This is a test

- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

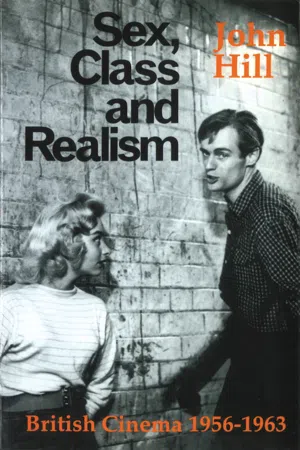

Hugely impressive in its scope, with introductory chapters on social history, the film industry and theories of realism, this indispensable history of these vital years contains unusually fresh discussions of films justly regards as important, alongside those unjustly ignored. The extensive filmography which accompanies Sex, Class and Realism will also prove to be an invaluable reference source in the teaching of British cinema history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sex, Class and Realism by John Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

British Society 1956-63

Almost at once, affluence came hurrying on the heels of penury. Suddenly, the shops were piled high with all sorts of goods. Boom was in the air.1

Ten years ago it was possible, and indeed usual, to look back on the 1950s as an age of prosperity and achievement . . . Today we are more likely to remember the whole period as an age of illusion.2

There can be little doubt that the key to understanding Britain in the 1950s resides in the idea of 'affluence', of a nation moving inexorably forward from post-war austerity and rationing to 'Macmillan's soap-flake Arcadia'3 and purchase on the never-never. It was certainly in this confident, if now rather infamous, spirit that Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was able to proclaim in 1957 that 'most of our people have never had it so good. Go round the country, go to the industrial towns, and you will see a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime - nor indeed ever in the history of this country'.4 To some extent, he was right. As Pinto-Duschinsky has argued, 'From 1951 to 1964 there was uninterrupted full employment, while productivity increased faster than in any other period of comparable length in the twentieth century'.5 During these years, total production (measured at constant prices) increased by 40 per cent, average earnings (allowing for inflation) by 30 per cent, while personal consumption, measured in terms of ownership of cars and televisions, rose from 2\ million to 8 million and 1 million to 13 million respectively.

Conservative pride, in this respect, derived from the fact that they were the government in power throughout this period, winning three elections in a row for the first time in the twentieth century. Having lost office in 1951, Labour had anticipated a retrenchment of traditional Toryism, as the new government reneged on the Attlee administration's commitment to welfare and full employment. In fact, the reverse was true. Following the principles of Rab Butler's Industrial Charter of 1947, the 'New Conservatism' stood by the welfare state and, with the exception of some de-nationalisation, upheld the necessity of state intervention in managing the economy. 'With a few modifications the Conservatives continued Labour's policy,' writes Andrew Gamble. 'So alike did the parties seem, especially in their economic policies, that it appeared indeed as though Mr Butskell had taken over the affairs of the nation.'6

'Butskellism', of course, was the term coined by The Economist to register the similarity in economic policy pursued by the Tory and Labour Chancellors and correctly identified the convergence which was beginning to emerge in the political arena. How this occurred can again be related to the question of affluence. For the Tories, the generals of the 'new affluence', their successful adaptation to and management of a mixed economy seemed to prove, without recourse to traditional moral claims of the superiority of the market and private ownership, their superior fitness to run a welfare capitalist system. Pragmatics supplanted ethics: 'Conservative freedom works'. In the process, it was also believed that the forward march of Labour had been successfully halted:

The fantastic growth of the economy, the spectacular rise in the standard of living, the substantial redistribution of wealth, the generous development of social welfare and the admitted humanisation of private industry, have rendered obsolete the whole intellectual framework within which Socialist discussion used to be conducted.7

Or, as put more succinctly by Macmillan himself, 'the class war is over and we have won'.8 It was a verdict that Labour itself seemed compelled to accept.

Their response, as David Coates suggests, was to move increasingly away from 'class perspectives and socialist rhetoric' towards a revisionism which shared much of the Tory diagnosis.9 The context is clear: Labour were defeated in three successive elections with their share of the vote falling absolutely and proportionately on each occasion. Against this background, it was not surprising that by 1960 Abrams and Rose, in their influential analysis, could ask the question, 'Must Labour Lose?'10 By a process of inversion, the reasons for Tory success became the causes of Labour decline. 'The changing character of labour, full employment, new housing, the new way of life based on the telly, the fridge, the car and the glossy magazines - all have had their effect on our political strength,' observed Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.11 In particular, the successes of Tory rule appeared to have negated the need for Labour's continuing commitment to public ownership of the economy, and it was at the 1959 party conference that Gaitskell led the attack to remove Clause 4 from the party constitution. As Crosland had argued, in his important revisionist work The Future of Socialism, Britain no longer corresponded to a 'classically capitalist society' and Labour's goals of full employment, welfare and abolition of poverty no longer depended on nationalisation but were perfectly compatible with a mixed economy.12

Such economic and social changes were also assumed to be undermining the traditional base of Labour support. 'The revisionists,' writes Coates, 'relied on the studies of voting behaviour to show that the old manual working class was a dwindling section of the labour force, that affluence was in any case mellowing the class dimensions and that the electoral fortunes of the Labour Party turned on its ability to woo the new and rapidly growing white collar, scientific and technical classes who were the key workers in this post-capitalist, scientifically based industrial system.'13 This was a view, once again, shared with the opposition. Thus, the Right Progressives of the Tory Party, gathered round Crossbow, also argued that 'economic growth dissolved the old class structure and created new social groups, in particular affluent workers and the technical intelligentsia, whom a dynamic Toryism could attract'.14 In such a context of political agreement, 'it became plausible to suppose that the consensus between the parties . . . reflected a consensus in the nation. In the spectrum of political opinion from right to left, the majority of the electors had moved towards the middle, the breeding ground of the floaters, leaving only minorities at the extremes . . . Success in the political market now seemed to depend on capturing the centre and winning the support of the floaters'.15 As such, we can see how the 'key terms' of affluence, consensus and 'embourgeoisement' became gathered together 'into an all-embracing myth or explanation of post-war social change'.16 The new post-war mix of Keynes, welfare and capitalism had 'delivered the goods', the prosperity and affluence of the 1950s 'boom period', and in the process secured a 'consensus' amongst political parties on the framework within which governments should now work. At the same time, affluence was dismantling old class barriers, 'embourgeoisifying' the old working class with rises in living standards and an accompanying conversion to 'consensual' middle-class values.17

Barely had the ink dried on such confident prognoses than the reality of Britain's economic difficulties became apparent with the balance of payments crisis in 1961 and subsequent imposition of a pay-pause, credit squeeze and higher taxation by Chancellor Selwyn Lloyd. The roots of this crisis, however, were not local but deep-seated. As Glyn and Sutcliffe put it: 'British capitalism faced increasing competition in world markets: it was continuously losing part of its share of world output and exports. Its level of investment and economic growth was low by international standards. This lack of competitiveness, combined with unwillingness to devalue the exchange rate, led to repeated crises in the balance of payments which were always answered by restrictions on home demand, further checking the rate of growth.'18 Organically related to these problems was the Conservative Party's reluctance to acknowledge its changed role in a world economic and political system characterised by the decline of Empire and increasing American hegemony. Its attempt to maintain sterling as a world currency led to an artificially high exchange rate, inhibiting to domestic growth and vulnerable to runs on the pound, while its commitment to an international political and military role produced an expenditure on defence (7-10 per cent of GNP) higher than nearly any other nation except th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. British Society 1956-63

- 2. The Film Industry: Combine Power and Independent Production

- 3. Narrative and Realism

- 4. The Social Problem Film I

- 5. The Social Problem Film II

- 6. Working-Class Realism I

- 7. Working-Class Realism II

- Conclusion

- Select Filmography

- Index

- eCopyright