1 Introduction

National parliamentary elections conducted under the first-past-the-post electoral system typically result in the election of majority parliaments and the formation of a single-party majority government. India, however, has become a very important and puzzling exception to this pattern during the past 17 years. Although India has used the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system, none of her general elections has produced a majority winner since 1989 and only one of them was followed by the formation of a majority-size government. In short, electoral and parliamentary majorities have become elusive properties of the world’s most populous democracy.

Parliamentary elections that fail to provide a decisive mandate to govern are particularly problematic in a majoritarian democracy like India, where the main political institutions, inherited from British colonial rule, are expressly designed to facilitate the formation of an effective political majority as opposed to the creation of a broadly based consensus and power sharing (Lijphart 1999). Moreover, governing a complex and divided society like India’s without the support of either a clear electoral mandate or a legislative majority also runs the risk of seriously weakening the bond between state and society and undermining the legitimate foundations of the country’s democratic establishment. Therefore, it is very important that we have an accurate understanding of the reasons why electoral and political majorities are increasingly more difficult to forge.

This book tries to offer an explanation for the puzzling absence of electoral and parliamentary majorities in India in the period 1989–2004. The Indian case is an important addition to the literature on the politics of multiparty government that has had a traditional bias toward the study of Western Europe (see, for example Laver and Schofield 1990; Laver and Shepsle 1996; Muller and Strom 1999, 2000). Moreover, the study will also offer a valuable comparable case for scholars examining the development of post-dominant party systems, such as Japan or Mexico, as well as to those who study the relationship between the FPTP electoral rule and the party system in other countries, such as Britain, Canada or the United States (Chhibber and Kollmann 2004, 1998). A number of recent works have addressed the transformation of the Indian party system with specific focus on the increase in the number of parties (Chhibber 1999; Chhibber and Kollman 1998, 2004; Sridharan and Varshnoy 2001; Yadav 1996), the strategies of electoral mobilization (Chandra 2004) and the specific contextual features of the elections in the new Indian party system (Roy and Wallace 1999; Wallace and Roy 2003). However, the study of coalition politics, including the formation and the durability of both electoral and executive coalitions as well the consequences that they have for other aspects of the political system, has not been systematically addressed. It is this gap in the literature that the present book seeks to fill.

The context

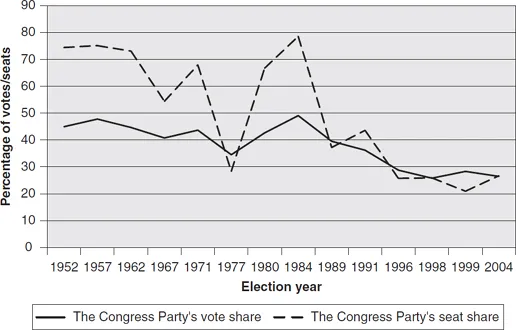

The national party system of India has undergone a profound transformation since the parliamentary elections of 1989. In stark contrast to the preceding decades, the pattern of party competition is no longer characterized by the dominance of the Indian National Congress Party which used to be able to command impressive parliamentary majorities and form stable and efficient governments after almost every national election that has been held since Independence. Today, the Congress is still a very important player in the party system; however, it no longer carries the prestigious status of being the natural party of government in the world’s most populous democracy. Figure 1.1 documents the performance of the Congress Party in India’s national elections.

The vacuum left behind by the decline of the once dominant Congress Party has not been effectively filled by any single political force on the national scene of party competition. The most ostensible indication of this is the fact that neither a single political party nor a coalition of parties has succeeded in winning a majority of parliamentary seats in five of the six elections held to date since 1989. The only exception to this pattern was the bare majority victory mustered by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), a pre-electoral coalition put together and led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party in the general parliamentary elections of 1999. However, the NDA lost the next election to the alliance led by the Congress Party and thus was not able to consolidate its position as a new dominant partisan force in the country. In fact, regular alternation in government has become yet another recurring characteristic of the new reality of India’s party system. Apart from the 1998 and 1999 elections, both of which brought to power the NDA, the electoral pendulum consistently swung between left and right with every election.

Figure 1.1 The performance of the Congress Party in Lok Sabha elections, 1952–2004

Note: Author’s calculations based on official electoral returns provided by the India Central Election Commission.

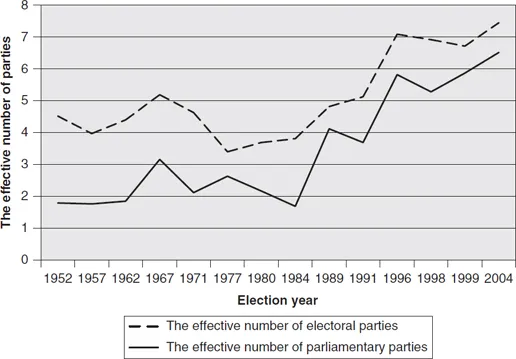

The decline of the Congress Party has been marked and followed by extreme degrees of fragmentation in both the electoral and the parliamentary arenas of party competition. Compared to the election of 1984, when only 33 parties entered the national electoral race, the number of parties in the 1989 elections has increased by more than threefold to 113 and has grown continually ever since. In the election of 2004, a total of 230 different political parties entered the race officially. This explosion in the sheer number of partisan contenders has been also reflected in the increase in the weighted ‘effective’ number of political parties, whichhas increased from 3.81 in 1984 to a staggering 7.59 in 2004.1 Such high levels of electoral fragmentation are normally witnessed in countries that use proportional representation election systems; however, fora country, like India, that uses the first-past-the-post voting rule, such high degrees of fragmentation are puzzling.

The fractionalization of the electoral party system has caused a similarly striking level of fragmentation in the legislative arena of party competition also, as Figure 1.2 attests. While the average number of parties entering the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the national parliament, between 1952 and 1984 was 18.6, this number has almost doubled for the period 1989 to 2004 to 31.6. The ‘effective’ number of parliamentary parties has seen a similar explosion from an average of 2.13 in the decades leading up to 1984 to an average of 5.2 in the six parliaments elected in the period between 1989 and 2004.

Figure 1.2 The fragmentation of the national party system, 1952–2004

Note: Author’s calculations.

As the party system is becoming increasingly more fractured, India’s political parties have started to contest national elections by building pre-electoral coalitions and alliances rather than compete solely on their own. Thus, national elections in India are no longer fought along individual party lines as such but rather among the three to four main blocs of parties united to contest the elections. The relevance and significance of these electoral alliances transcend beyond the electoral arena into the realm of the game of government formation as these electoral coalitions become the key players whose size, ideological position and policy compatibility with the other partisan blocs determine who will form the next government and how durable it is likely to be. The party alliances that define the current Indian electoral and parliamentary landscape are structured according to a clear pattern: each of them is led by a major national party, representing the ideological core of the alliance, and includes a host of regional parties acting as the local ‘ambassadors’ ofthe party alliance in the particular region ofthe country where their electoral stronghold is concentrated.

Today, there are three major party alliances that define the contours of the Indian party system. These are the National Democratic Alliance on the right, consisting of the Bharatiya Janata Party and its allies; the United Progressive Alliance in the centre, represented by the Congress Party and its allies; and the Left Front led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The exact composition of these electoral coalitions has changed over time as we shall see in Chapter 3. However, the main national parties that define the ideological profile of the three alliances, the BJP, the Congress and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) respectively have remained stable and consistent both in their ideological positions as well as their competitive attitudes towards one another. The most significant exception to this is the Janata Dal, a national party, that led a fourth bloc of parties (known at first as the National Front then as United Front), positioning itself left-of-the-centre between the Communist-led Left and the centrist Congress-led alliance. The Janata Dal had entirely disintegrated by the time of the 1999 elections and so had the United Front that it was leading. It is indicative of the importance of alliances that the overwhelming majority of parties seek to be affiliated with one of the major blocs. After the 2004 elections, there were 13 parties, most of them very small, accounting for 72 seats in the newly elected Lok Sabha that were not attached to any of the main alliances.2 Party alliances have introduced an important degree of rationalization and orderliness in what was emerging to become a complex and atomized party system.

The fragmentation of India’s party system has had an important impact on the politics of government formation and government durability in the national parliament. Since parliamentary elections no longer result in majority victories, India’s political parties have had to reach agreements to form multiparty coalition governments after all but one of the national elections held since 1989. The only exception to the pattern of coalition governing was provided by the Lok Sabha elected in 1991 in which the Congress Party managed to form a minority government by itself. Apart from this case, every national government in India has been formed by a coalition of multiple political parties. Another closely related consequence of the transformation of the Indian party system pertains to the durability of national governments. In contrast to the previous decades, the post-1989 period is characterized by severe degrees of cabinet instability. Out of the six Lok Sabhas that were elected during this period, only three (those elected in 1991, 1999 and 2004) lasted for their mandated five-year terms. In two parliaments (those elected in 1989 and 1996), multiple cabinets succeeded one another in office until the Lok Sabha would be eventually dissolved to be followed by a call for fresh elections, while the Lok Sabha elected in 1998 was dissolved prematurely on the advice of the head of the BJP-led minority coalition government.

Comparative implications of the Indian case

The number of parties

The emergence of elusive electoral and parliamentary majorities in the Indian party system has three comparative implications. First, the fragmentation of the national party system is a major puzzle for students of comparative party systems because it continues to reaffirm that India is an exception to Duverger’s famous dictum about the relationship between electoral and party systems (Duverger 1954). According to Duverger’s Law, the first-past-the-post electoral system, which India has used in a pure form since 1962, should foster a two-party system, while according to Duverger’s Hypothesis proportional representation (PR) formulae ought to encourage the formation and proliferation of multiple political parties, thereby creating a more fragmented multi-party system. The national party system of India, however, never complied with the prediction of Duverger’s Law. Whereas the Law predicts the eventual equilibration of a national two-party system in India, this has never come about. This prediction was first falsified by the long period of one-party dominance by the Congress Party, and it continues to be defied today as the national party system becomes gradually and increasingly more fragmented. In fact, in terms of its fragmentation, the format of the current Indian party system is what one would expect, according to Duverger’s Hypothesis, under a PR system. Recent scholarship in the electoral and party systems literature (Chhibber 1999; Chhibber and Kolmann 1998, 2004; Cox 1997; Gaines 1999; Grofman, Bowler and Blais 2009) have shown that the theoretically appropriate level where Duverger’s Law should be expected to constrain the number of parties is the electoral district rather than aggregate national party system. How well Duverger’s Law has worked at the level of districts in India remains debated. According to Chhibber and Kollmann (2004), the Law has worked very well over time to limit the number of parties, however Diwakar (2007) reports evidence to the contrary. Our focus in this book, however, is not on the individual districts but on party politics at the systemic level, both at the centre and in the states. Therefore, the puzzle that we want to investigate and find the solution to is why local contests do not aggregate into a national two-party system, as they do in other countries that use the first-past-the-post electoral system, such as Britain or the United States. It is an important theoretical puzzle that begs further inquiry.

The degree to which the Indian party system has fragmented is quite unique even in comparison with the multi-party democracies of Western Europe. Table 1.1 compares the party system of India with those of continental Western Europe in the post-war period on two indicators: the mean values of the effective and the actual number of parties in parliament. Considering the entire period, India does not stand out from the rest of the party systems in terms of its mean parliamentary fragmentation (3.45), in fact, it stands right in the middle of the distribution close to Sweden, Norway and Luxembourg. However, in terms of the mean actual number of parties in parliament, the Indian party system does stand out from the sample. With a mean of 24.2 for the entire period, the number of parties in Indian party system exceeds more than twice the mean number of parties in Italy, the country next in rank. Compared to Austria, the country with the fewest parties in parliament, the mean number of parliamentary parties in India is almost eight times greater.

The last two rows in Table 1.1 de-compose the Indian mean scores in two time periods: the majoritarian period (1952 to 1984) and the period of elusive majorities (1989 to 2004). These numbers reveal the dramatic differences that distinguish the party systems of these two eras. In its majoritarian period, India had a lower mean effective number of parliamentary parties than any other West European multiparty system. This is, in fact, what one might expect given that no other country in the sample uses the plurality electoral formula that Indian employs, although the mean actual number of parliamentary parties still remains considerably higher than in the rest of the countries. In the era of elusive majorities, however, the Indian party system becomes the second most fragmented in the sample with only Portugal having a more fractionalized legislature than India.

Table 1.1 The Indian party system compared with Western Europe

Scholars have tried to account for India’s non-conformity with Duverger’s Law for a long time. In an early statement, Riker actually reformulated Duverger’ s Law, stating that‘ [p]lurality election rules bring about and maintain two-party competition except in countries where (1) third parties nationally are one of two parties locally, and (2) one party among several is almost always the Condorcet winner in elections’ (1982: 761). In this, Riker drew on earlier work by Rae (1971: 95) who was the first to link Canada’s multiparty format to the presence of locally strong parties, which was facilitated and sustained by a federal state structure. Recently, several authors have made a very similar point with regard to India noting that the country’ s national multi-party system is the reflection of the aggregation of multiple bipolarities from the sub-national level to the national level of competition (Sridharan 2002, 1999; Sridharanand Varshney 2001; Yadav 1996). If so, then the root causes of multipartism in both Canada and India may be essentially the same! Yet, Riker did not go so far as to suggest that the presence of ’strong local minority parties’ could also explain party proliferation in India. Instead, he explained the Indian puzzle by the second condition of his reformulated Duverger’s Law: the Indian party system had a large centrally positioned party, the Indian National Congress, which included the median voter, and as such was a Condorcet winner, in most districts. As a result of its central positioning, Congress pre-empted its opponents’ ability to aggregate and merge into a national ideologically connected anti-Congress rival party in the national party system (Riker 1976, 1982: 271).

A second important line of explanation for the unusually large number of parties in India stresses the effect of changes in the distribution of power between the national and the sub-national governments (Chhibber and Kollman 2004, 1998). According to this view, the number of parties in the national party system varies positively with the degree of economic centralization: as the central government assumes greater economic authority political elites become more interested in forming large parties that can capture the national government. Conversely, economic centralization reduces the incentives for party aggregation. A third perspective posits the complex cleavage structure of the country to be responsible for its multiparty system (Chhibber and Petrocik 1989). This view is in accordance with the broader claim made by Taagepera and Shugart that when many ‘issue dimensions are significant in a given polity, the number of parties may remain high regardless of the pressures exerted by the mechanical and psychological effects of the electoral system’ (1989: ...