1 Introduction

Sensing cities

Jane: I like looking at the shapes and how they have changed.

Monica: How have they changed?

Jane: Well, we’d first got dirty scrap-yards and now we’ve got clean, plain lined, modern buildings.

(Jane, tourist guide in Castlefield)

Monica: And what do you think about the new Plaça dels Angels?

Rafael: A disaster, a disaster as a square, a disaster from an urban planning point of view, and a disaster because of the ‘ambience’ you get there… It is a centre for reunion for all those people: skateboarders, people who take their dogs there to shit, people who just sit around. Not so much in winter but in the summer you get a proliferation of people from the Third World: Filipinos, Pakistanis, Moroccans and they eat there and drink there… and throw all the rubbish around.

(Rafael, shop-owner in El Raval)

Walk down any street in any city. What can you hear, feel, smell, taste and see? Your body brushes against other bodies; a cacophony of voices echoes in your ears; your nostrils are teased by smells emanating from shops; your eyes captivated by the bright displays shining through smooth glass windows set against the rough stone of red bricks. Or maybe your body senses the emptiness of a street, perceiving the lack of fellow pedestrians; the overwhelming traffic noise; the taste of smog; the stench of the gutter; and the endless rows of identical housing. Wherever you are in the city, as soon as you move into a street you are involved in an intense sensuous1 encounter. The senses play a crucial role in mediating and structuring urban experience.

In this book I focus on this important yet largely neglected dimension of urban life: namely the significance of the senses in the (re)configuration of contemporary public space and life. The senses mediate our contact with the world as one engages in public life through the body: ‘the city exists in my embodied experience’ (Pallasmaa 2005: 40). The architecture, streets, shops and social life we encounter, people’s behaviour and activities, all amalgamate through our embodied perception to create a ‘sense of place’. The mix of material and social features arouses sensuality and their combination produce the ever fluctuating nature of public life: ‘the relationship of public space to public life is dynamic and reciprocal’ (Carr et al. 1992: 343).

Public places provide the tangible and physical realm for a shared sense of being with other humans. Even in late modernity, with technological advances such as the internet shaping new public spheres, social intercourse in public spaces has not diminished. Indeed, broader social and economic restructurings since the 1970s have meant that the city is the focal point of a new post-industrial economy which attracts ever more people to live in, work in or consume its sites. Significant here is that cities across Western Europe and further afield have been involved during the last two decades in an intensified period of urban renewal that has paid particular attention to the redevelopment and redesign of public space (Harvey 1990, 2000; Hall and Hubbard 1998; Castells 2002; Madanipour 2003, 2006). This remodelling of urban space entails an intense reassembling of the physical landscape that is evaluated in conflicting ways as the above quotations illustrate. My concern in this book is not with charting the reasons and politics behind these processes per se. My concern is rather to understand how regeneration processes transform the sensory qualities of places and whether this sensuous reorganization excludes or includes particular cultural expressions and practices in the public life of these spaces.

To examine the role of the senses in framing public space and life I focus on two neighbourhoods that have witnessed profound transformations in their physical set-up in a relatively short span of time: Castlefield in Manchester and El Raval in Barcelona. Let me briefly elaborate on my reasons for doing so. During the mid-1990s I was travelling regularly between Barcelona, my home town, and Manchester. Spending long periods of time in these cities made me realize that the ‘character’ of these cities was rapidly transforming as similar changes were taking place. Two areas particularly caught my attention: Castlefield, a place I observed periodically from a railway bridge on my way to Manchester airport, as it slowly metamorphosed from a grey, industrial space into a whitewashed and landscaped leisure area, criss-crossed by canals; then, after a two-hour flight, Barcelona, a city that has reinvented itself dramatically since the death of the dictator Franco in 1975. There, I would spend afternoons walking through the narrow, run-down streets of the lively Raval, situated next to the wellknown boulevard of Las Ramblas. Once the infamous red light district of Barcelona, this neighbourhood, like Castlefield, was being ‘cleaned up’.

Although the urban landscape and cultures of both cities were very different, similar patterns started to emerge in these neighbourhoods. Both places were reorganizing their urban environment with a special emphasis on redesigning their public spaces. Both areas used the construction of major flagship cultural projects such as the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona in El Raval, and the Museum of Science and Industry in Castlefield, to inscribe new values into the landscape and promote a new neighbourhood image. This meant that streets were widened, new street-furniture was introduced, buildings were sand-blasted, and so on. Indeed, these new public places felt and looked remarkably similar.

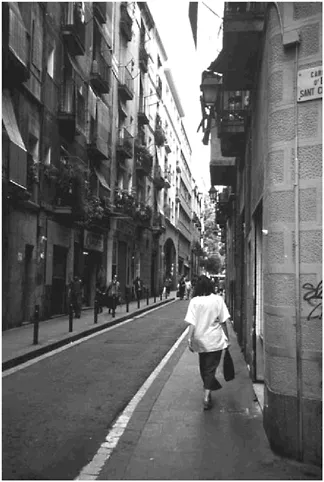

However, the existing physical set-up of each place and their sociocultural setting could not have been more different. El Raval contains a varied building stock ranging from a Romanesque church to fifteenth-century buildings and predominantly nineteenth-century housing. It is an area characterized by confined spaces, a network of small squares, narrow streets, courtyards and passageways. Historically a neighbourhood of crowded living conditions, it was still densely populated at the time of its regeneration. Many of its residents have lived here for two or three generations, a feature reflected in the large number of family-run corner stores and workshops on its streets and its intense vernacular street-life. By contrast, in Castlefield the existing building structures were mainly those of a nineteenth-century industrial landscape, with large open spaces interwoven with canals and hardly any resident population to take into account at the start of the regeneration. Despite contrasting social environments—a southern European neighbourhood with an already rich public life, and a northern European one, lacking public life—a similar form of global spatial practice was enforced to change the existing public space: cultural regeneration (Bianchini and Parkinson 1993).

Figure 1.1 A street in El Raval. (Photograph by author.)

Figure 1.2 A street in Castlefield. (Photograph by author.)

Urban regeneration schemes are long-term projects dependent on cycles of investment that make it difficult to assess when a place is ‘finished’. Both Castlefield and El Raval are constantly evolving. Indeed, Castlefield is now populated by a largely homogeneous, predominantly white, middle-class population, whereas El Raval has been transformed into ‘Barcelona’s cul tural paella pan’ (Time Out 2001: 76), and is one of the city’s most racially mixed neighbourhoods. I have therefore restricted the focus of my empirical study to the years between 1997 and 2002 when the key spatial restructuring took place and the socio-spatial and sensuous changes were most acute and perceptible. In exploring the links between spatial transformations and sensuous experience the book provides a critical account of the impact of regeneration strategies on the experiential landscape of cities. By way of introduction I elaborate briefly on how the three key themes that run through my book—globalization and urban change; the senses and urban experience; and public space and life—are connected, and set out why a focus on the senses is necessary to examine contemporary processes of urban redevelopment.

Urban redevelopment, the senses and public life

In her article assessing the development of urban sociology at the start of the new millennium the sociologist Saskia Sassen states that after a decline of interest in the city during the second half of the twentieth century, ‘the city is once again emerging as a strategic site for understanding major new trends that are reconfiguring the social order’ (2000: 143). The key new trend that Sassen refers to is globalization. Her argument is that with the decreasing role of the nation state, cities are becoming the main players in the world economy and are using their physical space to attract business, tourists and global investment. In this global network, places become interrelated structurally through a range of features such as international economic and political networks; an increasingly mobile ‘public’ constituted equally by tourists, commuters or migrant populations; or through the exchange of ideas and discourses. This intensified cross-reference between places fostered by global processes has meant that the notion of ‘place’ as a fixed and bounded entity has undergone a number of critical re-evaluations (Keith and Pile 1993; Eade 1997; Massey 1995b, 2005). Place is increasingly understood ‘as a meeting place, the location of the intersections of particular bundles of activity spaces, of connections and interrelations, of influences and movements’ (Massey 1995b: 59). Such a ‘dialogic’ notion of place acknowledges the inherent complexity of place materially, socially, politically and economically, and views globalization as far from a unified, singular process, but rather as multiple and unstable (see King 2004 for a overview of the use of this concept). In other words, globalization processes are not uniform but place-specific, as they get reworked in and through particular local contexts. Cities are precisely the places ‘where a multiplicity of globalization processes assume concrete, localized forms… Recovering place means recovering the multiplicity of presences in this landscape’ (Sassen 2000: 147).

Urban regeneration schemes present ideal sites to analyse the ‘multiplicity of presences’ and to examine how these diverse and often contradicting processes of globalization are transformed and appropriated in different locations by diverse audiences. Or, to put it more poignantly, to help us realize that ‘[w]hat is seen as globalization looks very different from different points of view’ (King 2004: 42). Let me briefly explain this point by referring to Baltimore’s harbour redevelopment which can be regarded as the template for many regeneration projects both in the United States and Europe. The transformation in the early 1980s of a once industrial area filled with disused wharves, warehouses and railways into a refurbished retail and entertainment festival market would become a much cloned model all over the globe, and regarded as financially beneficial to the image and economy of the city. One of the principal aesthetic features of regeneration projects is the physical transformation of the landscape through the integration of heritage, landscaping and leisure in the design of place, both in order improve the ‘quality of life’ in the area and to attract visitors. As Harvey explains, functionalist architecture was replaced in Baltimore by ‘an architecture of spectacle, with its sense of surface glitter and transitory participatory pleasure, of display and ephemerality, of jouissance, [that] became essential to [its] success’ (1990: 91). Significantly a key element in the successful redevelopment of Baltimore was the alteration of the sensory properties of its material landscape.

For some the regeneration of Baltimore has been successful because the remodelled space has attracted new business and visitors and provided an attractive image of the city that has fostered investment and civic pride. Critics, however, point out that such regenerated landscapes are ‘pockets of revitalization surrounded by areas of extreme poverty’ (Levine quoted in Hannigan 1998: 53). As Levine (1987), and more recently Harvey (2000), argue in their assessment of Baltimore’s redevelopment, the local population benefit little from these schemes, and are often vehemently opposed to them. The reasons range from more structural arguments, such as the worsening of the social and economic conditions of the less well-off due to spending on prestige areas taking precedence over welfare services, to a painfully personal perceived erasure of local culture reflected in the demolition of familiar sites and buildings. Similar criticisms have been voiced against the regeneration of Birmingham (Hubbard 1996), the London docks (Foster 1999), Manchester (Quilley 2000) and Barcelona (Heeren 2002; Degen and Garcia 2008). Hence, as a global process, regeneration is perceived very differently by a range of social groups affected and involved in these processes. Yet little attention has been given to local variations or the lived culture of entrepreneurial cities (Hall and Hubbard 1998), and few studies have analysed how these new landscapes are embedded in the everyday life of a range of social groups.

To date, most studies of the cultural transformation of urban space have analysed three main themes: the privatization and commodification of public space (Sorkin 1992a; Hannigan 1998); the rising influence of culture in determining the cities’ economy (Zukin 1995; Scott 2000); and gentrification (Ley 1996; Smith 1996; Atkinson and Bridge 2005). What these studies have in common is that they highlight how culture has become a key factor in the development of urban planning considerations, in the negotiations around the use of public space, and in the shaping of public life. Culture is the new battleground in cities which determines who is included or excluded in the public life of urban environments (Zukin 1995; 1998a). This book takes these positions as a starting point to expand the study of urban change in a number of new directions.

First, most accounts of urban change tend to focus narrowly on the American experience of major global cities and examine mainly large-scale urban developments2 (Soja 2000). However, with the expansion of neoliberal urban politics across the globe these features are also to be found in the regeneration strategies of many neighbourhoods, both in Europe and elsewhere (Peck and Tickel 2002). The novelty of new global urban conditions such as regenerated spaces provides a rare opportunity for comparative cross-cultural research on the discourses that inform the planning of these spaces, the practices of their users3 and the social significance that regenerated public space has in the entrepreneurial city. There is a general lack of comparative analysis on the restructuring of urban space from a cultural perspective that interrogates the ‘localism’ of place and considers how different local circumstances and a different set of local attitudes might reframe the outcomes of global cultural processes. In what ways does the vernacular culture play itself out within similar regeneration processes? What do these transformations mean for the type of public life that is created in regenerated urban environments?

Second, the experience of cultural and physical space restructuring tends to be summed up mainly from a visual perspective, often under the concept of the ‘aestheticization of everyday life’ (Featherstone 1991), or ‘spectacu-larization’ (Boyer 1988, 1992, 1995; Hannigan 1998). These environments create a distinct aesthetic in their spatial arrangements, their promotional campaigns and their sensuous perception, creating new experiential landscapes. Yet the changing urban space is not experienced via the visual sense alone but through the whole sensory body. A central issue in this book is therefore to understand how the sensuous perception of social space contributes to or undermines the social and ideological cohesion of the city. In other words, how does the sensuous organization of public space enhance or exclude the participation of particular groups in public life?

Third, studies on gentrification have tended to demonstrate how neighbourhoods transform socially through the influx of the middle class and the gradual expulsion of working-class or ethnic minorities. I broaden this analysis by considering further factors of neighbourhood change, particularly those that transform the individual’s attachment to place. A sensuous-spatial analysis of neighbourhood change provides a framework to analyse the relationship between physical, cultural and social transformations of public place. While literature on the spatial addresses the influence of capitalism in defining power structures in spaces (Harvey 1990; Castells 1996; Zukin 1991) and the imposition of landscapes and aesthetic taste (Zukin 1988; Featherstone 1991), little research has been done into how this affects daily social interactions: in other words, quotidian public life in these landscapes. My study aims to get closer to the lived and embodied experience of the agents involved in and affected by urban restructuring. What are the underlying cultural codes that guide the reorganization of certain neighbourhoods? How do different groups negotiate these? What is the nature and articulation of urban change within lived embodied experiences?

In order to link transformations of space with an analysis of sensuous experience this study follows the tradition of thought initiated by Lefebvre (1991), who began to look beyond space as a ‘container’ for social action and instead started to interpret space as a product and producer of multiple forms of spatial practice: ‘Space is permeated with social relations; it is not only supported by social relations but it is also producing and produced by social relations’ (Lefebvre 1991: 286). Space is thus always political, meaning that social power relations are expressed in and through space. A focus on the senses offers a way of analysing the relationship between built form and social relations, as senses provide the framing texture for the material and social bond in public spaces. Paying attention to how the senses frame our experience of cities invites us to capture a largely ignored aspect of city life that is as significant as their physical structure, namely their ‘character’ or ‘mood’. Steve Pile makes a strong case for analysing more than the physical form of the city and for focusing on the less tangible features that are equally important in defining the essence of the city: ‘what is real about cities, then, is also their intangible qualities: their atmosphere, their personalities, perhaps’ (2005: 2).

In the first part of the book I therefore develop a theoretical framework around the concept of ‘socially embedded aesthetics’ that allows me to analyse how social relations in public spaces are constituted by, exercised through and embedded in the sensuous geography of place. I contribute to a growing amount of research on the senses and society. While there has been an increasing interest in the senses in recent years (Urry 1999, 2000; Howes 2005a; Bull et al. 2006), few studies have focused their attention on the ideological importance of the senses in the rest...