This is a test

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Saudi Arabia: An Environmental Overview

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A comprehensive overview of Saudi Arabia's environment, this volume is a unique and authoritative text on the geological and environmental aspects of Saudi Arabia, a country about which little is known by the outside world. Saudi Arabia is a fascinating country with a long tradition of environmental awareness and sensitivity, pitted again

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Saudi Arabia: An Environmental Overview by Peter Vincent in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geology & Earth Sciences. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

An environment discovered

Contents

| 1.1 Introduction 1 | ||||

| 1.2 Early European explorers 2 | ||||

| 1.3 The nineteenth century 2 | ||||

| 1.4 Twentieth century explorers 9 | ||||

1.1 INTRODUCTION

By way of introduction to a book dealing with the environment of Saudi Arabia I thought it of interest for the reader to learn about some of the more important, and mostly European, travellers and explorers who were drawn by the mysteries of the Orient, and specifically to the region now known as Saudi Arabia. Several of these desert adventurers made important environmental observations and their tales of travel in the desert encouraged others in their footsteps. Indeed, their exploits seem to have caught the imagination of modern-day adventurers who wonder, no doubt, how anyone could possibly manage without a 4 × 4 truck (Barger, 2000). But manage they did, and even though the golden age of exploration was soon over, and oil men in their planes had surveyed the whole country for black gold, much still remains to be discovered about the Kingdom’s environment and adventures are still to be had. Of course, the view of the environment presented here is decidedly Western and Orientalist and the commodification of the environment has become a pervasive theme of the Kingdom’s development trajectory. How this harsh desert environment is perceived by the declining numbers of badu is, as yet, an unresearched question – the other side of a fascinating coin. The term “bedouin,” is actually an Anglicisation of badawi, or badu in the plural, and is used to distinguish the nomadic Arab of the desert from those in villages and oases.

As the Kingdom progressively becomes the focus of the modern tourist gaze one can only marvel at the exploits of these early explorers, armed with rudimentary maps, often with no knowledge of local customs, and as Christians in a Muslim world. Mostly they were tolerated and some, such as Lady Anne Blunt almost revered, and now part of folk memory. Indeed, the Blunts’ crossing of the great northern sand desert of the Kingdom, An Nafud, and their stay in Jubbah is now part of the tourism literature for the Ha’il region.

1.2 EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS

For more than a thousand years, since the time of the Prophet Muhammad, Arabia was hardly known to Europeans. The difficulties of desert travel, and Arab caution towards non-Muslims, deterred exploration of Arabia by Europeans until the eighteenth century, and for nearly two hundred years the writings of these explorers remained the only sources of environmental information available to the outside world.

Prior to this period one or two adventurers had made their way to Makkah but seemed not to have been in interested in collecting scientific information. One of the first Europeans to visit the holy city was the swashbuckling Italian Ludovico de Varthema who joined a troop of Ottoman soldiers escorting a pilgrimage from Damascus in 1503. Instead of returning to Damascus, Varthema smuggled on board a boat and set sail for Aden. There his luck failed him and within a day of his arrival he was put in chains. His escape was arranged by the Sultana and he left Aden having spent about ten months in Arabia.

The first Englishman to visit Makkah was Joseph Pitts who was born in Exeter in about 1663. His life seems to have been full of adventure having been captured by an Algerine pirate during a sea voyage back from Newfoundland and then sold into slavery and bought by Ibrahim, a wealthy Turk. After a good deal of torture – mainly by being beaten on the feet with a stick, Pitts was persuaded to become Muslim. Pitts was sold for a third time to a kinder owner who took him to Jiddah, Makkah and Madinah on pilgrimage. Pitts was finally given his freedom on return to Algiers, and enlisted first in the Turkish army, and then the Turkish navy. He finally managed to get back to England in 1693 (Bidwell, 1976). Pitts wrote one of the first detailed accounts of the annual pilgrimage to Makkah, the hajj, and also published a plan of the city’s great mosque (Radford, 1920).

Another half century passed by before the first team of scientists visited the region when, in October 1762, a small expedition of six, relatively young men funded by King Frederick V of Denmark, arrived in Jiddah on board a pilgrim ship from Egypt. This ill-fated expedition was led by Carsten Niebuhr, a German surveyor, and also included the botanist Pehr Forsskål, a Swede by birth and a pupil of the great taxonomist, Linnaeus. Niebuhr made a map of the city and also recorded the temperature at hourly intervals for some days. As the expedition members were not permitted to go to Makkah they decided to sail south along the coast to Yemen. Niebuhr and his friends were treated to wonderful hospitality saddened by the fact that several of the expedition members died of a mysterious disease – possibly malaria. Niebuhr returned to Copenhagen in 1788 with a wealth of cultural and scientific information. Although his expedition travelled little beyond the environs of Jiddah he should be regarded a truly great pioneering explorer and the first western scientist to visit the Kingdom.

1.3 THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Arabia was still poorly known to the outside world and for the most part it was still a land of myth and legend. Still less was known about the physical environment. European interests seem to have been stimulated by Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Egypt in 1798. Along with his army of 30,000 soldiers there were nearly 1,000 civilians – mainly administrators, but also botanists, zoologists, artists, poets, surveyors and economists whose purpose was to document and describe all they came across. On their return home they had collected enough information to produce the twenty-three volume Descriptions de L’Egypte, which became the authoritative text on Egyptology for generations. All sorts of pharonic and Islamic treasures were plundered and sent back to Paris where they intrigued and fascinated all who saw them. As Victor Hugo noted in his preface to his volume of poems entitled Les Orientales (1829), “In the age of Louis XIV everyone was a Hellenist. Now they are all Orientalists.”

European exploration of the Middle East in the nineteenth century seems to have been almost, but not entirely, a British affair as, indeed, it was in East Africa and the search for the Nile’s source (Simmons, 1987). Doubtless Horatio Nelson’s victory over Napoleon in the Battle of the Nile on August 1798, was a turning point in the history of the region. One exception to the British dominance was that of the professional Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784–1817) who travelled in the region and converted to Islam. As Ibrahim ibn Abd-Allah he went on a pilgrimage to Makkah in 1814 convincing his challengers by his outstanding knowledge of the Qur’an and its wonderful poetic language. He mapped the city and also visited Madinah for several months. Burckhardt achieved much in his short life, including the discovery of Petra in Jordan. He died of dysentery in Cairo at the early age of 33. At about the same time the Spanish traveller, known as Ali Bey (1766–1818), also posing as a Muslim, set out from Cádiz in 1803, and travelled through North Africa, Syria, and Arabia. On reaching Makkah he fixed the town’s position astronomically. His exploits are recorded in Voyage d’ Ali Bey en Asie et en Afrique (1814).

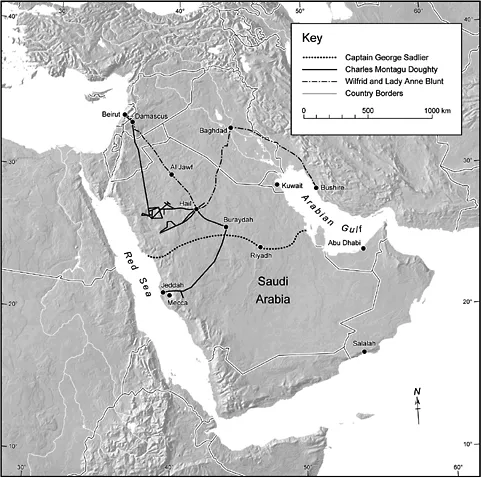

While most early travellers in Arabia seemed genuinely to like the people and the landscapes Captain George Forster Sadlier of the 47th (the Lancashire) Regiment of Foot loathed both. In 1819 the British authorities in India were concerned that marauding pirates were a threat to British trade in the Gulf. Sadlier was sent to negotiate help from Ibrahim Pasha who had captured the Wahhabis’ eastern capital of Dariya a year earlier after a siege of three months. In an attempt to meet up with the Pasha, Sadlier travelled from Qatif to Hufuf and then across the Nadj and onwards to the outskirts of Madinah and finally to Yanbu and Jiddah (Figure 1.1).

Sadlier had become the first European to cross Arabia and it would be another century before this intrepid journey was repeated. Sadlier scrupulously recorded the details of his journey in his diary and although of interest to contemporary geographers the crossing seemed to have interested him very little (Sadleir, 1977 – see note in bibliography regarding this misspelling).

In spite of Sadlier’s journey across the Nadj there remained some confusion as to where this region was precisely. As I shall note, several later explorers described their journey to the Nadj when in fact they were often to the north of it. One of the first Europeans to visit the northern Nadj was the Finn, Georg August Wallin who, in 1848 disguised as a learned Muslim Sheikh called Hajji Abdul-Moula, travelled from Jiddah to Ha’il and then on to the Euphrates. A hajji is someone who has undertaken the hajj (Arabic: pilgrimage) – one of the five Pillars of Islam. Unlike Sadlier, Wallin was interested in the geography and sociology of the region. A description of his journey was read in London to the Royal Geographical Society in 1852, and a rather

Figure 1.1 The Arabian journeys of Captain George Sadlier, Charles Montagu Doughty and Sir Wilfred and Lady Anne Blunt.

meagre account published two years later in the Society’s journal. A year earlier Wallin was awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s Founder’s Medal, “for his interesting and important travels in Arabia.”

In 1853, the British adventurer and polymath, Sir Richard Burton (1821–90) arrived in Arabia and, disguising himself as a Pathan – an Afghanistani Muslim, went to Cairo, Suez, Madinah, and then on to Makkah. Though not the first non-Muslim to visit and describe Makkah, Burton’s was the most sophisticated and the most accurate. His book Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Mecca (1855–56) is not only a great adventure narrative but also a classic commentary on Muslim life and manners, especially on the hajj. Burton had a...

Table of contents

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 An environment discovered

- Chapter 2 The Kingdom

- Chapter 3 Geological framework

- Chapter 4 Climate and environmental change

- Chapter 5 Hydrogeology and hydrology

- Chapter 6 Geomorphology

- Chapter 7 Biogeography

- Chapter 8 Soils and soil erosion

- Chapter 9 Environmental impacts and hazards

- Chapter 10 Environmental protection, regulation and policy

- References

- Index