1 Origins

The overwhelming majority of the population of the Northwest Caucasus for centuries consisted of the Adyghe-Abkhaz ethnic group and, somewhat later, Iranian and Turkic peoples. Numerous invasions by nomads of diverse backgrounds and peaceful intermarriage with Georgian, Armenian, Greek, Slavic and other tribes not only brought new ethnic groups to the region but also created close familial and cultural ties between all groups. The history of one Northwest Caucasus people is to a great degree the history of all.

While much of the evidence is fragmentary and theories about the origins of the peoples of the Northwest Caucasus are far from definitive, many conclusions about the prehistory and early historical development of the region can be made. Likewise, despite numerous upheavals caused by invasions and conquests the emergence and development of the modern cultures of the Northwest Caucasus can be traced.

Circassians

The Adyghe-Abkhaz peoples are the most ancient residents of the West Caucasus. Sometime before 500 CE they split into four subgroups: the Abazas, Abkhazis, Circassians, and Ubykhs. The largest representative in the Northwest Caucasus is the Circassian (Adyghe) ethnic group. Currently, there are two distinct groups of Circassians. The Kabardians organized a feudal state which led to ethnic and linguistic consolidation by the sixteenth century CE. The western Circassians consist of the remnants of various tribes which were for the most part deported to Turkey in the 1860s, and who speak a variety of similar dialects distinct from Kabardian.1

A large body of archeological, cultural, and linguistic evidence points to an ancient culture throughout the North Caucasus dating back to the Paleolithic Era.2 This population probably served as the substrata from which all the indigenous peoples of the Caucasus emerged. Differentiations between Northwest, Northeast and South Caucasus peoples were the result of the influence of later arrivals who superimposed their cultural and linguistic features upon this original population. Further evidence indicates a stable indigenous civilization in the Northwest Caucasus for nearly 5,000 years. The general consensus of Russian anthropologists and archeologists is that these early inhabitants supplied a significant element of the Circassian, as well as Karachai-Balkar genetic pool.3 There is strong linguistic and archeological evidence that the immigrants who came to the Northwest were related to the Hatt people of north-central Anatolia, and who migrated eastward under pressure by the Hittites in the third millennium BCE.4

Figure 1.1 The modern North Caucasus region, including the Northwest Caucasus Republics of Adygeia, Karachaevo-Cherkessia, and Kabardino-Balkaria (courtesy of adygaunion.com).

The Greek colonies

In the eighth century BCE the peoples of the Northwest Caucasus unified into the so-called Kuban culture, which stretched from the Taman Peninsula to Sochi in the south, and along the left bank of the Kuban as far as western KarachaevoCherkessia around the end of the second millennium BCE. Greek historiographers classified the peoples of this civilization into numerous tribal affiliations.5 The origin and significance of many of the Greek appellations are problematic and sometimes contradictory, and often the tribes were only known from second- and third-hand reports.6 These early residents of the Northwest Caucasus were farmers of wheat, barley, and millet, and breeders of cattle, sheep, horses, and pigs. The tribes along the Azov coast engaged in fishing as well. There appears to have been a well-developed social order, including wealthy families and social stratification throughout society.7 One tribe, identified by the Greeks as the “Meots,” had a ruling class, militias, and a professional military force.8 After the arrival of the Greeks, the two parties traded extensively, although antagonistic relations and armed conflict ultimately ensued. Nevertheless, the Greeks adapted to the conditions in which they found themselves and began to engage in agriculture as well. By the fourth century BCE large volumes of grain were being shipped from the region to Greece and other locations in the Mediterranean.9 There is also evidence that the Greek colonies became centers for artisans from among the indigenous population.10

The other major indigenous tribe, the Sinds, achieved greater prosperity than the Meots. Their territory stretched from the Black Sea coast near modern Novorossiisk to deep into the Caucasus lowlands and perhaps the steppes of southern Russia. Like the Meots, they engaged in agriculture, animal husbandry, and fishing. The Sinds developed agriculture to a level equivalent to the Greeks of Asia Minor, employing plows extensively. By the fifth century BCE the Sinds had developed a government and class system and established several cities to facilitate trade. The Sind capital was Gorgippia, located on the site of the modern city Anapa. Archeological data indicates significant Hellenic influence; there is even evidence that the Greek chorus became incorporated into Sind culture. Sind aristocrats surrounded themselves with the finest Greek artifacts and were buried with them.11

Once the Greeks colonized the northern and eastern shores of the Black Sea in the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, cities arose in rapid succession, the most important of which was Thanagoria on the Crimean Peninsula. A fusion of Greek and local culture resulted in a unique form of Hellenic civilization which was considered semi-barbaric by the traditional centers of Greek civilization but achieved a relatively high level of cultural development and became active trading centers.12 These cities functioned as autonomous poleis until around 480 BCE, when they were united by the Archaeanactid Dynasty into the Bosporus State. Strategically situated, the Greeks were able to control trade throughout the entire eastern Black Sea. The value of this location would lead to countless wars that repeatedly devastated the Northwest Caucasus.

The Archaeanactids sought peaceful and cooperative relations with the Meots and Sinds, but in 438 they were supplanted by the Spartocids, who quickly sought territorial expansion. This led to internal disputes among the Sind aristocracy and culminated in a war at the end of the fifth century BCE. A bit of intrigue was involved. Based upon the writings of the Greek historian Polien, it appears that Satir, ruler of the Bosporus State at this time, assisted the deposed Sind ruler Gekatei in regaining his throne. Tirgatao, Gekatei’s wife, was considered problematic to the Bosporus and so Gekatei placed her under arrest. She quickly escaped and returned to her compatriots, the Iksomat tribe. The Iksomat, aided by numerous Meot tribes, carried out two campaigns against Gekatei. The war concluded when Satir’s son Gorgipp managed to negotiate a peaceful settlement that was much to the advantage of the allied Iksomat forces. Over the next century the Sinds and Meots became an integral part of the Bosporus State and began to play a significant role in its internal politics. In 309 BCE internal struggles brought an end to a unified state for 200 years, when a new Bosporus political entity was established and the Meots and Sinds were once again incorporated into the Greek polity. However, as their military successes against the Bosporus demonstrated, the Meots had already developed into a relatively unified entity capable of collective action.13

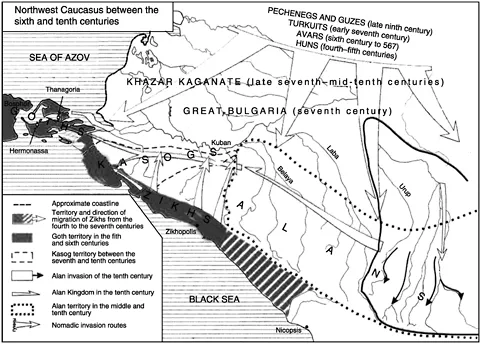

Figure 1.2 The Northwest Caucasus between the sixth and tenth centuries (courtesy of adygaunion.com).

Nomadic incursions

The unity provided by the Greeks was brought to an end by the incursion of the Sarmatians beginning in the third century BCE. These Iranian tribes occupied the steppes between the Don and Ural Rivers until the fourth century BCE, when they moved into the land north of the Kuban River. This new influx dramatically changed both the demographic and political picture.14 The unity of the Meots was destroyed, and those tribes north of the Kuban were ultimately assimilated linguistically into the Sarmatian population. Beyond the Kuban the opposite process took place. While the Sarmatians dominated the Meot lands, they were themselves assimilated and the language of the Meots, the predecessor of the modern Circassian dialects, survived. The two cultures influenced one another despite their linguistic differences, and the pattern of North Caucasus civilization was begun: a single way of life practiced by peoples speaking unrelated languages and viewing themselves as distinct ethnic groups despite their common roots. The Greeks’ role in the region was greatly diminished during this period; the Sarmatians disrupted their economic ties with the indigenous populations while their ties with Greece weakened and internal conflicts became frequent.15

The expansion of the Alans at the beginning of the Common Era forced the Meots living on the plains north of the Caucasus highlands to migrate beyond the Kuban River to the lands still under the control of the Meots, who were now united in a confederation known to outsiders as the Zikhs. The Alans gradually adopted the sedentary lifestyle of the North Caucasus peoples and the two cultures merged. The Alans did not assimilate the mass of Meots in the Zikh confederation due to the Zikhs’ extensive foreign trading relations, their established social order, and the widespread nature of their language. Nevertheless, the Alans certainly contributed to the ethnic roots of the modern Circassian people and impacted cultural traditions in Circassian society.16 When their power was broken by the Huns, who achieved their first victory in 371, the Alans dispersed and their kingdom collapsed, only to re-emerge after the Huns disappeared.

The origin of the term “Zikh” is unclear. Writing in the first century CE, Strabo refers to the “Zigei” as a people living beyond Gorgippia (near modern Novorossiisk) in a “harborless and mountainous” region, and who made their livelihood from piracy, even mounting raids on other colonies on the Black Sea.17 The Romans mention the Zikhs as early as the second century CE, and by the fourth century there were Zikh emissaries in Rome and Roman missionaries, merchants, and soldiers in the Zikh lands.18 Judging from classical documents, the Zikh confederation began in the environs of the modern city of Tuapse, and expanded during the period from the third to the fifth centuries to encompass the land that would eventually be home to the western Circassians, the northeastern shores of the Black Sea. During the period of nomadic invasion, particularly the devastating raids of the Huns, the Zikhs were shielded by their mountainous terrain. Lacking any convenient ports, the coast along the Zikh homeland was never colonized by the Greeks, and an expedition against them by allies of the Bosporus State in the first century BCE was aborted owing to the horrific weather (which would frustrate the Russians 1,900 years later). Besides the aforementioned piracy, the Zikhs engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry, and eventually developed vibrant industries in ceramics, metal tools, weaponry, bricks, and tile.19 Another group, the Kasog, is distinguished from the Zikh confederation in Byzantine chronicles. While the Zikhs inhabited the coastal regions, the Kasogs occupied the steppes north of the Caucasus range. This distinction disappeared by the tenth century, when the Arab scholar Masudi traveled to the North Caucasus and described a single confederation which he called the “Keshak.”20 By the thirteenth century the term “Cherkess” appears, from which the English term “Circassian” is derived.21

The downfall of the Alan kingdom was a tumultuous affair for all the peoples of the North Caucasus. Four years after the Alans’ first defeat at the hands of the Huns in 371 a Hun army estimated at 300,000 crossed the Volga, devastated the Sarmatians and Alans living north of the Kuban, and moved unopposed into the Northwest Caucasus. Thanagoria, Hermonassa, and other cities on the Kerch Peninsula and the Gulf of Taman were destroyed and their populations annihilated. The Huns then moved into the Sind lands and totally destroyed their urban centers. With Alan power broken, Turkic nomads were able to penetrate the North Caucasus unopposed throughout the fifth and sixth centuries. Greek chronicles mention no fewer than 11 different waves of invaders during this period, a list that is most likely incomplete. The first major political unit to arise from these invasions was Greater Bulgaria, which at its height stretched from the Taman Peninsula to the steppes along the Don River. Little is known about this state except that after the incursion of the Turkish Kaganate, a nomadic Central Asian confederation, onto the Taman Peninsula in 576 their power declined. By the ninth century many Bulgars moved into the lowlands around the Kuban River and the central Caucasus range, where excavations have uncovered traces of their presence in the eastern regions of Karachaevo-Cherkessia.22

The Byzantines

Circassian records report the first appearance of Greek Christian missionaries at the end of the third century, but under Emperor Justinian (525–65) missionaries traveled to the North Caucasus in large numbers in conjunction with Byzantine efforts to gain control of the resources of the North Caucasus.23 In 533 Greek forces landed on the Kerch Peninsula and declared the area to be under suzerainty of Constantinople. At this time Justinian was also forging alliances with confederations to the north of the Azov Sea, primarily remnants of the Huns. By the second half of the sixth century, Constantinople was using its new power in the Northwest Caucasus to confront Sasanid Iran, which held a large portion of the Northeast. At that time the Great Silk Route went through Iran; it was the Byzantines’ goal to shift the Route north of the Caucasus Mountains to their economic advantage.

In 569 Constantinople and the Turkish Kaganate joined forces against Iran and successfully shifted the Silk Route.24 The transfer of the Route into Byzantine hands greatly enhanced the economic potential of the region and helped the indigenous peoples regain much of the stability lost during the repeated nomadic incursio...