1

Introduction

“L’Europe s’est déplacé pour voir des marchandises”:1 so commented the critic Hippolyte Taine in 1855, the year of the first Paris Exposition, and four years after the one at London’s Crystal Palace which had started an international trend. The remark encapsulates the significance of the momentous changes in the scale and forms of commercial activity which had begun to take place at this time. No longer do goods come to the buyers, as they had done with itinerant hawkers, country markets or small local stores. Instead, it is the buyers who have taken themselves to the products: and not, in this case, to buy, but merely to “see” the things. In the late 1960s, Guy Debord wrote forcefully of the “spectacle de a marchandise.” crystallizing the way that modern consumption is a matter not of basic items bought for definite needs, but of visual fascination and remarkable sights of things not found at home.2 People go out of their way (se dé-placer) to look at displays of the marvels of modern industrial production: there is nothing obviously functional in a tourist trip. And these exotic, non-essential goods are there to be seen by “tout le monde”: no longer are luxuries a prerogative of the aristocracy. The great glass edifice of the Palace gives open access to all and marks the beginning of what would become, in one of the catch-phrases of the latter part of the century, “la democratisation du luxe.”

The grand buildings of the Universal Expositions, which took place in different cities of Europe and the United States every few years after Crystal Palace, bear a striking architectural resemblance to some more everyday “palaces of consumption.” Department stores developed over the same period. Like the exhibition palaces, they utilized new inventions in glass technology, making possible large expanses of transparent display windows. Visibility inside was improved both by the increase in window area and by better forms of artificial lighting, culminating in electricity which was available from the 1880s. Glass and lighting also created a spectacular effect, a sense of theatrical excess coexisting with the simple availability of individual items for purchase. Commodities were put on show in an attractive guise, becoming unreal in that they were images set apart from everyday things, and real in that they were there to be bought and taken home to enhance the ordinary environment.

The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a radical shift in the concerns of industry: from production to selling and from the satisfaction of stable needs to the invention of new desires. The process of commodification, whereby more and more goods, of more and more types, were offered for sale, marks the ascendancy of exchange value over use value, in Marx’s terms. From now on, it is not so much the object in itself —what function it serves—which matters, as its novelty or attractiveness, how it stands out from other objects for sale. The commodity is a sign whose value is derived from its monetary price relative to other commodities, and not from any inherent properties of usefulness or necessity.

In France, the department store can be dated from virtually the same moment as the first Great Exhibition in London: the year 1852, when Aristide Boucicaut took over the Bon Marché. During the first eight years of his ownership turnover increased tenfold, and it went on rising at a comparable rate through the subsequent decades. The model was copied by other stores in Paris (Le Louvre, La Belle Jardinière, Le Printemps, Le Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville, and others), in provincial cities and in other countries: Whiteley’s and Harrods of London, Macy’s of New York, Wanamaker’s of Philadelphia, Marshall Field and The Fair in Chicago, and so on. Within a very short period, department stores had been established as one of the outstanding institutions in the economic and social life of the late nineteenth century; and together with advertising, which was also expanding rapidly, they marked the beginning of presentday consumer society. Stores, posters, brand-name goods, and ads in the daily and magazine press laid the groundwork of an economy in which selling and consumption, by the continual creation of new needs and new desires, became open to infinite expansion, along with the profits and productivity which lay behind them.

Some of the specific innovations which distinguished le nouveau commerce, as it was called, from the old have been outlined above. Grandiose architecture and theatrical forms of lighting and display contributed to a blurring of both functional and financial considerations, and other factors reinforced this effect. First, the inclusion of (potentially) every kind of object under the same roof removed the categorical distinction between different retailing specialities: the only characteristic unifying the goods in the store was that they were all for sale. Also, the client on her way from one department to another might well be attracted in passing by something which she had no previous intention of acquiring. “Impulse buying” replaced planned buying; or rather, as the chapter on Zola’s Au Bonheur des Dames will show, the existence of such supposedly natural, irrational urges in customers was actually the result of a rigorously rational entrepreneurial scheme.

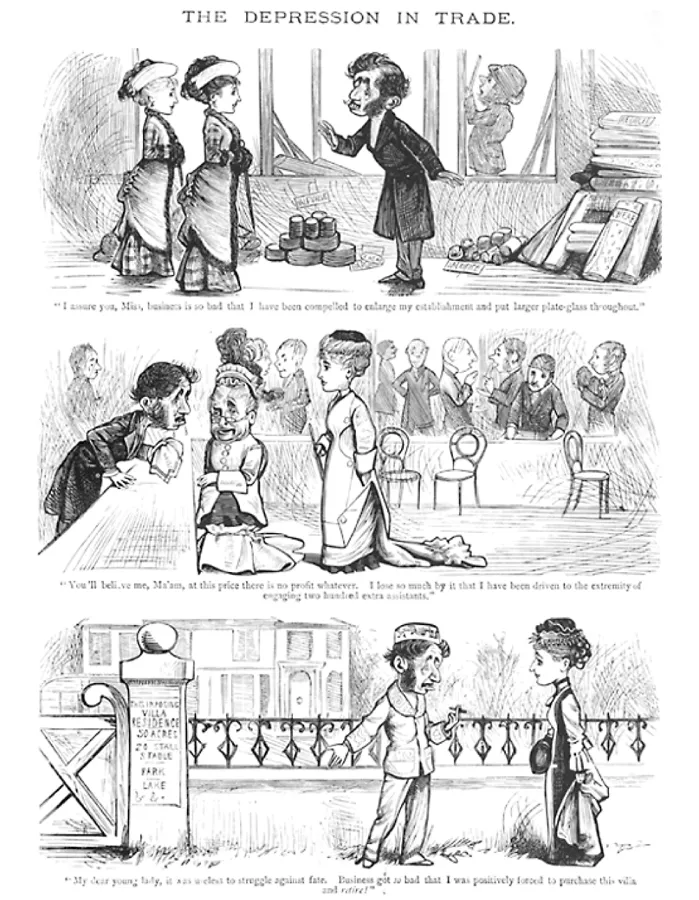

The principle of entrée libre or open entry did away with what had previously been a moral equation between entering a shop and making a purchase. At the same time, a fixed price policy, supported by clear labelling, put an end to the conventions of bargaining which focused attention on shopping as paying. Assistants in department stores received commissions on sales, so were inclined to be flattering rather than argumentative: the customer was now to be waited on rather than negotiated with and money, in appearance, was not part of the exchange (particularly since paying in fact took place in a separate part of the store). People could now come and go, to look and dream, perchance to buy, and shopping became a new bourgeois leisure activity—a way of pleasantly passing the time, like going to a play or visiting a museum. Stores became places where customers could even spend an entire day, since they were supplied with amenities ranging from reading rooms to refreshments to toilets—perhaps their nearest approach to basic use value. Thus the fantasy world of escape from dull domesticity was also, in another way, a second home. This combination would also tend to reinforce the potential for crossing the boundaries between looking and having: the real home could be made more of a fantasy place, the real woman more of a queen, just as the fantasy store was a place where she felt at home and enjoyed the democratic privilege of being treated like royalty.

All this is far enough from the steady serviceability of old-fashioned commerce. Perhaps most significant of all, the prix unique or fixed price also stood for cheapness, since rapid turnover of stock enabled the grands magasins to undercut their competitors with low profit margins. As Georges d’Avenel put it in 1894, “It seems that sales breed sales, and that the most diverse objects, juxtaposed in this way, lend each other mutual

support.”3 With the advent of the department store, selling takes on a life of its own, independent of the objects with which it deals, and by the same token, “shopping” as a distinctive pursuit has no inherent connection with the procuring of predetermined requirements.

In the shift to consumer capitalism, then, modern commerce engages in a curiously double enterprise. On the one hand, a process of rationalization: the transformation of selling into an industry. The department stores are organized like factories, with hundreds of workers, shareholding companies, vast turnovers, and careful calculation of continual strategies of expansion. On the other hand, the transformation of industry into a shop window. This massive and revolutionary extension of scope is achieved by the association of commerce with ideological values that seem to be diametrically opposed to the mundane actuality of work, profits and rationality. The grands magasins, like the great exhibitions, appear as places of culture, fantasy, divertissement, which the customer visits more for pleasure than necessity.4

The transformation of merchandise into a spectacle in fact suggests an analogy with an industry that developed fifty years after the first department stores: the cinema. In this case, the pleasure of looking, just looking, is itself the commodity for which money is paid. The image is all, and the spectator’s interest, focused from the darkened auditorium onto the screen and its story, is not engaged by the productive organization which goes to construct the illusion before his/her eyes, nor with any practical use for the viewing experience. In the way it appears, the Hollywood “dream factory” necessarily suppresses

its mechanical, labored parts, and works against any notion of stable need by providing something characterized by its very separation from the relative ordinariness of everyday life.5

The dominance of signs and images, the elements of pleasure, entertainment and aesthetic appeal indicate what the new large-scale commerce shares with practices derived not from industrial production, but from the arts. Yet if industry, through the shift to selling techniques involving the making of beautiful images, was becoming more like art, so art at this time was taking on the rationalized structures of industry. In the period before cinema, the cultural industry par excellence, this is true most of all in the case of literary production.

The massive increase in book and journal output during the nineteenth century responded in part to a real change in market conditions: the increase in population and literacy. At the same time, reading became generally a private, domestic occupation, and one involving short-term rather than durable goods. These conditions implied a high volume and fast turnover of products, both of which were made possible by advances in technology and transport. More than at any time since the invention of printing and the beginnings of the first commodified literary genre, the novel, printed matter in general was becoming just another “novelty” to be devoured or consumed as fast as fashions changed. Production might in extreme cases be systematized to the extent of New York’s “literary factories” which produced a regular quota of “written-by-the-yard” novels commissioned out to a list of competent workers.6 In general, the rationalization of the publishing industry radically modified the status of writers, now greatly increased in number in proportion to the rise in output.

It is no coincidence that the “romantic genius” of the early part of the century came trailing his clouds of glory into the world at precisely the historical moment when the industrialization of literature could be read as a fatal compromise of his authorial freedom. Poetic genius pitted itself against the mechanical demands of an all-too-workaday commercial world, and neither side of the dichotomy, put this way, can be thought apart from the other. The same developments which were binding commerce and culture closer together, making commerce into a matter of beautiful images and culture into a matter of trade, a sector of commerce, also, paradoxically, led to the theoretical distinction whereby they were seen not just as heterogeneous terms but as antithetical in nature. The “absolute” value of “art for art’s sake” versus the monetary values of commerce became a standard opposition in contemporary debates, and the difference between “authentic” and “enslaved” literary labor became a lived contradiction for working artists and writers throughout the century.

Naturalist novels stand at the crossroads of these concerns. Of the main genres of literature, itself the most industrialized of the arts, the novel was by far the most significant in terms of sales and the most systematically organized in its production and distribution. In the case of poetry, which was restricted to a limited readership of a certain class, and whose sales were rarely enough to pay the author a living wage, questions of the market were relatively insignificant. Poetry, as a result, could be identified as a place kept pure, the locus of “art for art’s sake,” uncontaminated by the profit motive or by the vulgar requirements of the popular market. In practice, only those with independent means of support could devote time to writing poetry; while scribblers of novels had their pages blotted both by the pressure to earn and to sell, and by the flimsy associations of something read predominantly by women with nothing different to do.

In refusing the theoretical opposition between art and the modern world, naturalists challenged the usual assumptions directly. Instead of the otherness of poetry, or the idealizing and moralistic tendencies of sentimental fiction, they took as their subject contemporary society, with all the qualities from the mundane to the brutal which allegedly made it incompatible with art Technically, also, they adopted an explicitly modern method and language. Their work was researched as thoroughly as a sociologist’s, and recorded for the most part in an objective, impersonal language. The period of naturalism (1880–1920, approximately) is contemporary with the rise of the social sciences, and there are significant parallels between the two practices. Their common project of showing the “facts” of society in a plain, unembellished form marked off naturalism as radically inartistic in the established sense, in which science and art were considered two poles as different from one another as machines from feelings.

In terms both of their place in the field of literary production, and of the methods and subjects which they took on, naturalist novels are thus on the borders between art and industry, which makes them a priori a promising ground for considering questions of commerce and culture in the late nineteenth century. These questions are also addressed directly and implicitly within the novels themselves, where they occur as part of the social reality which the novels seek to reproduce. Inside and outside the texts, then, these novels provide a way of exploring how such facts and values and changes are articulated into socially meaningful forms.

An issue which arises at every point is that of gender. Women’s contradictory and crucial part in “the oldest trade in the world”—at once commodity, worker and (sometimes) entrepreneur—can be taken as emblematic of their significance in the modern commercial revolution. This is drawn out by a suggestive passage of Walter Benjamin’s essay “Paris, capital of the nineteenth century” describing Baudelaire’s dialectical images of “the ambiguity attending the social relationships and products of this epoch”:

From the point of view of the f...