Chapter One

Didactic Translation: Religious Texts, Courtesy Books, Schoolbooks, and Political Persuasion

The earliest history of children’s literature in English is dominated by translations. Versions of the Christian scriptures and the Bible in Old and Middle English were for centuries the translated texts children encountered most frequently, especially after the publication of John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible from Latin in the fourteenth century, William Tyndale’s from Greek and Hebrew (1524 onwards), and the enduring King James version of 1611. Once the band of forty-seven translators appointed by James I had reworked existing versions with reference to Hebrew, Greek, and Latin sources to create a poetic text, its sonorous cadences became familiar to children in church, school, and home. Moreover, children’s earliest reading primers, alphabets covered with thin layers of sheep’s horn and tacked to paddles in so-called ‘horn books’, included a translation of the Lord’s prayer.

Possibly the earliest record of a translator’s intention to write specifically for a child audience, however, is a comment by the dying English monk Bede (c.673–755), who explained his desire to render into the English vernacular the Latin of Isidore and St John as follows: ‘I cannot have my children learning what is not true’ (Bede, 1969: 583, cited in Burrow, 2008). Just over a century later, King Alfred (849–899) initiated a policy of translation from Latin with the express purpose, as stated in the preface to his own version of Gregory’s Pastoral Care, of encouraging that ‘the youth of free men who are now in England … be set to learning … until the time when they can well read English writings’ (Wilcox, 2006: 35)1. Alfred’s determination that his young subjects should learn to read English was reiterated by the Benedictine monk AElfric of Eynsham (c.955–1010), a translator of parts of the Old Testament from Latin, in his translation into English of the standard Latin grammar of Priscian. AElfric claims that he has applied himself to translating:

These early attempts by Bede, Alfred, and AElfric to introduce the English language into educational texts make it clear that the role of translation in medieval texts for children can only be fully understood by taking into account the linguistic history of the British Isles, as well as the distinction between the spoken English vernacular and Latin. That history was further complicated after the invasion and conquest of Britain by the Norman French in 1066, when English society became trilingual. The mass of the population spoke the Old English vernacular2; Latin remained the language of religion and education; and French became the language of the court and socially privileged circles. Gillian Adams’ (1998) research on medieval literature for children focuses entirely on texts in Latin, whereas the collection reproduced in Daniel T. Kline’s Medieval Literature for Children (2003), although consisting largely of Latin texts, includes several in French. One of the texts Kline reprints, the Tretiz of Walter of Bibbesworth, is a French-language textbook in verse composed before 1270 for the Duchess of Pembroke, so that she could teach her family the French required of the medieval English nobility. French was also, of course, the original language of Anglo-Norman romances such as Gui de Warewic to be discussed in the next chapter.

By the mid thirteenth century, after some two hundred years of French rule, the Anglo-Normans were relinquishing control of British territory, and English began to appear in official documents. French usage gradually declined in the upper echelons of English society, although a close relationship with French culture ensured the predominance of translated French romances and courtesy books. Latin continued to play a major role in education as increasing numbers of children from more prosperous families took advantage of the ‘grammar’ schools endowed by benefactors across the country. From the end of the fourteenth century onwards, children were taught in English in the elementary stage of their education, while those who moved on to the grammar school at the age of eleven or twelve began to study Latin seriously. This gave rise to the publication of dual-language textbooks in Latin and English and the practice of translating or ‘construing’ Latin texts by pupils attending grammar schools. Educated children became practised translators in a tradition that continued, at least in private schools, well into the twentieth century.

A continuation of close cultural ties with France and the use of Latin as a base language in educational practice resulted in the dominance of these two languages in source texts translated into English for didactic purposes. Courtesy books, religious, and school texts constituted the reading matter sanctioned by parents, tutors, or schoolmasters throughout the medieval and early modern periods. Fables, too, with their inherent duality as stories with lessons, frequently appeared in Latin and English in schoolbooks. Many translations of Aesop’s fables were designed to maintain the interest of young readers while serving a pedagogical, religious, or political purpose. To illustrate translators’ didactic intentions in rendering French and Latin texts into English across the early modern period, this chapter will introduce a translation of a courtesy book from French by William Caxton; translations of school editions of Aesop’s fables; the seminal translation of Comenius’ illustrated Orbis Pictus by schoolmaster Charles Hoole; and versions of Aesop designed to secure the religious affiliation of young readers. Unlike many of their contemporaries, translators who had an educational mission or a political axe to grind had no wish to remain anonymous, and expressed their intentions in the translators’ prologues or prefaces that form the basis of this chapter.

William Caxton as Translator

It is a little-known fact that William Caxton, best known as the founder of the first British printing press close by Westminster Abbey in the late fifteenth century, was a prominent translator. According to his own account in the afterword to a translation from the French of Raoul Lefèvre’s Recuyell of the Histories of Troy (completed in 1471), Caxton only took the decision to learn the new German craft of printing because demand for manuscripts of entertaining stories was proving to be too taxing for his ‘weary’ hand and ‘worn’ pen (Painter, 1976: 53). Caxton had enjoyed a productive time as a translator under the patronage of Margaret of Burgundy, sister to Edward IV, and eventually retired from his role as representative of the king and English merchants in the Low Countries to devote himself to printing and translating. As translator of The History of Reynard the Fox (1481) and Aesop’s fables (1484)—both of which gradually became children’s favourites and will be discussed in the next chapter—a schoolbook, and a courtesy book for young girls, he fully deserves a prominent place in this history.

‘Courtesy’ or ‘conduct’ books were treatises on the acquisition by children and young people of social manners and moral virtue. Kline’s Medieval Literature for Children (2003) includes a section on such courtesy and conduct literature including Evans’ edited extracts from one of the best-known courtesy books, The Babees Book (c.1475), where the unknown translator of the Latin original comments as follows:

Children, the translator insists, should learn courtesy and virtue in the ‘comvne langage’, English, a policy that Caxton also pursued. Indeed, after printing both a Book of Curtesye (1477) in English verse and John Lydgate’s English translation of a Latin book of table manners by Bishop Grosseteste of Lincoln, Stans puer ad mensam (1478), Caxton himself translated a French conduct book, The Book of the Knight of the Tower in 1484. Geoffrey de la Tour Landry, author of the late-fourteenth-century source text, couched his advice to adolescent girls in a chivalric setting and, like many authors of courtesy books, went beyond etiquette to address religion and ethical matters. Caxton’s

prologue informs readers that he has translated the book ‘in to our vulgar englissh’ at the request of a lady with several daughters, with the intention of supplying them with a manual of appropriate behaviour at all stages of life: ‘techyng by which al yong gentyl wymen specially may lerne to bihave them self virtuously as wel inm their vyrgynyte as in their wedlock y wedowhede’ (de la Tour Landry, ed. Offord, 1971: f. 1 recto).

De la Tour Landry teaches by example. Inspired by the sight of his daughters on a spring day in the garden, the narrator Knight illustrates good and bad models of female conduct in a series of stories incorporating advice on that most intricate set of behaviour patterns, courtly love. Narratives of this kind were surely more palatable to young women than an unadorned set of instructions, especially since—according to editorial material by Offord who has examined both source and target texts—Caxton generously abbreviated some of the lengthy moralising passages in one of the earliest instances of a translator adapting a text for a young audience3.

Caxton also translated a schoolbook dedicated to the youth of London. George Painter’s biography traces four printings by Caxton of a Latin school text known as the Distichia, a collection of moral couplets in hexameters to which the name Dionysus Cato became attached, probably by analogy with the ascetic and just Cato of ancient Rome. The first three editions Caxton printed were of the English verse translation by Benedict Burgh, but the fourth was his own version. For Cato IV (1483–4), as it became known, Caxton took as his source text a dual-language edition in which the Latin verse was also rendered in French prose (Painter, 1976). In his dedication of the book to the City of London, Caxton commends the Distichia as ‘in my judgement it is the best book to be taught to young children in school’, then adds a curious complaint at the moral weakness to which most city children succumb in later life: ‘fairer nor wiser nor better bespoken children in their youth be nowhere than be here in London, but at their full riping there is no kernel nor good corn founden but chaff for the most part’ (cited in Painter, 1976: 137–8). He later qualifies this attack on the decadence of city folk and, as Painter suggests, Caxton’s disparaging remarks may well have been a political manoeuvre connected to the Mayor of the City of London’s support for the usurper Richard III. Nevertheless, such cynical comments on adult citizens indicate a sympathetic attitude to the as yet untainted young people for whom Caxton translated Cato IV and the Knight of the Tower in quick succession, just before beginning work on the fables of Aesop4.

Translating Schoolmasters: Grammarians William Bullokar and John Brinsley, and the ‘Orbis Pictus’ of Charles Hoole

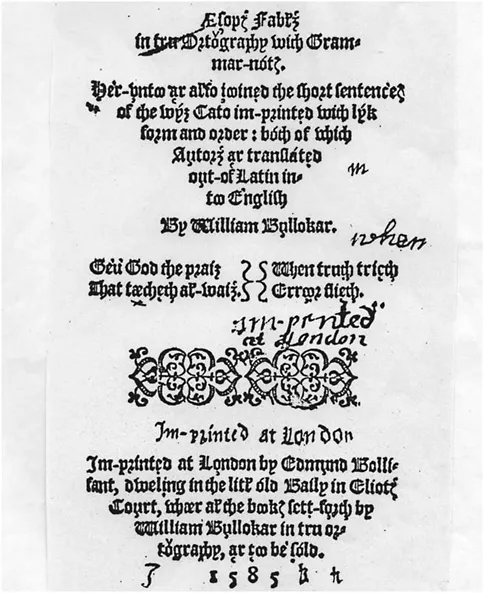

Translators working directly for a child audience in the early modern period were primarily concerned with pedagogical matters. William Bullokar’s translation from Latin of Aesop’s fables, together with ‘the short sentences of the wyz Cato’—the same distichs that Caxton had translated—appeared in 1585. As the title Aesop’s Fablz in tru Ortography with Grammar-notz, suggests, Bullokar, a sometime schoolmaster and soldier, was a zealot in matters of spelling and grammar. Five years earlier he had published a proposed reform of the English spelling system ‘for all learners’ in the Book at Large (1580), which he then exemplified in his translation of Aesop. Bullokar had found the teaching of literacy in the English language frustrating because of the irregularity of links between letters and sounds, a problem that continues to tax primary school teachers to this day. His reform consisted of the extensive use of diacritical marks to indicate pronunciation. One wonders what young readers made of Bullokar’s daunting ‘tru Ortography’ (see Figure 1.2).

Bullokar’s preface to the fables is entirely devoted to orthography and grammar, but he was also determined that pupils should become linguists. In A Short Introduction or Guiding (1580), a publication preceding and summarising the Book at Large, he argues that knowledge of English grammar will enable children to become familiar with other languages:

Bullokar’s aim that children should know the structure of their own language before the age of six in order to understand ‘the secrets’ of other tongues is ambitious, but demonstrates a commitment to the learning of foreign languages that many would applaud today.

Renowned schoolmaster John Brinsley (baptised 1566, died c.1624) also emphasises the learning of written language and grammar in his translation of Aesop from Latin, as his title suggests: Esops fables translated both grammatically, and also in propriety of our English phrase; and, euery way, in such sort as may be most profitable for the grammar-schoole. Brinsley’s dedication of the translation to Sir John Harper expresses an intention that his translation of the fables will teach even the youngest children to embrace learning and wisdom and ‘to bee ashamed of mis-spending their precious time in play and idle vanities’ (Brinsley, 1624: A3). Brinsley was insistent that the emphasis in translation should primarily be on grammar and syntax and only secondly on style. Nonetheless, a prefatory note ‘to the painefull Schoolmaster’ advises that pupils should appreciate the fables as stories and ‘make a good report of the fable, both in English and Latine, especially in English’ (1624: A5). Brinsley is keen to allow for some individuality of interpretation, and one can imagine his young pupils performing these ‘reports’ or retellings in the schoolroom. Margaret Spufford discovered evidence of such a practice, carried out in a lively and competitive manner, in the preface

to the seventeenth-century chapbook The Wise Mistresses, where ‘that rare and learned Scholar Aesop’ is praised for fables ‘which being composed with such incomparable and acute Wit, Jeast and Merriment, that each Scholar daily strove who should outvie the other in the dispute and Rehearsal of them’ (Spufford, 1997: 57).

Seventy years after the appearance of Brinsley’s translation of Aesop, the English philosopher John Locke echoed Brinsley’s emphasis on story and placed a lasting seal of approval on the pedagogical value of the fables in his influential treatise Some Thoughts Concerning Education of 1693. Locke recommends a playful and ‘gentle’ approach to the teaching of reading by means of the introduction to the child of ‘some easy pleasant book. … wherein the entertainment that he finds, might draw him on . … To this purpose I think Aesop’s Fables the best, which being stories apt to delight and entertain a child, may yet afford useful reflections to a grown man’ (1964: 113). The format of a series of self-contained short texts was easily adaptable for school use, especially since fables taught a variety of lessons on practical cunning and intelligence that allowed the translator or reteller considerable licence to adapt and adjust messages to conform to contemporary ideologies on child education. What makes Locke’s advice so radical is the notion that the child’s ...