![]()

1

Making citizenship meaningful in the twenty-first century

Introduction

The Swedish general elections of September 2006 ushered in some dramatic political changes. First, the Conservative (Nya Moderaterna) Party received record high support (26.1%) in the parliamentary election and the Social Democratic Party noted record low support (35.2%), while the five other parties that received between 7.9% and 5.2% of the votes were returned to the Riksdag. Second, the non-socialist parties, known as the Alliance for Sweden, could form a new coalition government with a majority of 178 seats of 349 in the Riksdag. Third, the populist, anti-immigrant party, Sverigedemokraterna (sd), received 2.94%, falling short of gaining representation in the Riksdag,1 but it did get 281 seats in the local elections2 in 144 municipalities, or nearly half of them. Table 1.1 in the appendix shows the results of the Riksdag elections between 1982 and 2006. Some foreign observers now claim that the Swedish electorate has turned its back on the welfare state. However, it is far too soon to claim that this election represents a sharp turn to the right in Swedish politics or that the results threaten the Swedish welfare state.

Reasons for the change of government given by the experts on election night and shortly after reflect several common themes. They include arguments like: the voters wanted a change after 12 years of Social Democratic rule; the Social Democrats and their Prime Minister, Göran Persson, made a tired, weary impression in several of the early debates; the traditional leftist issue of unemployment and work for everyone was abandoned by the Social Democrats, but taken up successfully by the non-socialist parties during the campaign – otherwise, it was hard to see any major difference between the proposals of the right and left, in particular concerning welfare services; the parties forming the Alliance for Sweden developed common policies in many areas and spoke with one voice as a team, in contrast to the Prime Minister, Göran Persson’s solo stance on many questions, with little or no consultations with his government partners, the Leftist and Green Parties; the Social Democrats appeared like proud bureaucrats, but lacked a vision for the future and refused to listen to criticism of many acute problems, etc. The final results were slow coming in and were only available shortly before midnight on Election Day. Soon after the Prime Minister, Göran Persson, announced in a TV interview that he would resign as party chairman and turn over control of the Social Democratic Party to a new chairperson at an extra party congress in March, 2007.

The political pundits, mostly professors of political science, were quick to provide their analysis and make proposals to the new majority on the debate page of the major daily newspaper, Dagens Nyheter. The first proposed that it would be logical for the non-socialist parties in the winning Alliance for Sweden to capitalize on their victory by forming a single party to insure success in the next election in 2010 (Möller, DN, 18/9-06). The second argued that the result put an end to minority governments and political compromise between parties belonging to different political blocks. Majority politics would provide voters with two clear alternatives and could possibly contribute to increasing confidence for politicians (Lewin, DN, 19/9-06). The third declared the election result a triumph for the Social Democrats, since their social model, based on a universal welfare state, gained support from the winning Alliance for Sweden (Rothstein, DN, 20/9-06). Differences between them and the leftist parties in terms of the welfare state were marginal and the non-socialists were forced to embrace it in order to win the election. Elsewhere, the fourth called for the leftists to form a single party to face the united Alliance for Sweden in the next parliamentary elections in 2010 in order to return to power (Blomgren, 20/9, svt.se). However, the chairwoman of the Swedish Federation of Labor (LO) quickly pointed out that the next round of collective bargaining in the Spring of 2007 could be threatened if the Alliance for Sweden pushed through some of its proposals for changing the balance between labour and the employers (Lundby-Wedin, DN, 22/9-06).

In the days following the Riksdag election the final results for smaller parties and local municipal elections became available. Only then did the full scale of the gains for the populist, anti-immigrant party, Sverigedemokraterna become evident. Although they failed to gain seats in the Riksdag they did get representation in 144 municipalities, 45 where they could hold the balance of power between the Alliance for Sweden and the leftist parties. They did particularly well in the south and west of the country, with 22.9% of the votes in Landskrona and 12.6% in Trelleborg. Their support at the national level entitled them to 45 MSEK in public campaign funds starting in 2007. Leaders of the national parties on both sides of the political spectrum quickly stated that they intend to rule at the municipal level without the support of Sverigedemokraterna. However, this may not always prove possible. But, in at least a dozen municipalities where the Sverigedemokraterna gained one or more seats, they may remain unrepresented, as their ballots had no candidates’ names. Several of the write-in candidates appeared unwilling to bear the sd party label or represent it in the municipal council. Thus, some of these seats will remain vacant until the next election in 2010.

Sweden and Swedish politics nevertheless changed dramatically after the 2006 elections. Sweden has now become an ordinary member of the European Union (EU), with an established populist, anti-immigrant party, similar to those found in many other European countries, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany and Norway. Many voices are now calling attention to the failure to cope with such a phenomenon by ignoring it. Isolation failed miserably in Belgium to minimize Vlaams Belang, which now has become the second largest party in some areas.

Fredrik Reinfeldt, Chairman of the Nya Moderaterna or Conservative Party repeatedly claimed during the 2006 election debate, shortly after the election results became known, and again in his government’s declaration of intent at the opening session of the new Riksdag, that many voters felt a deep sense of frustration due to their exclusion (utanförskap) in Sweden today. There are, of course, several indicators of growing voter disenchantment with liberal representative democratic institutions and a growing feeling of powerlessness among the electorate. Long-term trends in declining voter turnout, sharply decreasing membership levels in political parties, growing distrust of politicians and support for populist, anti-immigrant parties are but a few ominous signs, found not only in Sweden, but in other established European democracies. Many voters in Sweden also experience a growing feeling of exclusion both as employees and users of public services, due to the lack of control over their work conditions and/or the quality of major welfare services. As employees they have little say about the what, when, where and how of their daily activities as providers of public welfare services. As users they have little say about the quality of the public services provided in their name. Standardization and equality of access to public welfare services are central values for the Social Democrats and often interpreted as the provision of homogeneous public welfare services everywhere in the country, with little room for alternatives. How will the Conservatives and their coalition partners that took over the reigns of government at the beginning of October, 2006 attempt to channel these feelings of frustration and exclusion? Whether they can harness them to develop and promote a new architecture for the welfare state, without launching major cutbacks and massive privatization of public welfare services, remains to be seen.

A major reason for the growing feeling of exclusion, in politics, at work and/or as a user of public welfare services is the lack of control or influence in such matters. The growth of large bureaucracies, both in the public and private sectors, provide an important factor contributing to the growth of feelings of exclusion by citizens and their experience of powerlessness as voters, workers, users of public services and taxpayers. One main remedy for such feelings of exclusion and lack of control is, therefore, to promote greater citizen influence in important matters of daily life in politics, at work and in the provision of welfare services. One of the main arguments found in this book is that a possible solution to the growing feelings of exclusion by voters, workers, users of public services and taxpayers is found in small-scale provision of welfare services. Then each individual’s contribution is important and visible; it makes a notable difference and therefore gets recognition. Replacing big public organizations by big private firms, either national or multinational, will do little to alleviate the growing feelings of exclusion by ordinary citizens. Replacing public provision of welfare services with private for-profit providers in the name of greater ‘freedom of choice’ will, at best, provide a temporary illusion of greater influence for some citizens. Others are likely to reject it for ideological reasons. Choice between different providers of welfare services may be necessary, but it is not sufficient to give ordinary citizens greater influence. Only their direct participation in the provision of welfare services will give them substantial influence and resolve their growing feelings of exclusion as voters, workers, users of welfare services and taxpayers. This can be achieved by contracting out the provision of welfare services to third sector providers.

Democratically controlled and run voluntary associations, cooperatives and social enterprises in the third sector received no attention in the 2006 Swedish election debate. Yet, many recognize their potential contribution to alleviating citizens’ feelings of exclusion and to reorganizing the welfare state. However, the importance of the dramatic political changes in the 2006 election for the third sector or the social economy remains highly uncertain. On the one hand, it could result in positive changes that imply greater pluralism and flexibility in the provision of welfare services, including greater third sector provision. On the other hand, it could prove mainly negative and merely result in replacing the state provision of welfare services by the market. In the latter case the domination of municipal providers would be replaced by the domination of multinational companies noted on the stock market in Stockholm and elsewhere. This would leave little room for third sector provision, or for voter, worker, user and/or taxpayer influence in determining the what, when, where and how of providing welfare services.

The relation between different service functions and the sectors providing welfare services is hotly contested. By service function I am referring to a distinction between the financing, provision and supervision of welfare services. The sector providing a welfare service can either be the public sector, usually through a local or regional authority, a third sector organization or a private for-profit firm. For ideological reasons some maintain that the public sector should combine all three functions and provide all welfare services, since it alone can promote equality between citizens. Others claim that the market is best suited to provide most or all welfare services since it alone promotes the efficient use of public funds. A middle or third position argues that the third sector should provide many welfare services, since it alone can promote greater welfare pluralism, a rejuvenation of the welfare state and greater citizen participation in the provision of welfare services.

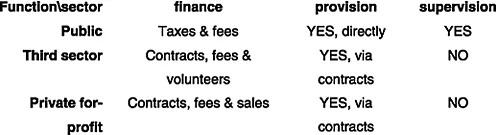

Leaving these ideological positions aside, these three functions and sectors can be combined in the following fashion. The public sector can finance the provision of welfare services through taxes and user fees, the third sector through contracts, user fees and volunteers, and the private for-profit sector through contracts, user fees and even sales. All three sectors can provide

welfare services to citizens, but in a different fashion. The public sector provides welfare services directly to citizens, while both the third sector and the private for-profit sector provide them via public sector contracts. Turning to supervision of welfare services, at present only the public sector has the authority to undertake this function. Neither the third sector nor the private for-profit sector is currently entrusted with this responsibility. These relations can be summed up in Figure 1.1.

The purpose of this book is to focus on the third sector as a provider of public financed welfare services. It argues that the third sector can promote a better work environment for the staff and therefore better quality services. It also facilitates greater citizen participation in the provision of welfare services and this, in turn, results in a more financially sustainable welfare state.

The triple dilemma facing the universal welfare state in Sweden

The universal welfare state in Sweden is currently facing three major dilemmas that challenge its future and sustainability. In brief, it suffers from low-quality public welfare services, low citizen participation in political life and high costs of producing universal welfare services. This is the result of:

a the declining quality of public services due to the poor work environment in the public sector following major cutbacks in public financing during the 1990s;

b the growing democracy deficit, in spite of very high democracy scores and voter participation; and

c the permanent austerity of financing welfare services due in part to a rapidly ageing population and in part to the world’s highest taxes.

Sweden must therefore develop a strategy to move from the current situation to the opposite one of high-quality welfare service, greater citizen participation in the provision of welfare services, and lower costs for providing such services. In order to do so, Sweden must successfully resolve the three interrelated challenges of:

a improving the service quality by improving the work environment of the women providing welfare services;

b increasing possibilities for citizen participation in and control of the services they demand and pay for through...