1

Framing place and process

The stars of the catwalk have just returned from the pilgrimage to Mecca. Clear symbols of their newly acquired haji status are visible in the form of various head coverings. As with their outfits, the head coverings come in many styles, colours, and fabrics. It is a little after seven in the Indonesian town of Sengkang when the MC calls out the name of the first participant in the evening’s main event, a Muslim fashion parade. The first contestant saunters onto the stage, slowly and demurely doing one turn and then another. Twenty people are vying to be crowned the winner of this event and thus be publicly recognized as the most elegant embodiment of Muslim femininity in Sengkang. The audience is jammed tight in the ground floor venue, leaving little room for the three judges. The judges have, by necessity, all been on the hajj and are former winners of this competition.

When all the contestants have had their turn on the catwalk, the head judge takes the microphone from the MC and tells the audience that the quality of the contestants was quite high. The judge notes, however, that some of the contestants did not exhibit the qualities required in respect to proper Muslim femininity. What is needed, the judge reveals, is an ability to walk with composure, to walk softly and slowly, taking small, delicate steps. Turning should be controlled, balanced, and seamless. Poses should be refined, elegant, supple, and poised. Unfortunately some contestants, the judge announces, were too quick in their steps, too unbalanced in their turns, and too stiff in their poses. The judge also vocally assesses attire, reminding everyone that the body should be covered yet the feminine form should still be visible. The selection of colours, styles, and materials is critiqued and deemed to be of a generally acceptable standard. Accessories are an important part of the presentation, the judge states. As such, appropriate handbags, shoes, ear-rings, necklaces, hairstyles and cosmetics are all essential. However, not all of the contestants’ accessories conformed to the particular image of Muslim femininity that the judges value. The head judge then announces the decision as to which contestant best exemplifies the image of Muslim femininity. The winner and runner-up are presented with trophies and the audience claps enthusiastically in recognition of their achievements.

The event proceeds in a manner that conforms to beauty pageant norms found around Indonesia and elsewhere. A rigid model of femininity is presented and contestants strive to emulate this model as precisely as possible. Contestants are ranked against each other, clearly marking which contestant epitomizes the desired model and which falls short. Such events not only mirror a more general obsession with beauty and appearance in Indonesia, but also highlight the popularity of a particular contemporary Islamic aesthetic. However, there is one aspect of this competition that departs from other similar events; the participants in this fashion parade are not women, but transgender males.

The vignette above introduces well the complexities of gender in Indonesia. On the one hand there is a seemingly specific gendered model of modest, pious subjecthood, represented most compellingly for many in the Islamic feminine ideal outlined in part by the head judge. Yet, on the other hand, there is a playfulness attached to gendered subjectivities that allows, for instance, males to emulate femininity publicly and be rewarded for doing so. In drawing out the issues that events such as this beauty pageant raise, this book informs contemporary debates concerning gender, sex, and sexuality. It addresses critical aspects of the construction of gendered selves such as embodiment, desire, performativity. The text also explores the interplay between religion, the local, the nation, and the global, in both contemporary and historical contexts, to show how discursive structures shape gendered positions. Furthermore, gender ideals are interrogated while concomitantly exploring ways in which queer subjects interrelate with normative gender models. In highlighting these issues the ethnographic approach used here enables focus to remain on the particularities of gendered subject positions while drawing on a range of theories to elucidate the analysis.

The book’s chapters progressively build a picture of gender in Indonesia. By journeying through various discourses, it weaves together theoretical understandings of gender with gender processes and practices. Initially, the text provides a chronology of understandings of gender, indexing moves in dominant theories from Mead to Butler and beyond. Ideas of the body are then drawn on, analysing how both theorists and individuals account for the body in respect to gender. In so doing, sexuality, performance, and spirituality are explored within the context of recent developments in transgender theory.

To ensure cross-cultural studies of gender do not essentialize a timeless subject, Johnson (1997) stresses the need to look at shifting historical contexts and spatial fields in which identities and practices have developed as products of political and cultural engagements. This book thus investigates the real and imagined past of Bugis South Sulawesi, exploring ways in which the past is evoked in contemporary society. I analyze sources of information available on the past before moving to explore roles variously gendered beings are commonly considered to have assumed.

A substantial part of the volume concentrates on ways in which individuals become properly gendered members of society. In addition to showing the centrality of gender in the archipelago, the book outlines Indonesian and Bugis gender ideals of masculinity and femininity as disseminated through government ideology, promoted through familial values, supported through discourses of courtship and marriage, and spread through the mass media. Recognizing the importance of discussing Islam, I draw specific links between Islam in Indonesia and that nation’s complex norms of gender and sexuality.

While the aim of the work is to show how people engage with gender, the book’s specific focus is on non-normative genders. As such, chapters are dedicated to the subject positions of calalai (transgender females), calabai (transgender males), and androgynous bissu shamans. Within these respective chapters, I examine presentations of self and recraftings of masculinity and femininity and interrogate issues of embodiment, sexuality, and individual relationships with Islam and general society. As with the text as a whole, the theoretical analysis inherent in these chapters is fleshed out with rich ethnographic data.

The setting for this exploration is the nation-state of Indonesia (Figure 1.1). While the Indonesian government is overtly heteronormative, the state has maintained a relatively neutral legal stance toward transgenderism and homosexuality. There are no laws against transgender behaviour or same-sex acts between consenting adults. Even proposed revisions to the Penal Code do not seek to outlaw consenting adult homosexuality (Oetomo, 2006). For instance, the proposed revised Article 493 reads ‘A person who engages in indecent acts (perbuatan cabul) with another person of the same sex (sama jenis kelaminnya) under 18 years of age will receive a sentence of from one to seven years’ (cited in Blackwood, 2007: 301). This revision changes the current law only to specify a minimum age limit and increase the maximum sentence by two years. What has long been penalized, though, and is reaffirmed in the proposed revisions, is any sexual relations between a man and woman outside marriage (zina), and any sexual relations within

marriage other than heterosexual penile-vaginal sex (Blackwood, 2007: 301). Blackwood (2007: 302) argues that surrounding debates over these proposals have moved the ‘discursive terrain away from the definition of properly gendered citizens to questions concerning the liberal notion of human rights (of privacy, of freedom of expression and association) versus the moral sensibilities of the people.’ Prior to the 1990s the deployment of gender was enough to produce heteronormative reproductive citizens. However, the proposed revisions to the Penal Code more closely link proper citizenship to definitions of sexual acts (Blackwood, 2007: 304). Yet while this shift in focus further codifies heterosexual relations, same-sex relations continue to be secondary considerations.

While Indonesia is home to more Muslims than any other country, it is a pluralist nation with around 20 million Protestants and Catholics, 5 million Hindus and 2.5 million Buddhists, out of a total population of almost 235 million people. Most Muslims are Sunni, but there is a wide range of variations, including a growing number of Sufi adherents (Howell, 2001, 2005). Although Indonesia allows religious choice, Howell (2005) notes that the nation follows a policy of delimited religious pluralism – meaning people are technically free to follow their own religion as long as it is one of six world religions recognized by Indonesia – those mentioned above with the recent addition of Confucianism.

Geographically, the archipelago of Indonesia encases some 6000 inhabited islands, with sovereignty over another 11,000. There are around 500 ethnic groups, and over 737 living languages, with 269 of them spoken in the disputed province of Papua alone (Gordon, 2005). The geographic terrain and diversity of language caused logistical problems for both colonialism and the subsequent independence movement. Moves were thus made to unify Indonesia under the Malay language and conceptualize it as an archipelagic nation.

Since independence from Dutch and Japanese occupation in 1945, and up until 1998, Indonesia had only two presidents: Sukarno followed by Suharto. In the decade since Suharto’s forced resignation there have been four presidents: B. J. Habibie, Abdurachman Wahid, Megawati Sukarnoputri and current president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. There have also been continuing separatist movements in Aceh and Papua, with East Timor finally gaining independence in 2002. In addition, regions such as South Sulawesi are requesting more autonomy and there are increasing calls to decentralize power. The impact of such moves on marginal communities is a current topic of debate (Aragon, 2007; Buehler, 2007; Buehler and Tan, 2007; Duncan, 2007).

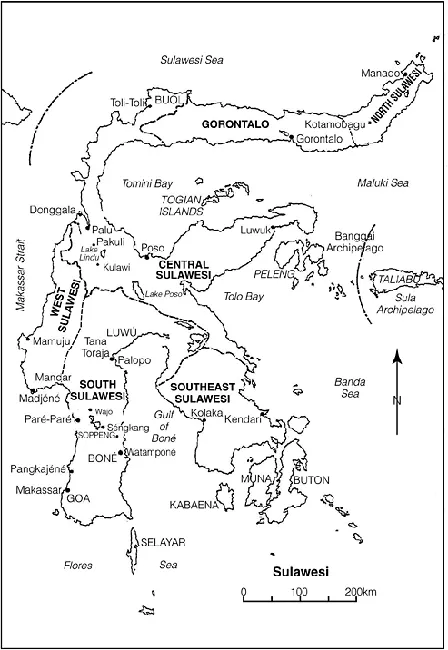

While focusing on Indonesia, most of the ethnographic material contained in this book is drawn from Sulawesi (Figure 1.2). Likened by some in shape to a Freudian doodle, the island of Sulawesi spreads its tentacles between Borneo to the West, Maluku to the east, the Philippines to the north and Flores to the south. The island is the eleventh largest in the world and it is home to around fifteen million people speaking over fifty different languages. The largest ethnic group, Bugis, number almost five and a half million people, most of who live in the province of South Sulawesi – elsewhere Idrus (2003) provides further statistical information on the region. Bugis continue to have influence outside South Sulawesi, though. In the

realm of politics, for example, a number of Bugis, including Sulawesi-born former President B. J. Habibie, the long-serving Mayor of East Jakarta, Andi Mappaganti, and the current spokesperson for President Yudhoyono, Andi Mallarangeng, have disrupted Javanese political domination.

The capital city of South Sulawesi, Makassar (once known as Ujung Pandang) became a dominant trading centre of eastern Indonesia as early as the sixteenth century and it went on to become one of the sixth largest cities in Southeast Asia, indeed it was comparable in size to many European capitals (Reid, 2000: 58). In 1605, the ruler of the state of Goa in southern Sulawesi converted to Islam and subsequently sought to impose Islam on neighbouring rulers (Ricklefs, 1993: 48). While today over 90 per cent of Bugis adhere to Islam, the region’s relatively tolerant nature has meant other religions and belief systems continue to be expressed, if at times covertly. In other Sulawesi areas, though, religious rivalries have played out with devastating effects, such as in neighbouring Poso where there have been recent violent clashes between Christians and Muslims (Aragon, 2001, 2005).

Driving north from Makassar a detour into the centre of the peninsula takes travellers to the bustling lake-side town of Sengkang. While located less than two hundred kilometres from the capital, the mountainous jungle terrain means the journey rarely takes less than five hours by car. Danau Tempe is a shallow lake fringed by beautiful wetlands that provide sanctuary for many types of birdlife. Fisherfolk live on the lake for part or all of the year in floating homes (bola monang, B) tethered by a bamboo pole. Living on the lake facilitates catching and drying fish that are then taken to market on motorized canoes. However, with consistent reports that the lake is drying up, people are increasingly talking about the difficulties of sustaining such a livelihood. Sengkang is also a key centre of silk production and it is not uncommon when walking around the villages surrounding the town to hear the click-clack of hand-looms weaving silk sarong. Unlike their northern Toraja neighbours, whose funeral ceremonies are one of the most famous attractions in Sulawesi (Bigalke, 2005; Volkman, 1985), the most celebrated life-cycle ritual for Bugis are highly elaborate and lengthy weddings (Davies, 2007a; Idrus, 2003, 2004; Millar, 1989).1

The ethnographic material presented in this book has been collected over a period of more than two years spent in Indonesia, primarily in South Sulawesi, spread between 1998 and 2008, with the most sustained period of field work being twelve months between 1999 and 2000. The book provides readers with rich ethnographic material that is used to draw out particular theoretical propositions. Following Geertz (1973b), I acknowledge that thick description can serve as a robust source of information. Valocchi (2005: 751) further notes that, ‘ethnography is especially well suited to handle the methodological challenges associated with distinguishing practices, identities, and hegemonic structures of gender and sexuality, an important component of a queer perspective.’ Boellstorff (2006c) also affirms the strengths of anthropological ethnography in fleshing out queer studies as this approach involves a mutually constitutive triad of method, data, and theory. Additionally, Stryker (2004: 214) comments that with solid ethnographic grounding, accounts are less likely to reproduce ‘the power structures of colonialism by subsuming non-Western configurations of personhood into Western constructs of sexuality and gender.’ Ethnographic material is certainly not without fault, though, and the data needs rigorous reflection and examination, which this volume undertakes.

The book’s ethnographic analysis is grounded in my interpretation of what some people told me about gender and what I have observed. I have discussed my work and findings at length with Bugis friends and colleagues, as well as with scholars of Indonesia and gender. My analytical approach is further informed by a number of general fields of study, such as ethnographic work on gender and sexuality, writings by and about transgender individuals and issues, works of gender, sexuality and queer theory, and material on Indonesia and Southeast Asia. While my analyses have been generally affirmed, I certainly cannot claim to speak for a majority of Bugis. Yet Chodorow (1995: 522) notes that we can generalize usefully about gender within particular cultural groups, although ‘we need to be careful that our claims do not go beyond our data base, or that we specify the basis of our speculations ...