1

INTRODUCTION

Magic in ancient Greece

J.C.B.Petropoulos

The Greek word μαγεία comes from the Old Persian makuç, originally a member of an ancient Median tribe or clan which became specialized in religious functions. St Matthew, as many of us know, recognized that the Magoi (in Greek) were competent astrologers intimately familiar with the sky. But well before the Christian era, Herodotus revealed the members of this γένος to be carrying out, in 480 BCE, actions which in other classical and post-classical sources are often called γοητεία, , μαγγανεία or even μαγεία: if Herodotus is to be believed, these men performed unspecified on the Strymon River in Thrace and slightly later appeased blustery winds off the coast of central Greece by chanting spells .1 Magic, however, was hardly a Persian import. Its origin dated to unknown times in the Greek world and it was largely the province of local men and women. By the time of Heraclitus (c. 500 BCE) male practitioners might be called μάγοι2 but more often, at least in the case of itinerant professionals, they had other names, such as γόης, μάντις or αγύрτης. In Chapter 4, Sarah Iles Johnston explores the death-related activities of this exclusively male occupational class. If magic was not late, neither was it peripheral to archaic, classical and later Greek society. As David Jordan and others have recently shown (see Chapter 2), while Plato was expounding his (rather peripheral) philosophical religion, mainstream Athenians were cursing their neighbours through magical means. In time, from the Hellenistic period onwards, magic became more and more elaborate and ‘syncretic’, borrowing much from Eastern mystery religions and especially Near Eastern and Egyptian lore, as William Brashear shows in Chapter 6.

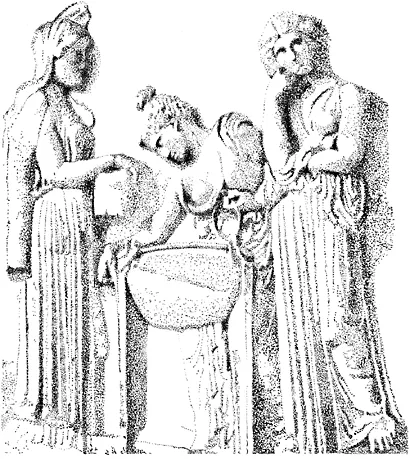

How, in general, did the ancients’ magic work? For one thing, it operated outside the sphere of public, or polis, religion; it was always private and usually had the character of mystery, or secret, cultic practice. Second, it mobilized, manipulated or even occasionally coerced the demons of the dead or certain (usually underworld or chthonic) gods, and it did so in an automatic, mechanical manner. Magic, in other words, normally lacked the element of χάρις—of reciprocity; hence the notions of supplication or vow were absent or extremely rare in, say, defixiones . Gods and demons were either Figure 1 Medea, assisted by two maidservants, prepares her rejuvenating drug in a cauldron. Roman copy of a relief by Alkamenes (5th century BCE). Rome, Vatican Museums.

commanded or otherwise ‘induced’ (Plato uses the ambiguous term )3 to carry out the spell-operator’s invariably selfish acts. These acts were meant to be either harmful (‘black magic’, which Circe works at first; see the discussion by Nanno Marinatos in Chapter 3) or beneficent (compare the medicinal effects of a number of magical gems, as examined by Arpad Nagy in Chapter 7). Because of its destructive potential (which even Plato allowed),4 and also because it worked outside the polis, often reversing civic religious rituals and ideas, magic was definitionally an anti-social activity in the Graeco-Roman world. Perhaps, as Brashear and Iles Johnston demonstrate, the driving force behind magic in general was the and the frustrations engendered in an agonistic, competitive society. What is more, a number of laws and other texts which date from the early fifth century BCE onwards and which proscribe magical acts show that the Greeks and Romans regarded this phenomenon as a potentially harmful subset of religious activity. Yet despite its alleged anti-social ‘marginality’, magic formed the penumbra or background of much high literature and even of the visual arts. It is quite probable, as Antonio Corso argues in Chapter 5, that Praxiteles himself and other sculptors used magical processes to create lifelike, seductive statues of mortals and gods.5 Indeed, now our own ‘rational’ twentieth century has drawn to a close, it is high time we remembered that the ancient Greeks’ legacy to Western culture was not only democracy and rational enquiry, but also numerous magical beliefs, practices and figures such as the medieval and modern witch and warlock.6 Whether or not it is true, as the anthropologist M.Winkelman has argued,7 that magical traditions generally have a serious basis in parapsychology, the study of Greek and Roman antecedents is a vast and compelling chapter in the history of religion and society. Wilamowitz put it well: He was eager, he said, to study Greek magic ‘in order to understand my Hellenes, to be able to judge them fairly’.8

Notes

1 Hdt. 7. 113–14; 191. The term μαγεία is first attested in a dismissive sense in Gorgias DK 82 B 11, 10 ; but in Thphr. HP 9. 15. 7 the plural , is used in a neutral sense for ‘magic’. 2 Heracl. DK 12 B14 employs the term πάγοι (in the plural) in a pejorative sense suggestive of a charlatan as do Soph. (OT 387 μάγον…μηχανορράφον) and other authors. The plural form μάγοι may be attested in a positive, technical sense in the Derveni Papyrus, dating from the late fourth century BCE.

3 Rep. 364 B-C; Laws 10. 909 B.

4 Rep., loc. cit.; Laws, loc. cit.; however, at Laws 11. 933 B Plato is uncertain about this potential.

5 Picasso is reported once to have performed a quasi-magical ceremony before moulding clay. He also talked of his creative powers in magical or near-magical terms. See Berger 1965: 99–101; cf. also below, Ch. 23.

6 For instance, since L.Spohr’s Faust of 1815 (based on the Faust legend but ultimately in large part on Graeco-Roman sorcery), about sixty-five operas on the same theme have been composed. Romantic literature and ballet also abound in related themes.

7 Winkelman 1982.

8 Von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf 1931: 10.

2

THE ‘WRETCHED SUBJECT’ OF ANCIENT GREEK MAGIC

David jordan

Over fifty years ago, the English scholar E.S.Drower published a careful edition of the Mandean ‘Book of the Zodiac’. Shortly afterwards, it was reviewed in the American journal Isis by George Sarton, then the doyen of the history of science, who described the book as ‘a wretched collection of omens, debased astrology, and miscellaneous nonsense’. In the next issue of that journal Otto Neugebauer, the historian of ancient astronomy, wrote a reply ‘to explain to the reader why a serious scholar might spend years on the study of wretched subjects like ancient astrology’.1

Neugebauer pointed to the work of such great men as the Belgian Franz Cumont, who assembled a distinguished international group of philologists to produce the monumental Catalogus codicum astrologorum graecorum (Brussels, 1898–1936).

The often literal agreement between the Greek texts and the Mandean treatises requires the extension of Professor Sarton’s characterization to an enterprise which has enjoyed the whole-hearted and enthusiastic support of a great number of scholars of the first rank. They all laboured to recover countless wretched collections of astrological treatises from European libraries, and they succeeded in giving us an insight into the daily life, religion and superstition, and astronomical methods and cosmogonic ideas of generations of men who had to live without the higher benefits of our own scientific era.

Indeed, the astrological manuscripts are better than any other source for the intimate details of the transmission of ancient astronomical concepts (Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian) and of their survival to present times.

Shortly after Neugebauer’s reply, Alfons Barb, himself then the doyen of the study of ancient magic, wrote a thoughtful analysis of this disdain. He had begun his career as a specialist in the Roman archaeology of his native Austria. Rather early on, in 1925, he published a small, fragmentary scroll consisting of two inscribed thin metal sheets, gold and silver, rolled up inside one another. It had been found in a grave and dates probably to the third century CE. The silver sheet had a Greek text: ‘For migraine: Antaura came out of the sea, cried aloud like a deer, shouted out like a cow. Ephesian Artemis met her: “Antaura, where are you going?” “Into Headache.” “Don’t [go] to into []”’.2

The little scroll is what the ancients called a phylakterion (from the verb phylassô, protect), which would have been worn by the deceased in his or her life-time as a protection against headache. The text is part of a story preserved, in slightly different form, in a sixteenth-century manuscript produced in southern Italy:

‘Migraine’ prayer against headache: Migraine came out of the sea, crying (?) and bellowing, and our lord Jesus Christ met it and said: ‘Where are you going, migraine and headache and eye-ache and inflammation-of-the-breath and tears and inflammation-of-the-cornea and dizziness-in-the-head?’ And headache answered our lord Jesus Christ: ‘We are going to sit on the head of the slave of God so-and-so’. And our lord Jesus Christ says to him: ‘See that you don’t go into my slave, but flee and go into the wild mountains and enter the head of a bull, there to eat meat, there to drink blood, there to destroy eyes, there to addle the head, to harm, to destroy. And if you disobey me, there I shall destroy you in the burning mountain, where dog bays not and cock crows not’. Thou who set the mountain in the sea, set migraine and pain to the head, the forehead, the brows, the brain of the slave of God so-and-so.3

This phylactery and the ‘migraine prayer’ and the long search to document their background in folk belief were to play a major role in Barb’s own development as a scholar. He was a deeply religious man, a practising Roman Catholic. In the Hitler years, he settled in London, where he eventually found a post as librarian at the Warburg Institute, itself long a centre for the study of the ‘wretched subjects’ that Neugebauer had defended. With such bibliographical resources now at his disposal, he produced an article that will remain a classic for the study of Christian iconography,4 in which he shows, somewhat contra exspectationem, that the imagery of certain representations of the Virgin Mary can be traced back to that of the headache demon Antaura who rose from the sea. His years of research gave him a valuable perspective; a result was his own analysis of the opposition to the study of what Sarton had called ‘miscellaneous nonsense’.5

One of Barb’s specialties within the study of magic was the ‘Abraxas’ or the ‘gnostic’ gemstone.6 Throughout the Renaissance these semi-precious stones were avidly collected. The year 1657 saw the publication in Antwerp of a book that did much towards providing a scientific basis for their study, the Abraxas seu Apistopistus of J.Chiflet and J.Macarius (L’Heureux). Those were the days, Barb wrote, before Humanism was replaced by Classicism.

The disappearance of the o...