This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Problems of Economic Policy (Routledge Revivals)

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1977, this is an applied economics text, in which the basic theory of any introductory economics couurse is applied to a whole range of UK macro- and micro-economic policy issues. The book is designed specifically for first and second year university students, with the aim of demonstrating the relevance of theory to policy, how theory can be applied to policy problems and, in the process, to improve their understanding of the theory itself.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Problems of Economic Policy (Routledge Revivals) by Keith Hartley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

Methodology

Chapter 1

The Economists’ Approach to Policy Problems

INTRODUCTION

Economic policy leads to a great deal of controversy between economists. Disagreements arise about the aims of public policy, the importance or ‘weights’ to be attached to various aims, the relevance of alternative theories in explaining the causes of policy problems and the appropriateness and desirability of particular policy solutions.1 The problems which confronted the British economy in the 1970s illustrate some of these controversies. In this period, unemployment and inflation were major issues but politicians and others differed in the emphasis which they were willing to place on each of these. Some emphasised, or valued highly, the maintenance of full employment whilst others preferred more price stability. Disputes also arose over the precise causes of the inflation and the nature of unemployment in this period: an area where economic theory and the evidence on the predictive accuracy of alternative theories is relevant. For example, is inflation always a monetary phenomenon or do trade unions matter? Disagreements appeared over the choice of policy solutions, especially the appropriateness and desirability of deflation and incomes policies. Worries were expressed about conflicts in policy objectives such as the likely effects on inflation and the balance of payments of policies aimed at maintaining full employment. But policy debates were not confined to macro-economics. Micro-economic policy, embracing product and factor markets, was also controversial.

In the 1970s, there were disagreements about Britain’s membership of the European Economic Community, subsidies to lame ducks, trade unions, the housing market and rent control, merger policy, the nationalised industries, worker’s co-operatives and the extent of state ownership, to name but a few. Criticism surrounded such policy instruments as the Selective Employment Tax, the Regional Employment Premium, the National Board for Prices and Incomes, the Industrial Relations Act, 1971–4, and the National Enterprise Board. The list is illustrative rather than comprehensive. Debate has also intensified over the distribution of income and wealth in the UK. The distributional implications of such alternative policies as deflation, incomes policy, lame ducks, rent control, agricultural support policy and wealth taxes are consciously assessed and compared with some criteria relating to an ‘ideal’ distribution. Inevitably, disagreements arise since on each policy issue everyone has an opinion and these differ. This book aims to identify the general contribution of economic theory to current debates about British economic policy.

METHODOLOGY: HOW DO ECONOMISTS APPROACH POLICY PROBLEMS?

In approaching policy problems, economists seek answers to three questions:

(1) What is the problem? For example, in the 1970s, successive British governments were concerned with inflation and unemployment: hence price stability and full employment were two policy targets.

(2) What are the causes of the problem? Economists use economic theory to explain the causes of events which are of concern to policy-makers. For example, inflation might be explained by demand-pull and/or cost-push theories. The acceptability of a particular theory of inflation will depend on whether it fits the facts.

(3) What can we do about the problem? Frequently, theory suggests alternative policy solutions or instruments. Once again, inflation provides examples with the debate between such alternatives as monetary, fiscal and pay policies. In this situation, theory can be used to predict the likely effects of alternatives and the results presented to the policy-makers. The politician is then faced with a classic problem of choice between alternatives: the situation is similar to that confronting utility-maximising consumers and other economic agents. Standard utility-maximising behaviour requires the policy-maker to choose the least-cost method of achieving the aims of policy (see Chapter 4). Least-cost is thus related to the decision-maker’s preference function. It means that costs are subjective in that the policy-maker will attempt to minimise the sacrifices, including the sacrifice of other policy aims, involved in pursuing a particular course of action. For example, in choosing between alternative policies to control inflation, he will act according to his preferences and select the policy which he believes will have the minimum of adverse effects on the other policy targets such as employment, growth and income distribution.

Each of these three general questions will be expanded in the remainder of this chapter. Consideration will be given to the policy objectives of governments, the relevance of economic theory to policy, and the relationship between policy objectives and instruments. The technical equipment used consists of production possibility boundaries and some general principles of economic methodology.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM? THE OBJECTIVES OF ECONOMIC POLICY

Any logical assessment of economic policy in the UK must start with the basic question of the Government’s policy objectives: What is the Government trying to achieve? What is its objective function? What is it trying to maximise?

In the post-war period, the various British governments have been concerned with six objectives relating to:

(1) Employment.

(2) Price stability.

(3) The balance of payments.

(4) Economic growth.

(5) The distribution of income and wealth.

(6) Efficiency in the use of resources.

Whilst various British governments have accepted these broad objectives, they have differed in the importance or the ‘weights’ which they have placed on each aim. Labour governments have traditionally emphasised employment, growth and distributional objectives whilst Conservative administrations appear to have attached greater importance to price stability and balance of payments objectives. Similarly, the two political parties have differed in their approaches to efficiency in resource-use, one emphasising state intervention to replace or limit the operation of private markets, the other believing more in the virtues of private enterprise, competition and individual consumer choice.

Most of the above objectives are widely known, although a concern with efficiency probably requires some explanation. A requirement for economic efficiency is that it must be impossible to raise the output of one good without producing less of another. On this basis, inefficiency in production exists if, for example, a re-allocation of labour or capital will increase total output. The inclusion of the efficiency objective arises from the observation that various British governments have attempted to raise output through improving the efficiency with which resources are used in the economy. For example, governments have been concerned with the allocation of resources, especially labour, between regions and industries and with promoting a re-allocation of labour from the declining to the expanding sectors of the economy. The coal industry is a classic example, where there has been a long-run decline in employment and a re-allocation of labour both within the coal industry and to other industries. Governments have also been interested in the structure of industries and the organisation of markets. For example, the Labour Government’s Industrial Reorganisation Corporation supported mergers to encourage the formation of larger firms capable of obtaining economies of scale and so reducing unit costs (see Chapters 9 and 10). Competition policy also exists to regulate any mis-allocation of resources due to monopoly. Finally, government support for productivity bargaining, as occurred in the 1960s, is a further example of the general concern with efficiency in resource-use. In these ways, governments have attempted to reach the economy’s production possibility boundary.

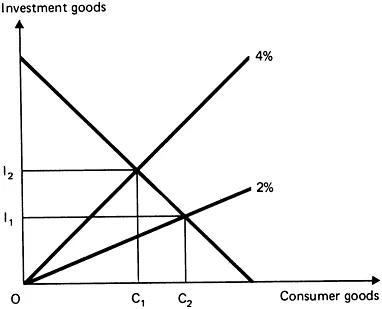

Once an economy’s resources are fully and efficiently employed, it will be operating on its production possibility boundary. A simple example, assuming constant returns to scale, is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

The production possibility frontier in Figure 1.1 shows the various combinations of consumer and investment goods2 which can be produced when an economy’s resources are fully and efficiently employed. With the unemployment which existed in the mid-1970s, the UK was clearly operating at a point within its production possibility boundary. Even at full employment, it is likely that some inefficiency exists in all economies. Information might be inadequate and firms might not be profit-maximisers, so that markets might ‘fail’ to work properly. Questions then arise about the additional costs of reducing inefficiency in relation to the expected benefits. In a world of scarcity, where public policies are not costless, it will probably be too costly to completely eliminate all inefficiencies: there will remain an ‘optimal’ (positive) amount of inefficiency.

Once the boundary is reached or approximated, resources become scarce and have alternative uses. Consider the case of economic growth, which can be represented by an outward shift in the production possibility boundary. If the Government’s preference function is such that it prefers to raise the growth rate from, say, 2 per cent to 4 per cent, more investment will be required. As Figure 1.1 shows, present consumption of C2C1 is sacrificed for the extra investment required to raise the growth rate. In other words, where resources are scarce, governments have to choose between alternatives. They have to choose between, say, more or less growth with the implications for consumption levels amongst present and future generations. Such a choice involves a distributional judgement. Policy-makers cannot avoid choices. Defence or schools, Concordes or hospitals, and space programmes or houses? In each case, choices are required and the ultimate decision will be based on what a government is trying to achieve. For example, decisions might reflect a government’s beliefs about the likely results of its policies in making people ‘better or worse off’. This explanation of government behaviour will be critically assessed in Chapter 2.

So far, we have identified the broad objectives of UK economic policy. But, before the economist can proceed to analyse policy issues, he requires a much clearer specification of the objectives. Answers will be required to questions about the objectives:3

(1) What is meant by a government’s commitment to maintaining a ‘high and stable level of employment’? Is an unemployment rate of, say, 2 per cent to 3 per cent consistent with a ‘high’ level of employment? Does ‘stability’ require unemployment rates to fluctuate within some relatively narrow range, say, 1·5 per cent to 3·5 per cent and how tolerable are departures from these targets?

(2) What is meant by the frequently claimed objective of maintaining price stability? Does it mean no increase in domestic prices? Or is an increase in prices of, say, 5 per cent per year consistent with stability? Alternatively, are governments concerned with relative price stability, namely, domestic price movements in relation to price changes amongst the UK’s major foreign competitors?

(3) What is the meaning of a ‘strong’ balance of payments? For example, in the mid-1950s the aim of policy-makers was to achieve a current account surplus of between £300m. and £350m. per year, whilst in the early 1960s the target was raised to about £450m. per year.4 In addition, until the early 1970s, the balance of payments targets of successive governments was associated with a desire to maintain the exchange rate for sterling.

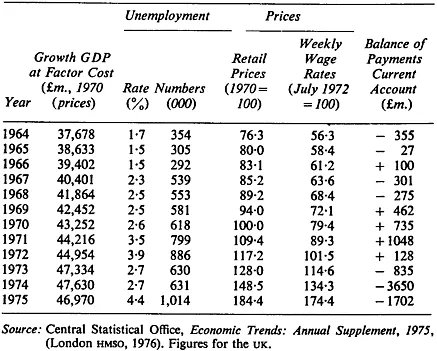

These are the type of questions which economists have to ask about policy objectives. The answers enable the economist to identify the problems which concern policy-makers and also to assess whether a government has actually achieved its declared objectives. Governments are understandably vague and reluctant to quantify both their aims and the importance they attach to each one. Policy objectives are frequently expressed in terms which bear a marked resemblance to the health of some ideal individual (‘strong’, ‘healthy’, ‘vigorous’). In the circumstances, a start can be made in assessing government performance by considering the evidence on unemployment, prices, the balance of payments and growth for the UK, as shown in Table 1.1.5

For 1964–75, unemployment fluctuated between 1·5 per cent and 4·4 per cent. After 1945, unemployment of 3 per cent was accepted as consistent with full employment, although the target was later reduced below 2·5 per cent. On this basis, the employment record in the 1970s was below target. It is, however, possible that the nature of unemployment has changed compared with the 1960s, requiring a revision in the full employment target. Alternatively, the employment target might have been sacrificed for other policy ends. As for prices, at no point in the period has there been price stability in the sense of no change in the retail price index. Both prices and wages have risen continuously, with the annual increases being at a minimum in 1966–7, and an unprecedented maximum in 1974–5—each being periods of rising unemployment! The balance of payments has also fluctuated widely. It varied between a surplus of over £1,000m. in 1971 and a deficit of £3,650m. in 1974, much of which was due to the rise in the prices of oil and raw materials. Only between 1969 and 1971 did the UK achieve the target of a current account surplus of over £300m. per year and this period followed the devaluation of 1967 and was characterised by unemployment rates of 2.5 per cent and over.

Table 1.1

Growth, as measured by real GDP, generally showed an upward trend, with a large increase in 1972–3: this increase was associated with substantial reductions in the unemployment rate and a deterioration in the balance of payments. In fact, a distinction has to be made between variations in resource-use and changes in long-run productive potential. The latter is a more accurate indicator of the economy’s growth performance and might be approximated by comparing periods of similar unemployment rates. If the National Plan’s target growth rate had been achieved, GDP in 1970 would have been some £47,000m., a figure which was not reached until 1973. Table 1.1 also shows the changing magnitude of the problems confronting British governments in the 1970s. Compared with the 1960s, the scale of the unemployment, inflation and the balance of payments problems was unprecedented.

ECONOMIC THEORY AND PUBLIC POLICY: WHAT ARE THE CAUSES OF THE PROBLEM?

The emphasis so far has been on identif...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Contents

- Part I Methodology

- Part II Macro-Economic Policy

- Part III Micro-Economic Policy

- Notes

- Further Reading and Questions

- Index