1 The port of Osaka

From ancient times to today

Towao Sakaehara

Evolution of the port of Osaka

From ancient times to the sixteenth century, Nara and Kyoto formed the Japanese capital. These two cities were then the country’s political, economic, transport and cultural centers. The capital was subsequently transferred to Edo, or Tokyo as we know it today, and remained there until this day. The fortunes of the city and of the port of Osaka have strongly been influenced by the transfer of the capital.

The history of the city and the port of Osaka can roughly be divided into four stages (Table 1.1). The first stage is from the fifth to the eighth centuries, which corresponds to the periods of the Wa Dynasty, Asuka, and Nara eras. The port of Osaka was then called the port of Naniwa-zu and was under the direct control of the great king. The second stage is from the ninth to the sixteenth centuries, corresponding to Heian, Kamakura, Nanboku-cho, (Northern and Southern Court), Muromachi, and Sengoku (Age of Civil Wars) period. During the third stage, i.e. the Edo period from the seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth century, the port of Osaka played a central role in the country’s market economy. And last, the fourth stage is from the second half of the nineteenth century until today, corresponding to the eras of Meiji, Taisho, Showa, and Heisei.

In this report, I would like to discuss the city and the port of Osaka in relation to politics, their significance and the functional roles in the country’s economy and circulation for each of the above-mentioned four stages, with special focus on the ancient times.

Table 1.1 Evolution of the port of Osaka

Naniwa and the port of Naniwa-zu in ancient times

Naniwa in the fifth century

Osaka was called Naniwa in ancient times.1 To understand this period, one should first focus on the great storehouses built in Naniwa.

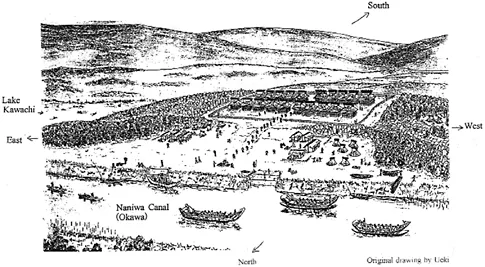

During a large-scale excavation conducted from 1987 to 1990 in Hoenzaka-cho, Kita-ku, Osaka city, large storehouses dating from the second half of the fifth century were discovered.2 Sixteen buildings have been found to date, but there are possibly more hidden in the surrounding area. The amount of floor space per building is 82–98 square meters, which is quite large for the period. These buildings were arranged on a detailed plan.3

Up to now, only the Narutaki storehouses from Wakayama prefecture discovered in 1982 may be considered comparable in size to those in Naniwa.4 These date from the first half of the fifth century and are a little older than those in Naniwa. Seven buildings have been discovered. The amount of floor space per building is 65 square meters on average and although this is quite large for the period, they are smaller than those of Naniwa and their layout is not as detailed. Therefore, we can say that no storehouse from the fifth century exceeding the size of those in Naniwa have been discovered so far.5

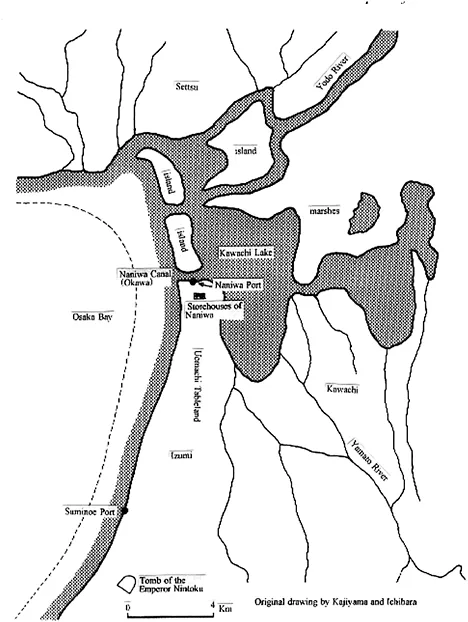

The surrounding landscape is also an important factor for the siting of these storehouses. The geographical features of Osaka then were quite different from those of today. The Uemachi Tableland stretched out from south to north, surrounded by the waters of Osaka Bay and Kawachi Lake (Figure 1.1).6 The storehouses were built on the tip of the Uemachi Tableland, facing the Okawa River, Osaka Bay and Kawachi Lake (Figure 1.2).

There are many questions to be asked about such a large-scale storehouse complex. In this chapter I will discuss two of them, namely, why were they built in the first place and why in Naniwa?

Concerning the first question, I believe that it is related to two important events on the Korean Peninsula.7 First, in 427, King Changsu of Koguryo transferred the capital from Wandu (Ji’an, Jilin Province, China) to Pyongyang. It was part of King Changsu’s policy to extend his power southward. He inherited this policy from his father, King Kwanggaeto, and followed it with vigor.

Second, in 475, King Changsu personally led the army and attacked Hansong, the capital of Paekche. The castle fell and King Kaero of Paekche was killed. It may fairly be said that by this incident, the kingdom of Paekche temporarily went out of existence. (Figure 1.3)

Following these events and especially after the second incident, military tension mounted among the three Korean kingdoms. The seriousness of the situation in the Korean Peninsula came as a great shock for the Wa Dynasty, which had a close relationship with Paekche. The Wa Dynasty, strongly feeling the necessity to be prepared for a military action, built large storehouses in order to keep war supplies.

Figure 1.1 Osaka area in ancient times.

Then, the second question arises: why did the Wa Dynasty choose Naniwa to build the storehouses and not the Tsushima Islands or northern Kyushu which face the Korean Peninsula, or at least in more western regions of Japan? The reason can be found in the project of excavating the canal of Naniwa-no-horie that cut across the northern part of the Uemachi Tableland from east to west.

In Japan’s first two historical chronicles, Kojiki (history of the royal houses) and Nihon Shoki (an official national history), there are descriptions of the excavation of Naniwa-no-horie during the reign of Emperor Nintoku.8 Exactly when the excavation took place remains a controversial issue. It is difficult to determine the precise time using only the above-mentioned descriptions because of problems with the reliability of the records. Since it has been determined archaeologically that the large storehouses were built in the second half of the fifth century, it may be fair to assume that the excavation of the canal, which has strong ties with the storehouses, also took place in the fifth century.

Figure 1.2Restored diagram of large storehouses.

Figure 1.3 Northeast Asia in ancient times.

When the project of excavating Naniwa-no-horie, which also had the aim of flood control, was completed, Naniwa became directly connected with Yamato region, then the center of Japan, through the two major rivers of Yodo and Yamato. The political, military, economic and transportation importance of Naniwa region rose dramatically. Around the same time, the port of Naniwa-zu was established. There are various arguments as to its exact position,9 but here I would like to follow the opinion that it faced Naniwa-no-horie. In that case, one can assume that the port of Naniwa-zu was established following the excavation of Naniwa-no-horie.

Diplomatic missions sent abroad by the Wa Dynasty always departed from the port of Naniwa-zu. Its navy flotillas heading abroad also first gathered here before setting to sea. Considering its geographical position at the eastern edge of the Inland Sea, it is clear that this was the center of water transport for western Japan.

Thus, Naniwa-zu was an important port for the Wa Dynasty throughout ancient times. Until then, Suminoe-no-tsu, located at the southern part of Osaka, was the central port of the Wa Dynasty for military and diplomatic use. Its role as a port was supplanted by the establishment of the port of Naniwa-zu.10

In sum, the three projects described above, namely the construction of large storehouses, the excavation of Naniwa-no-horie and the establishment of the port of Naniwa-zu were undertaken as a set by the Wa Dynasty. In other words, the blueprint of Naniwa was drawn up under the strong initiative of the Wa Dynasty during the second half of the fifth century.

Naniwa in the sixth to seventh centuries

In seventh century Naniwa, there existed different government facilities. In terms of political and diplomatic use, Taigun, Shogun and Murotsumi should be mentioned.

Taigun and Shogun were government facilities for diplomatic functions where official diplomatic ceremonies took place. Similar facilities could be seen in Northern Kyushu. In the case of Murotsumi, there is mention of Naniwa-no-murotsumi (Residence of Naniwa), Mitsuno-karahito-no-murotsumi (Residence of the Visitors from Three Kingdoms of Korea), Kudara-no-marouto-no-murotsumi (Residence of the Visitors from Paekche) and Koma-no-murotsumi (Residence of the Visitors from Koguryo) in historical documents. These were sleeping accommodations for diplomatic missionaries and presumably there were different buildings for each of the three Korean countries (Koguryo, Paekche and Silla). Probably Naniwa-no-murotsumi and Mitsuno-karahito-no-murotsumi are general terms for buildings covering all three countries. Visiting foreign diplomats basically stayed in these facilities and, if their visit required it, continued on to Yamato region, had an audience with the Great King and participated in ceremonies of the imperial court.

The function of Naniwa-zu as a port also persisted after the fifth century, with the same degree of importance as before. Here, diplomatic missionaries, both Japanese and foreign, arrived and departed.

In the second half of the seventh century, the great palace of Naniwa-nagara-toyosaki-no-miya was constructed at the tip of the Kamimachi Tableland. The new government that was formed after the coup of 645 moved its capital from Yamato region, observing the importance of Naniwa. This great palace has been identified as the Early Naniwa-no-miya site, which has been continually excavated for over fifty years since the Second World War.11

There is still not enough evidence to say that there was a kyo12 (residential area) in Naniwa-nagara-toyosaki-no-miya (early Naniwa-no-miya). However, it was equipped with a large group of storehouses. Both the palace and the storehouses were completely destroyed by fire in 686. The aforementioned group of storehouses of Naniwa has been discovered near this site.

Naniwa in the eighth century

In the eighth century, the political system of ritsuryo, a system based on administrative laws, was at its prime, centered in the then capital Heijo-kyo. The previously burnt-down Naniwa-no-miya was rebuilt as a subordinate town to the capital during the 720s...