hitler and his chalet so conspicuously seems to our early twenty-first century consciousnesses, incredible, immoral, ridiculous. Yet the kinds of photographs that accompany the article formed a crucial aspect of the Nazi propaganda machine because the idealization of the Obersalzberg became a linchpin in the Nazi plan to rationalize the war; if we only struggle through, Nazi propaganda maintained, we can all bask in Bavarian folk culture. “Frauen Goebbels and Göring,” Phayre discovered, “in dainty Bavarian dress, arrange dances and folk songs” (195). Thus the Homes & Gardens essay paints the Obersalzberg as a folksy mountain trading on Bavarian nostalgia and Nazi kitsch that can willfully ignore the violence that had always been an inherent part of the Nazi regime; this kind of nostalgia bolstered Hitler’s coupling of the city as a degenerate, Jewish space and allowed the regime to oppose the “danger” of the cosmopolitan influence with the supposed simplicity of mountain folklife.2 The Obersalzberg is a site of beauty and cleanliness that lies at the heart of the Hitler cult.

Timothy Ryback notes that Hitler “chose this mountain in the Bavarian Alps for conceiving and engineering many of his most momentous acts of governance” (Hitler’s Private Library 152). The Obersalzberg is almost always represented, in the view of an American soldier portrayed in the film Band of Brothers (which details the 101st airborne division’s victorious arrival at the Eagle’s Nest) as the Nazi spiritual home.3 This enduring image of the Nazi spiritual home stems from several factors: Hitler’s attraction to the area was heightened by the proximity of the Untersberg, a mountain that, as the brothers Grimm document, is legendary for its association with mighty but sleeping kings whose awakening will herald an Armageddon that will in turn usher in a new Golden Era. Hitler, who was intensely attracted to German legends, saw himself as such a king and made sure that the famous panoramic window of the Berghof faced the Untersberg. As Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s foremost photographer, remembered, “the most wonderful thing of all was the superlative view from the windows of the wild massif of the Untersberg, in which, according to legend, the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa had taken up his abode” (Hitler Was My Friend 185). In addition, because the area was fenced off after 1937 and was thus only accessible to important Nazis and their guests, the Nazi complex itself took on a mysterious, mythical quality. The contemporary press was full of speculation about the Führer’s activities on the mountain, and toward the end of the war the Allies believed that Hitler was building a vast “Alpine Fortress” from which he intended to make his last stand. From 1936 onwards the Obersalzberg was also the place where Eva Braun, Hitler’s supposedly secret mistress, was primarily living. The rumors circulating around Braun contributed to the mythical quality of the mountain and are extensively explored in Eva’s Cousin (see Chapter 2). These and many other mysteries surrounding the mountain have made the Obersalzberg a rich source for artistic imaginings about the Nazi spiritual home. Among the texts set on the mountain are Aleksandr Sokurov’s interesting film Moloch (1999), Harry Mulisch’s Dutch novel Siegfried (2001), and a passing reference in John Banville’s novel Shroud (2002).

The Obersalzberg complex was important in furthering the Nazi insistence on a premodern (and, in the context of the Weimar era, a premodernist) image of “simplicity.” Yet the dark complexity of the initial incarceration of thousands of communists, the assault on the church, the devastating murders of the mentally and physically handicapped, the slaughter of thousands of Poles, the execution or incarceration of thousands of critics of the Nazi regime, and of course the genocide of homosexuals, gypsies, and millions of Jews, all of which was achieved in the name of fiercely defending this premodern “simplicity,” was masked by Nazi propaganda executed on the Obersalzberg. While some of these propagandistic images featured scenes of the Nazi inner court engaged in intense, world-transforming deliberations, the majority featured the ultimately false representation of the Berghof as a space of connection with the people and as the one place where Hitler could be human. The dual, modern/antimodern nature of the Nazi project finds its perfect representation in the dual bunker-to-hotel structure of the Obersalzberg. No doubt the Obersalzberg, its history, and the many photographic, filmic, or novelistic texts it has inspired fascinate; but every fascinated person with this area is not by a long stretch a neo-Nazi. As early as 1955 Obersalzberg historians such as Josef Geiss, whose work I cite extensively here, found themselves defensive about their fascinations with the Obersalzberg. Geiss, who reissued his history of the Obersalzberg multiple times, was taken to task for what some perceived to be his Hitlerian bent. In the 1972 reissue of his 1955 history of the Obersalzberg, Geiss asks: “Who really thinks that all those visitors only come to the Obersalzberg to feel some of Hitler’s and Eva Braun’s spirit? This would mean that the many U.S. generals, the high foreign politicians, and even many German ministers of our time could be accused of the same intents” (23). Geiss criticizes Nazism and remains supremely nostalgic for the time before the Third Reich, the time of Mauritia Meyer and the Pension Moritz when “simple” country living combined with artistic sensibilities. Geiss describes the arrival of the fascists thusly: “Green meadows and forests became ugly sites of construction. Pretty country- and boarding houses were torn down and modern stone buildings were erected. Instead of peace-loving and solitude seeking resort guests only politicians, people in party-uniforms, and horrible fanatics arrived” (65).

As these comments indicate, the Obersalzberg presents an interesting case for the endless debates about the modernity of Nazism; some scholars argue that, because the Nazi regime relied heavily on modern propaganda techniques and advanced military technology, because it perfected the technology of genocide by creating killing centers, Nazis should be considered as quintessentially modern (see Bauman). Other scholars argue, on the other hand, that the profound emotional ties binding Hitler to the masses depended upon his ability to project himself as a “man of the people” who would restore German greatness by mining the greatness of the past. Hitler constantly compared himself to Frederick the Great (1712–1786) and Goebbels gave Hitler the gift of Carlyle’s multivolume biography of Frederick in the bunker; at the very end of the war, Goebbels “read Carlyle’s Frederick the Great to comfort his leader, and not without effect” (Miskolczy 130).4 Hitler also relished self-aggrandizing comparisons to Bismarck, Napoleon, and others, and he constantly evoked Teutonic myths of sleeping kings ready to reawaken at the right historical moment. The image Hitler projected from the Berghof was distinctly premodern; a man of nature, sometimes in lederhosen, caballing with the animals. Yet below the Obersalzberg complex, as the war raged on and the tide was turning against Germany, Hitler ordered a huge bunker system to be created deep within the mountain. One of the Obersalzberg historians, Florian M. Beierl, describes exploring the bunker system as a child, and recounts several complicated rumors about additional bunker-level complexes whose existence was never recorded by the Nazis but whose remains are visible today.

Today, one can leave the glories of the mountain air and enter the bunker at two points: through the documentation center and through the Hotel zum Türken. The Türken is very close to the site of the Berghof; during the Nazi era the owners of the Türken, the Schuster family, who were initially Nazi supporters but who complained about the noise and unruliness of Nazi gatherings that took place in their hotel, were forced to flee so that the hotel could become a military barracks; after the war the hotel was returned to the daughter of the prewar owner (and was the only original site returned to a pre–Nazi era owner).5 At the Türken these days, one pays a few euros and goes through a turnstile into the dank, black world of the bunkers. On the walls Nazi sympathizers have drawn Swastikas and others have crossed them out; on the walls, in English, one also finds the kinds of unfortunate commentary pictured in Figure 1.1. It is, therefore, highly problematic that Ingrid Scharfenberg, who ran the Hotel Türken, claimed in 1995 that “there have been no skinheads or their like around here” (qtd. in Weigelt). To the possible objection that the Swastikas I found in the Türken bunker were scribbled after 1995, note that a journalist found “Heil Hitler” and “Tot zu den Juden” (death to Jews) graffitied there in 1984 (see D. Rose). In other words, neo-Nazis, anti-Semites, homophobes, Nazi sympathizers, and others who share their views continue to visit the Obersalzberg as an homage site, and they broadcast their adulatory visits on the Web.

The idyllic image of Hitler feeding deer aboveground on a gorgeous day finds its antithesis here, belowground where the attempted eradication of Germany’s communists, Jews, gypsies, protestors, and queers is celebrated. The juxtaposition of the city belowground and the ultramodern hotel atop the mountain thus functions as an excellent metaphor for the open, airy, happy premodernity of the Nazi image and the dank, dark, hidden technological modernity that strove to achieve Nazi ideals of purity, cleanliness, and harmony with nature. While the modernist aesthetics of the Weimar era were roundly dismissed by the Nazi regime, they were sporadically incorporated into Nazi architecture. Thus, clean divisions between modernist and fascist aesthetics can be hard to maintain. Yet, the Haus Wachenfeld, the simple Alpine house that Hitler bought in 1933 and transformed into the more substantial and impressive Berghof by 1937, adheres to Bavarian country architectural norms far from the modernism expressed in urban Weimar era and even Nazi structures.

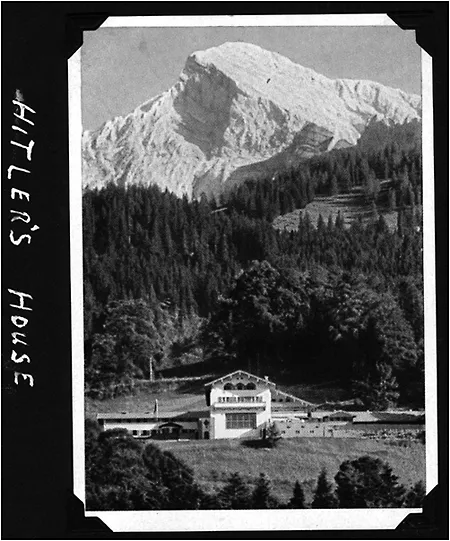

Not only did Hitler construct the elaborate Berghof, but other high-ranking Nazis built or renovated holiday homes nearby, including Architect and Armaments Minister Albert Speer, Reichsmarschall and Luftwaffe head Hermann Göring, and Hitler’s powerful secretary Martin Bormann. No doubt in part because of the beautiful Alpine landscape, Hoffmann took many of his most important propaganda images of the dictator on the Obersalzberg. Some of the most kitschy of them feature Hitler, Swastika clearly visible on his arm, posed against the mountains that, we are no doubt meant to believe, seem to be lending their strength to the dictator (see Hoffmann, Bergen). Others feature Hitler interacting with children, animals, thousands of adoring fans, or other Nazis (see Hoffmann, all). As an indication of how important the Obersalzberg was in Nazi propaganda, consider that one of Hoffmann’s propaganda books, this one for the eyes of occupied France, Un chef et son peuple, opens with a portrait of Hitler quickly followed by an image of the Berghof surrounded by mountains (very similar to Figure 1.2), bearing the following caption: “Au milieu de la grandeur et de la solitude de la nature, c’est ici que s’élaborent les grandes decisions politiques” (“In the midst of the grandeur and the solitude of nature, it is here that he [Hitler] takes his great political decisions”). Strikingly, Hoffmann and the French writer and avid Nazi supporter, Alphonse de Chateaubriant (who wrote the preface to Un chef) chose the photograph

of the Obersalzberg to frame a collection of propaganda images that begin ...