![]()

Part I

Evolution

![]()

1 Intelligent design is untestable

What about natural selection?

Elliott Sober1

The argument from design is best understood as a likelihood inference. Its Achilles heel is our lack of knowledge concerning the aims and abilities that the putative designer would have; in consequence, it is impossible to determine whether the observations are more probable under the design hypothesis than they are under the hypothesis of chance. Hypotheses about the role played by natural selection in the history of life also can be evaluated within a likelihood framework, and here too there are auxiliary assumptions that need to be in place if the likelihoods of selection and chance are to be compared. I describe some problems that arise in connection with the project of obtaining independent evidence concerning those auxiliary assumptions.

1 What else could it be?

Defenders of the design argument sometimes ask “What else could it be?” when they observe a complex adaptive feature. The question is rhetorical; the point of asking it is to assert that intelligent design is the only mechanism that could possibly bring about the adaptations we observe. Contemporary evolutionists sometimes ask the same question, but with a different rhetorical point. Whereas intelligent design seems to some to be the only game in town, natural selection seems to others to be the only possible scientific explanation of adaptive complexity.

I propose to argue that intelligent design theorists and evolutionists are both wrong when they argue in this way. Whenever a hypothesis confers a probability on the observations without deductively entailing them, evaluating how well supported the hypothesis is requires that one consider alternatives. Testing the hypothesis requires testing it against competitors. Developing this point leads to a recognition of the crucial mistake that undermines the design argument. The question then arises as to whether evolutionary hypotheses about the process of natural selection fall prey to the same error. Although I’ll begin by emphasizing the parallelism between intelligent design and natural selection, I emphatically do not think that they are on a par. The relevant point of difference is that intelligent design, as a claim about the adaptive features of organisms, is, at least as it has been developed so far, an untestable hypothesis. Hypotheses describing the role of natural selection, on the other hand, can be tested. But how they are to be tested is an interesting question, as we shall see.

2 Likelihood and intelligent design

As mentioned, “What else could it be?” is a rhetorical question, whose point is to assert that some favored mechanism is the only one that could possibly produce what we observe. This line of reasoning has a familiar deductive pattern, namely modus tollens:

If H were false, O could not be true.

O is true.

(MT) _________ ____________ _________

∴ H is true.

Despite the allure of this line of reasoning, many defenders of the design argument have recognized that it is misguided. One of my favorite versions of the argument is due to John Arbuthnot (1710), who was clear about this point. Arbuthnot tabulated birth records in London over 82 years and noticed that in each year, slightly more sons than daughters were born. Realizing that boys die in greater numbers than girls, he saw that the slight bias in the sex ratio at birth gradually subsides until there are equal numbers of males and females at the age of marriage. Arbuthnot took this to be evidence of intelligent design; God, in his benevolence, wanted each man to have a wife and each woman to have a husband. To draw this conclusion, Arbuthnot considered what he took to be the relevant competing hypothesis – that the sex ratio at birth is determined by a chance process. Arbuthnot had something very specific in mind when he spoke of chance; he meant that each birth has a probability of ½ of being a boy and a probability of ½ of being a girl. Under the chance hypothesis, a preponderance of boys in a given year has the same probability as a preponderance of girls; there is, in addition, a third possibility that has a very small probability (e) – namely, that there should be exactly as many boys as girls in a given year:

Pr(more boys than girls are born in a given year | Chance) =

Pr(more girls than boys are born in a given year | Chance) >

Pr(equal numbers of boys and girls are born in a given year | Chance) = e

Thus, the probability that more boys than girls will be born in a given year, according to the Chance hypothesis, is a little less than ½. The Chance hypothesis therefore entails that the probability of there being more boys than girls in each of the 82 years is less than (½)82 (Stigler 1986: 225–226).

Arbuthnot did not use modus tollens to defend intelligent design; rather, he constructed a likelihood inference:

Pr(Data | Intelligent Design) is very high.

Pr(Data | Chance) < (½)82

(L) _________ ________ _______

The Data strongly favor Intelligent Design over Chance.

Arbuthnot used a principle that later came to be called “The Law of Likelihood” (Hacking 1965; Edwards 1972; Royall 1997): the data lend more support to the hypothesis that confers on them the greater probability. Here and in what follows, I use the terms “likelihood” and “likely” in the technical sense introduced by R.A. Fisher (1925). The likelihood of a hypothesis is not the probability it has in the light of the evidence; rather, it is the probability that the evidence has, given the hypothesis. Don’t confuse Pr(Data | H) with Pr(H | Data); the former is H’s likelihood, while the latter is H’s posterior probability. Understood in this way, Arbuthnot’s argument does not purport to show that the sex ratio data he assembled was probably due to intelligent design. To obtain that result, he’d need further assumptions concerning the prior probabilities of the two hypotheses.2 I omit these in my reconstruction of the design argument because I don’t see how they can be understood as objective quantities.

The likelihood version of the design argument is modest. As just noted, it declines to draw conclusions about the probabilities of hypotheses. But it is modest in a second respect – it does not claim to evaluate all possible hypotheses. Arbuthnot considered Design and Chance, but could not have addressed the question of how Darwinian theory might explain the sex ratio. This puzzled Darwin (1872) and was successfully analyzed by R.A. Fisher (1930) and then by W.D. Hamilton (1967). Thus, even if Arbuthnot is right that Design “beats” Chance, it remains open that some third hypothesis might trump Design. There is no way to survey all possible explanations; we can do no more than consider the hypotheses that are available. The idea that there is a form of argument that sweeps all possible explanations from the field, save one, is an illusion.3

I conclude that the first premise in the modus tollens version of the design argument is false. It is false that Intelligent Design is the only process that could possibly produce the adaptations we observe. Long before Darwin, Chance was on the table as a possible candidate, and after 1859 the hypothesis of evolution by natural selection provided a third possibility. In saying this, I am not commenting on which of these three explanations is best. I am merely making a logical point. What we observe is possible according to all three hypotheses. We can’t use modus tollens in this instance. Rather, we need to employ a comparative principle; the Law of Likelihood seems eminently suited to that task.

3 What’s wrong with the design argument?

To explain what is wrong with the design argument as an explanation of the complex adaptive features that we observe in organisms, it is useful to consider an application of this style of reasoning that works just fine. Here I have in mind William Paley’s (1802) famous example of the watch found on the heath. Construed as a likelihood inference, Paley’s argument aims to establish two claims – that the watch’s characteristics would be highly probable if the watch were built by an intelligent designer and that the characteristics would be very improbable if the watch were the product of chance. The latter claim I concede. But why are we so sure that the watch would probably have the features we observe if it were built by an intelligent designer?

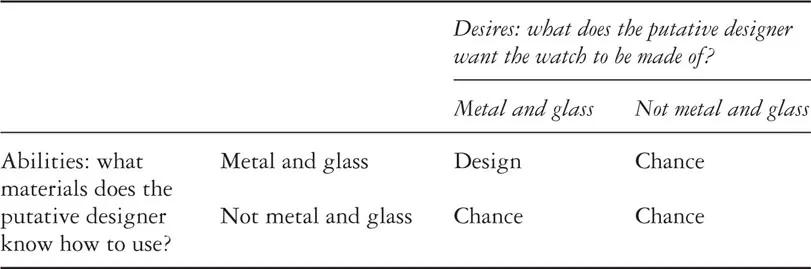

To clarify this question, let’s examine Table 1.1, which illustrates a set of possibilities concerning the abilities and desires that the putative designer of the watch might have had. The cell entries represent which hypothesis – intelligent design or chance – confers the higher probability on the watch’s being made of metal and glass.4 Which hypothesis wins this likelihood competition depends on which row and column is correct.5 The observation that the watch is made of metal and glass would be highly probable if the designer wanted to make a watch out of metal and glass and had the know-how to do so, but not otherwise. If we have no knowledge of what these goals and abilities would be, we will not be able to compare the likelihoods of the two hypotheses.

Table 1.1 Which hypothesis, Design or Chance, confers the greater probability on the observation that the watch is made of metal and glass? That depends on the abilities and desires that the putative designer would have if he existed

The question we are now considering did not stop Paley in his tracks, nor should it have done. It is not an unfathomable mystery what goals and abilities the putative designer would have if the designer is a human designer. When Paley imagined walking across the heath and finding a watch, he already knew that his fellow Englishmen are able to build artifacts out of metal and glass and are rather inclined to do so. This is why he was entitled to assert that the probability of the observations, given the hypothesis of intelligent design, is reasonably high.

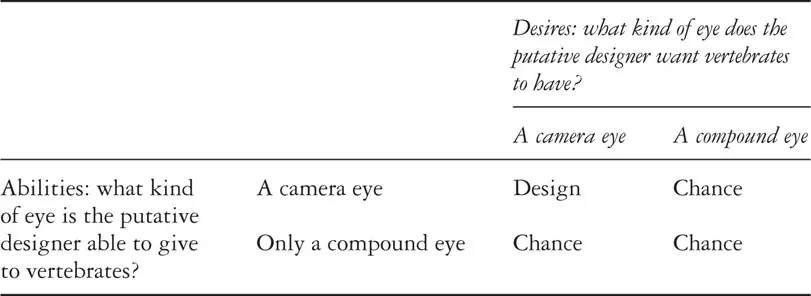

The situation with respect to the eye that vertebrates have is radically different. If an intelligent designer made this object, what is the probability that it would have the various features we observe? The probability would be extremely low if the designer in question were an eighteenth-century Englishman. But we all know that Paley had in mind a very different kind of designer. The problem is that this designer’s radical otherness put Paley in a corner from which he was unable to escape. He was in no position to say what this designer’s goals and abilities and raw materials would be, and so he was unable to assess the likelihood of the design hypothesis in this case.

The problem that Paley faced in his discussion of the eye is depicted in Table 1.2. If the putative designer were able to make the eye that vertebrates have (a “camera eye”) and wanted to do so, then Design would have a higher likelihood than Chance. But if the designer were unable to do this, or if he were able to do whatever he pleased but preferred giving vertebrates the compound eye now found in many insects, Chance would beat Design. Paley had no independent information about which row and which column is true (nor even about which are more probable and which are less).

Table 1.2 Which hypothesis, Design or Chance, confers the greater probability on the observation that vertebrates have a camera eye? That depends on the abilities and desires that the putative designer would have if he existed

Thus, Paley’s analogy between the watch and the eye is deeply misleading. In the case of the watch, we have independent knowledge of the characteristics the watch’s designer would have if the watch were, in fact, made by an intelligent designer. This is precisely what we lack in the case of the eye. It does no good simply to invent assumptions about raw materials and desires and abilities; what is needed is independent evidence about them. Paley emphasizes in Natural Theology that he intends the design argument to establish no more than the existence of an intelligent designer, and that it is a separate question what characteristics that designer actually has. His ar...