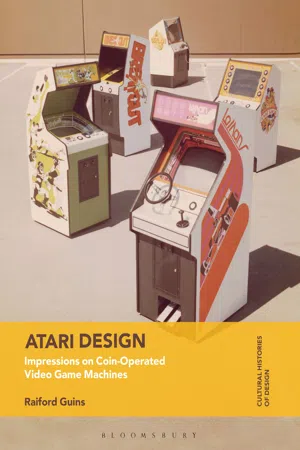

![]()

1

START WITH A CLEAN PIECE OF PAPER

A good job of body styling should come across like a good musical—no fussing after big, timeless abstract virtues, but maximum glitter and maximum impact.

Reyner Banham, “Vehicles of Desire,” 1955

Man, That Thing Needs Some Help

Years after graduating from San Jose State University’s program in Industrial Design, Peter Takaichi and Regan Cheng would, occasionally, revisit their alma mater to attend senior-year presentations. End-of-year shows typically showcased student work to fellow classmates, family, faculty, and members of industry scouting soon-to-be-minted young talent. To the bemusement of the pair, the senior project assignment one year was to design a coin-operated video game cabinet. In 1981 SJSU’s The Spartan newspaper reported on the university’s Industrial Design program and featured Takaichi, by then manager of Atari’s Industrial Design division to demonstrate the “ways industrial design impacts on human life” in the spheres of amusement, leisure, and social experience.1 Coin-op video game machines had come of age in industrial design, at least on the campus of SJSU.

1973 was different. In need of design interns, architect turned Atari manager of Industrial Design George Faraco visited SJSU to pitch a newly formed coin-op amusement company with a single product, Pong.2 Interested in the prospect of an internship in industrial design during his junior year, Takaichi landed the job. This paid internship required around thirty hours a week on top of his full course load at SJSU starting in June 1973. A few days later Cheng, eager to join his roommate, also interviewed. They both worked through their senior year to eventually become full-time employees as associate industrial designers upon graduation, not a small feat considering that many recent graduates found it challenging to secure full-time positions during the 1973–5 period of US economic stagflation when the command to “economize”—reduce manufacturing and distribution costs—coursed through industry in the form of layoffs and hiring freezes.

Cheng lends insight into Faraco’s reason for visiting the campus: “Man, that thing needs some help,” is how he recalls Faraco’s discerning view on Pong’s cabinet.3 [Plate 1.1] Recruiting industrial design interns at Atari was Faraco’s strategy to improve cabinet design, to have the budding company’s coin-op products designed by professionals. Less than a year after Atari’s launch, it had already invested wisely in industrial design with the hiring of Takaichi and Cheng. Industrial design was a supporting pillar of Atari’s game development structure right alongside electrical engineering. Fun, competitive, challenging game play was not enough. The game’s cabinet had to convince distributors and operators—the consumers of coin-op products—that it would attract users across diverse locations ranging from game rooms and arcades to cocktail lounges and bars by adding to rather than detracting from interior functionality and ambiance.

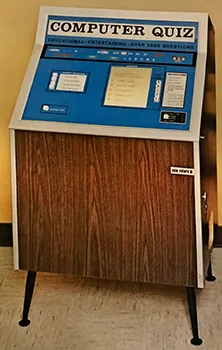

This absence of industrial designers during the development of the Pong cabinet begs the question: how was it designed? According to Al Alcorn the form, shape, and style of the Pong cabinet reflected a co-design process between Bushnell, Ted Dabney (who provided the drawing for their pre-production cabinets4), and P.S. Hurlbut Woodworking Inc. Dabney, responsible for building and decorating the Pong prototype, applied a similar cabinet style to Atari’s Pong pre-production test units: wood veneer laminate encasing a single hue outer bezel fronting an internal black bezel outlining the television set. Dabney points to Nutting Associate’s Computer Quiz (1967), an electronic coin-op machine he encountered while working with the company on Computer Space (1971), as the “guide” for the prototype cabinet.5 [Figure 1.1] “Industrial design” as a professional practice and process at Atari was an amateur undertaking in 1972 and early 1973. “Basically we said we need a panel for the knobs,” Bushnell rejoins, “and we got to mount the monitor here.”6 Alcorn acquiesces on the co-design process: many of the cabinet components were “pre-bought” like limonite, particle board with laminate already applied, and the plastic T-Molding. “They did all of that,” Alcorn confirms in regards to Hurlbut’s role, on account of the three-men operation responsible for developing Pong “not having any money.”7

Figure 1.1 Promotional photograph for Nutting Associates’ Computer Quiz, 1967. Reproduced with permission from The Strong, Rochester, NY.

Hurlbut received 4×6ft and 4×8ft vinyl laminate particle board panels from Roseburg Lumber Co of Oregon. Roseburg’s newsletter, Roseburg Woodsman, ran a feature story on Atari that details the process that its product would go through at Hurlbut: panels were run “through routers or table saws, where they were shaped, drilled, and rabbeted, and cut to the exact specification for each game cabinet. After decorative T-moldings are added, the panels are trucked down to Atari.”8 Atari could not afford to hire designers at this point in the company’s history. The exact number of upright Pong units sold remains unspecified in accessible surviving documentation; even verbal accounts vary on the exact figure.9 In Atari’s first fiscal year (June 1972 to May 1973) net sales were recorded at $3.2 million.10 Predictions for the second and third fiscal years estimated profits between $10 and $12 million based upon the release of new product, prompting the need for professionally trained industrial designers, hence Faraco’s venture to SJSU.

How did the profession of industrial design respond to Dabney and Bushnell’s Computer Space, the first mass produced coin-op video game, as well as to the success of Pong and the introduction of industrial designers like Takaichi and Cheng? Scrutinizing the aged pages of trade publication magazine, Industrial Design, in years corresponding to each machine’s launch, one is hard pressed to find any evidence of their existence as industrial designed products. Industrial Design’s “19th Annual Design Review” for 1972 celebrates improvements in equipment and instrumentation design, emphasizing simplification in both form and practice via the likes of Hewlett-Packard’s Model 35 pocket calculator and a John Deer Model 4430 Row Crop Tractor, designed by Henry Dreyfuss Associates. Contract and residential design showcases a number of impressive office chairs, a spun metal coffee table, and the American Standard’s Posturemold toilet seat ergonomically designed to provide “the most suitable body posture during elimination.”11 Consumer product entries included an injection molded backpack, a lightweight sailboat, the Pocket Instamatic camera, Lunar I black and white TV, AM/FM radio with digital clock, and Mymate interlocking building sets for children.

Industrial Design’s “20th Annual Design Review,” published December 1973, a full year after Pong’s release, includes “93 products and projects,” all of which “meet standards of aesthetics and ergonomics,” above and beyond the 545 entries nominated.12 Categories for consideration were “equipment and instrumentation,” “contract and residential,” with office furniture and work spaces coexisting alongside outdoor leisure furniture like the Samsonite 5400 Body Glove chaise lounge, “consumer products,” and additional categories such as “visual communication,” covering packaging, promotional materials, brochures, posters, and catalogs, and, finally, “environments,” like lobbies, galleries, parks, hospitals, and retail. Where exactly would a coin-op amusement machine fit within these categories? The publicness and social component of competitive play of both Computer Space and Pong defies the category of “contract and residential.” “Consumer Products” would be the most fitting space where these machines could share pages with tennis rackets, ski googles, another sailboat, portable movie cameras, projection television, and wooden children’s toys. Bear in mind though that a coin-op video game machine is a product for distributors and operators but more of a service (provider of a game) or experience for its users: that quarter inserted rents space and time at a control panel, user skill aided by “extra lives” extends the duration of play. Perhaps then the category of “environmental” is most applicable considering the assortment of public spaces that these machines would occupy throughout the 1970s.

Ensuing annual reviews do not include Atari coin-op machines. The answer to my question becomes rather obvious. At least, this is the impression one infers when perusing Industrial Design, the major trade magazine of the industry in the US. Products designed for amusement—games in particular—receive scant attention within the publication unless one feels that recreation vehicles like sailboats fulfill this niche. The absence is less a matter of a new allusive product type, one fitting awkwardly within the magazine’s existing categories for design review, than Computer Space and Pong not being products of professional industrial design. As we have seen above, the Pong cabinet was coordinated across a woodworking manufacturer and former Ampex engineers while Computer Space, as we will observe below, gained its lauded “futuristic” sculpted form by way of Bushnell experimenting in cabinet design one evening, an autodidactic achievement realized through plasticine modeling clay. [Plate 1.2] While words like “shape,” “form,” and even “design” can, and ought to, be applied to these products, they nevertheless were not products of professional industrial design. They were not given form by those trained in the field. Drawings, renderings, materials studies, human factor tests, measurements, mock-ups, models (other than the one), meetings with clients were not, according to documentation and the source behind the hands molding the form for Computer Space, observed to any degree of industrial design orthodoxy.

In no way does my asseveration dismiss the resultant cabinet designs for either Computer Space or Pong. Quite the opposite. When Bushnell conceptualized the cabinet for Computer Space, a distinct fiberglass container to package and physically support a commercial iteration of the minicomputer hack/demo, Spacewar! (1962), he professed two interrelated design goals: construct a cabinet that is “kind of spacy” and make it “look cool.”13 Computer Space’s significance for the history of games is long touted, ostensibly an origin story of an industry and technological “first” met with “failure” in sales, large-scale cultural adoption, and general impact on the industry.14 My intention here is not to trample too far down that well-worn path but to steer clear of the habitual game-centric history in order to interpose Computer Space’s cabinet into the history of design. Consensus voiced on Computer Space’s cabinet is that its design looked “strange” or “futuristic” in contrast to the reigning styles of coin-op products. If so, the question for me then is what did these descriptors, or Bushnell’s own “spacy,” mean in 1971, a few years after the Apollo 11 mission landed on Earth’s Moon, but seemingly light years away from the so-called “space-age” popular design manifest in the Populuxe, Googie style, and “Boomerang modernism” of the 1950s and 1960s? Comparing Computer Space to other coin-op machines at taverns, game rooms, or amusement arcades obscures a pronounced aesthetic connection to other Cold War-era products expressive of playful forms and optimistic futures cum late pop style applied in the vibrant plastics of, say, Eero Aarnio’s Pastil Chair or Panasonic’s Toot-A-Loop Transistor Radios. Situating Computer Space’s cabinet within this ethos in the history of design places Bushnell’s cabinet concept outside of the narrow straits of game history and within a much broader history of product design.

If Computer Space is revered for its “BEAUTIFUL SPACE-AGE CABINET,” to quote Nutting Associate’s sell-sheet,15 such exaltation is rarely directed at Pong; a short-stature, woodgrain veneer-sided, minimal cabinet lacking the arresting stylized qualities of its predecessor. Pong was more conventional than Computer Space—at its most reductive, a 13-inch black and white off-the-shelf TV placed on another shelf within a no-nonsense, functional cabinet—nevertheless it still demonstrated a design sensibility that distinguished it from other machines on the market: modest, understated, as compared to the loud and flashy cabinet designs of EM and pinball machines. Pong’s cabinet design, like that of Computer Space, was intentional: its form, declared by Bushnell on Atari’s sell-sheet as “Low Key Cabinet, Suitable for Sophisticated Locations,” expanded the social and commercial spaces open to coin-op amusements. Cabinet design proved decisive in delivering a fun, competitive two-player video game to users across varied locations. Although the Pong ca...